Tydzień w gospodarce

Category: Trendy gospodarcze

(Infographics: Bogusław Rzpeczak)

There is a growing gap opening up between their state and the West as well as with an increasingly powerful China. The country’s economy has plunged into relative backwardness and hardly anything or anybody in the state works well. Meanwhile, rather than being up in arms, Russia’s citizens applaud their ruler. There is a rational explanation for this paradox, but its explanatory power is weakening.

In spring five years ago, one dollar cost 28 roubles, and in Poland ‒ PLN2.80. But then things started developing differently in both countries. If the zloty had fallen as dramatically as the rouble, today one dollar would cost PLN8 in other words, twice as much as what the dollar actually costs. As Russians say: Russia’s fiercest enemy is rising prices.

In this sad economic and political situation, Russians are being helped by their artists. “It’s somewhat tough, but happiness lies just around the corner, so rouble, just you watch yourself, don’t fall down (нo погоди, нo погоди, не упади),” sang pop star Dmitrij Malikov in a warning addressed to the rouble.

But the rouble hasn’t listened, and neither have other macroeconomic indicators. In 2015, Russia’s GDP shrank by 4 per cent, while industrial output fell by over 4 per cent. Inflation exceeded 15 per cent, and the budget deficit stood at 2.8 per cent of GDP, although it would have been much higher if inflation had not raised the state’s nominal income. Due to high yields of between 10-11 per cent, Russian Treasury bonds have become as “lucrative” as Greek, Turkish and Venezuelan bonds, and among the significant economies of the world, they are not far behind Brazil, whose 10-year bonds allowed brave investors to earn 16 per cent in 2015.

For years the Russian economy has suffered from the commodity curse, also known as the “paradox of plenty”. It is not such an acute case as Venezuela, but instead of helping the country, Russian oil, gas and the Siberian Mendeleev’s table of precious elements, is holding it back.

The result of basing the economy on commodities it that many Russians have problems mentioning even a few local products that are worth buying apart from food. A list was compiled of the top three: hunting weapons, cars exported under the Lada brand (but only when the purchase of a western car is completely impossible) and winter valonki – Russian felt boots that are perfect for a severe winter. The list could also include Kamaz trucks.

Practically all consumer durables in Russia are imported. The only enclaves of relative industrial quality are the arms and space industries, which gave birth in the 20th century to the civilian aeronautics industry, producing fuel-guzzling passenger planes – Ilyushins, Tupolevs and Yakovlevs – all uncompetitive with Western rivals.

The world’s long-standing problem with Russia and Russia’s problem with itself is the phenomenon of the “thug”. When he is in the mood, a thug can turn violent and polite society can do nothing. Russian support for the policies of their president, incomprehensible almost everywhere else, is often explained as the delight troublemakers feel over the fear they instil in their supposed betters. However, this is probably not the most important factor.

