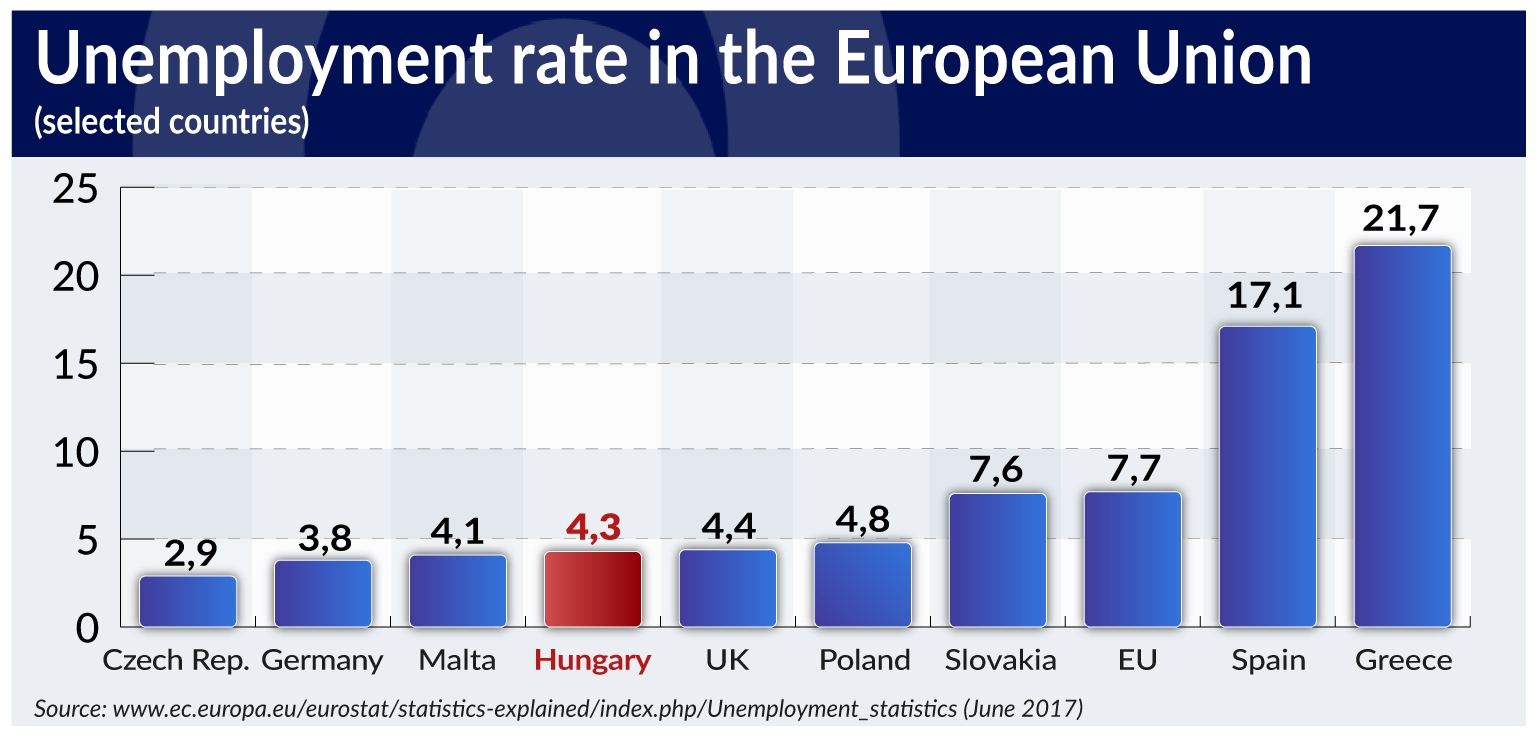

According to data from Eurostat and the Hungarian Central Statistical Office (Központi Statisztikai Hivatal, KSH) the unemployment rate in Hungary is exceptionally low and currently estimated at 4.3 per cent following the second quarter of 2017. Thanks to that, Hungary has one of the lowest unemployment rates in the European Union: the fourth lowest of all members states.

