The country’s record low inflation levels, stable exchange rate, growing cooperation with international financial institutions, and at the same time the growing share of the private sector in the economy, are the effects of only some of the changes introduced in Belarus in recent years.

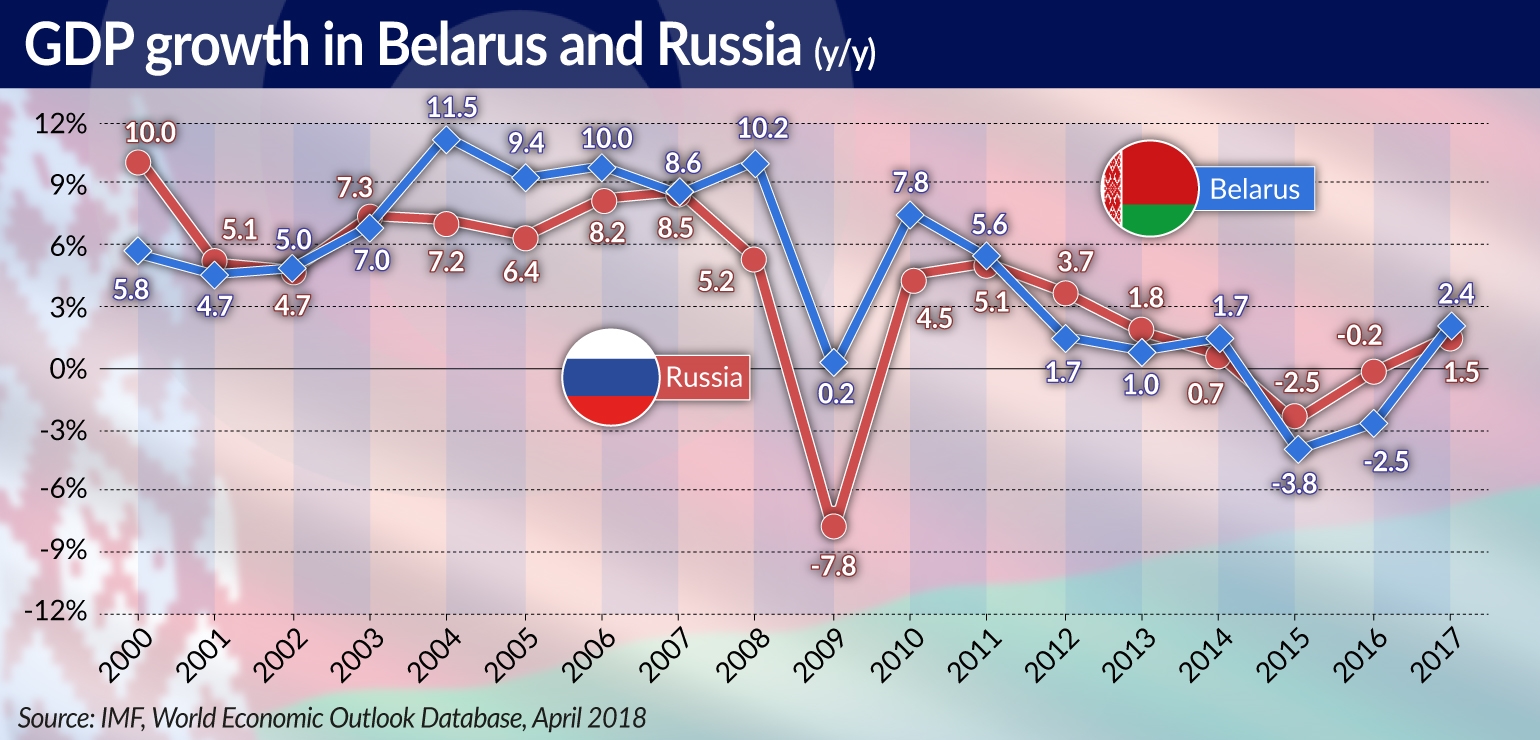

Over the past decade, the growth potential of the Belarusian economy has significantly decreased. While in the years 2000-2008 the economy was growing at a rate of 8.0 percent per year, in the years 2009-2017 it only grew at a rate of 1.4 percent. Additionally, in the years 2015-2016, Belarus has experienced its first recession since 1996. The forecasts for the future also aren’t very good. According to the international institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank (WB), the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), or the Eurasian Development Bank, in the medium term, Belarus will grow at a slower rate than the global economy, including the countries of Central and Southeast Europe (CSE). Without fundamental market reforms, Belarus may face a longer period of lagging behind the more developed countries.