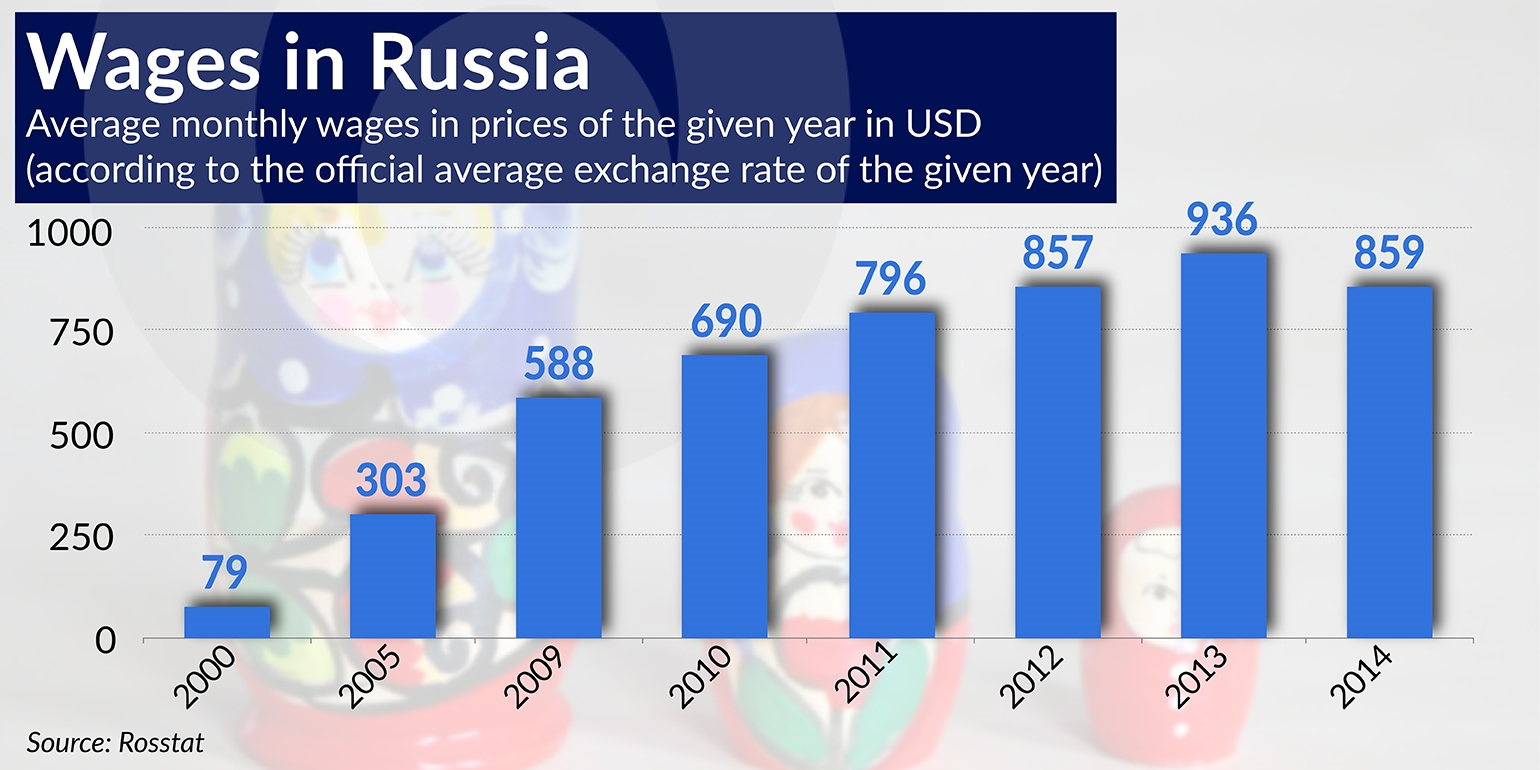

Things are bad in Russia, but relatively speaking, people are not too badly off, and certainly better off than a dozen or so years ago. According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO) as well as other sources, over 2000-2013 Russians’ real wages rose almost three-and-a-half times. A couple of years ago real wage growth stalled, but in comparison with 2000, in November 2015 they were still three times higher than at the beginning of the century.

(Infographics: Bogusław Rzpeczak)

Statistically, the latest damage to the payroll (the drop from three-and-a-half times to three times) is marked, but helped by the idea espoused by many Russians that their nation is surrounded by a hostile world, it has not caused any noticeable discontent. According to Rosstat, in 2005 there were 2,575 strikes in Russia, in which almost 85,000 people took part. In 2014, there were apparently only two strikes, with only 500 workers protesting out of 72 million employed Russians. Obviously official statistics have to be treated with caution, but it would also be difficult to hide any large waves of organized discontent, so the thesis about the positive influence of rising real wages on the mood in society is rather easy to defend.

Over the same period, gross salaries in the Polish economy rose from PLN1,924 to PLN3,900, in other words, they doubled. Therefore, if we were to assess the attitude of the average Russian, it is worth imagining how much better the mood of Polish citizens would be today if the average gross monthly wages were not around PLN4,000, but almost PLN6,000.

The figures for Poland were given as nominal figures. In reality, i.e. after adjusting for inflation, in the period 2004-2015 wage growth in enterprises was 48 per cent, and from 2010-2015 a more modest 14 per cent. Therefore, Russians had good reason to be pleased with the generosity of the Kremlin.

An important factor strengthening public support for Russian authorities is the memory of the troubles in the last decade of the previous century. If the value of Russian real wages in 1992 is set at 100, during the great financial crisis of 1997-1998 during the presidency of Boris Yeltsin, real wages were only about. Wages only recovered to 1992 levels in 2007.