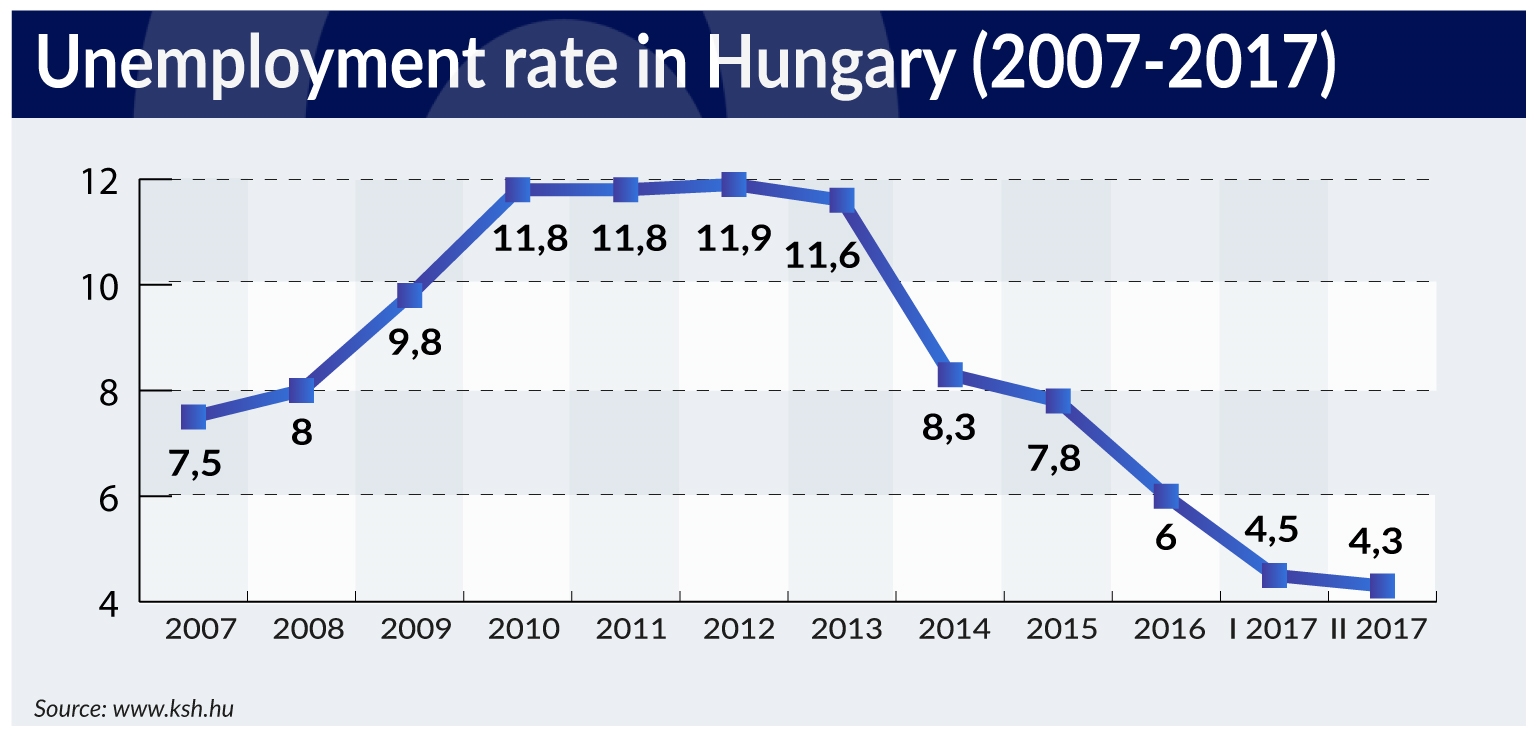

10 years ago, the unemployment rate in Hungary was at 7.5 per cent, however between 2010 and 2013 it remained above 11 per cent, and it was the highest in 2012 (11.9 per cent after the first quarter of 2012). Since 2013, it has been significantly reduced. Of the European Union countries a lower unemployment rate is currently found only in the Czech Republic (2.9 per cent), Germany (3.8 per cent), and Malta (4.1 per cent).

However, it is noteworthy to emphasize that most of Central and Eastern European member states of the EU have a lower unemployment rate than entire EU’s average (7.7 per cent). Of the other countries of the Visegrad Group Poland has an unemployment rate of 4.8 per cent, whereas Slovakia has 7.6 per cent. Only two countries in this region have higher unemployment than the EU average: Croatia (10.6 per cent) and Latvia (8.3 per cent). Perhaps unsurprisingly, the highest unemployment rates in the EU are those of Greece (21.7 per cent) and Spain (17.1 per cent).

Undoubtedly, such a decrease of the rate of unemployment in Hungary appears to be very impressive. However, it ought to be noticed that the population of Hungary has significantly declined over the last 10 years. In 2003, a year before joining the EU, it was estimated at 10.14 million, whereas in 2010 (the year when Fidesz regained power) at 10.01 million. In 2016 it was 9.82 million, meanwhile this year it is estimated at 9.78. What is more, Hungary’s population is steadily growing older. In 2000 the median age was 39, in 2010 it was 40, whereas in 2017 it is estimated at 41.6 (the source of data).

According to Hungarian Spectrum editor, Eva S. Balogh, the labor shortage is caused by the low birthrate and the massive exodus of Hungarians, which has been going on for years. In 2016 close to 30,000 people left the country.

As reported by Reuters, the annual survey by ManpowerGroup showed that 57 per cent of Hungarian companies polled had difficulties finding workers. Hungarian companies “compete for workers not just with local rivals but with employers in western European and neighboring countries as well,” ManpowerGroup’s local Managing Director Laszlo Dalanyi said. He added that Hungary’s biggest disadvantage was the lower level of wages offered to workers, which made it hard to retain or attract talented employees.

The survey said a third of Hungarian companies were unable to fill vacancies because there were no applicants at all for a given positions. Another third of employers were having problems as applicants were not sufficiently qualified, it said.

The top 10 list of problematic hiring areas ranges from blue-collar jobs such as carpenters, electricians and plumbers to drivers, engineers, doctors, information technology experts and accountants.

So Hungary will have to rely on immigrants. Balogh reminds that the government gave Samsung Magyarország, located in Jászfényszaru, a town of 5,000, permission to recruit workers from war-torn Ukraine. Of course, for Ukrainians Poland or the Czech Republic are more attractive, given the easier linguistic communication there, so Samsung had to make its job offer especially enticing. In November 2016, Samsung employed about 150 Ukrainians, and apparently their numbers are growing. In addition to their monthly pay of about HUF125,000, they receive housing, food, and travel expenses to return home once a month.

Although the economic reforms in Hungary introduced after 2010 appear to bring impressive results (reduction of the unemployment rate, stable growth of GDP, increase of salaries, etc.), the constant population outflow, particularly that of the younger generation, needs to be taken into account as well. On the one hand, the emigration evidently helped to reduce the unemployment rate, but on the other, it can cause significant problems for Hungary’s economy and social system in the future. The Hungarian government has already taken steps towards encouraging Hungarians to stay in the country and to have more children. Social benefits and subsidies for young marriages buying new flats are worthy of mention. In a couple of years, it will be possible to assess the success of these activities.

Michał Kowalczyk is a PhD student at the History and Social Science Department of the Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński University in Warsaw. He specializes in Hungarian and Central European politics.