Therefore, in the eyes of the average Russian, the collapse of the USSR, the governments of Boris Yeltsin and the attempts to conduct quasi-western economic reforms ended in a humiliating defeat, while the return to “tried and tested” post-Soviet methods of governing restored pride and prosperity

In the first decade of the 21st century, Russia saw a significant increase in consumption. According to the World Bank, in 2001 daily per capita consumer spending was the equivalent of USD9: By, 2010 it was almost USD17 (data in 2005 PPP USD). The number of people in absolute poverty also dropped, with those allocating no more than USD5 per day on consumption falling from 40 per cent of the population in 2001 to 10 per cent in 2010.

There was also enough money in the coffers of the state-controlled economy for other expenditures. According to the International Institute for Strategic Studies, in 2015 Russia allocated almost 5.5 per cent of GDP to the military, up from 4.5 per cent in 2014 Russian defense spending as a percentage of GDP was second only to Saudi Arabia, which spent 13 per cent of GDP on the military in 2015. Although the percentage of GDP is large, absolute defense spending is more modest. Russia spent USD66bn on the military in 2015, only USD10bn more than the United Kingdom, but not much more than a tenth of what the Americans spent (USD598bn) and less than half of what the Chinese spent (USD146bn).

The financial possibilities of the state and real wages, as well as pensions, rose in Russia thanks to the explosion in commodity prices. In December 2000, the price of Brent crude (the Russian REBCO blend is always slightly cheaper) was USD27 per barrel, at its highest peak in July 2008, it was USD145, and in recent months it has occasionally fallen below USD30 per barrel.

Russia did not take advantage of the commodity bonanza to modernize its economy. Instead, it bought itself social peace, but it lost industrial and innovative distance to the West, to China, and even to India.

The World Bank estimates that Russia’s GDP calculated in PPP USD, would be USD3,7 trillion in 2014 while in Poland it was be USD94bn, in other words, Russia’s GDP is only three times larger than Poland’s although its population is four times larger and besides coal and copper, commodities are scarce in Poland. Russia does even worse in Russia in exports, which in Poland were USD200bn in 2015, while in Russia they were only USD331bn.

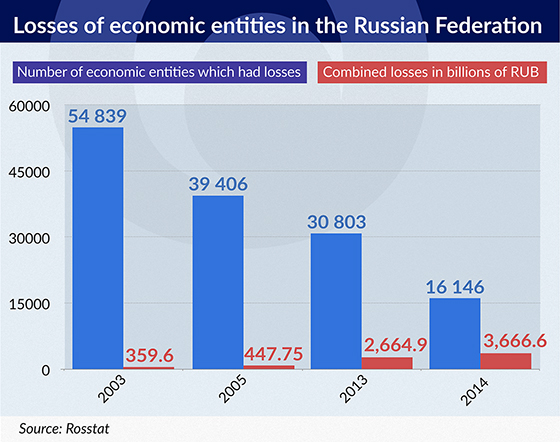

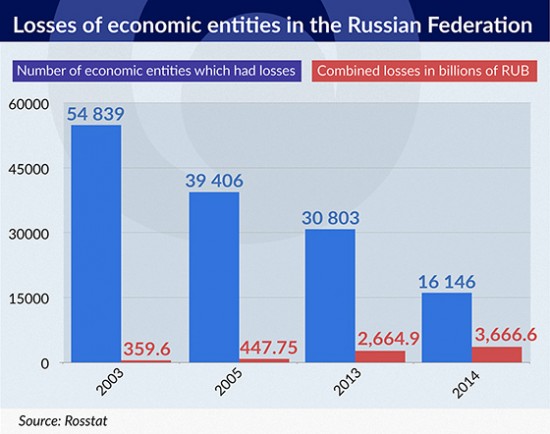

Russian companies have few examples of technological or management innovation. It is true that the number of loss-making Russian enterprises has fallen, but between 2003-2014 their combined losses rose ten times.

(Infographics: Bogusław Rzpeczak)

The outlook for the Russian economy is very poor. Money for the potential reconstruction, restructuring, modernization and construction of new industry and agriculture has instead been consumed. Rosstat said that in 2015 real wages fell by 9.5 per cent. In December 2015 one in seven Russians were living below the poverty line and the number of poor rose by over 2 million compared to 2014. Russia has lost 15 years of tantalizing its citizens with the illusion of a sustained improvement while achieving little.

Russia is huge, but it is only a , while if it had better used the era of commodity prosperity it could even have advanced to being a middleweight. From the Polish, European and global perspective, the scenario of Russia’s advance would be desirable, because a satisfied country is less likely to brawl.