The authorities in Minsk are aware that the good times for the Belarusian economy — which were the result of high energy subsidies from Russia and the fast growth of the Russian economy — are now a thing of the past. Unfortunately, a lot of time and a lot of resources had to be wasted before they came to recognize this fact. Belarus survived three economic crises: the economic slump in 2009 in response to the global crisis, the balance of payments crisis in 2011, and the currency crisis at the turn of 2014 and 2015. Additionally, during that time Belarus has accumulated a relatively high level of public debt.

Successful reforms by the central bank

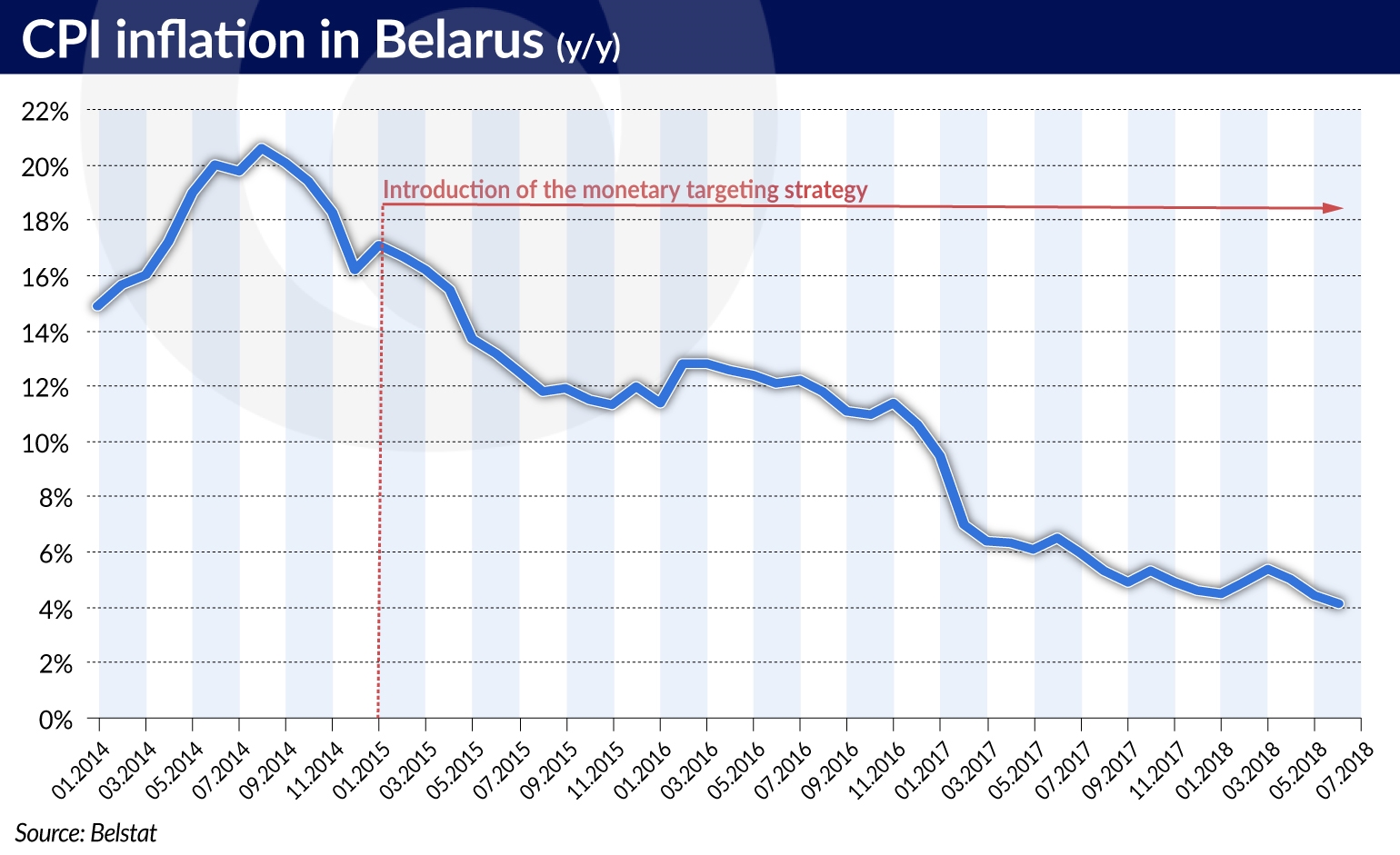

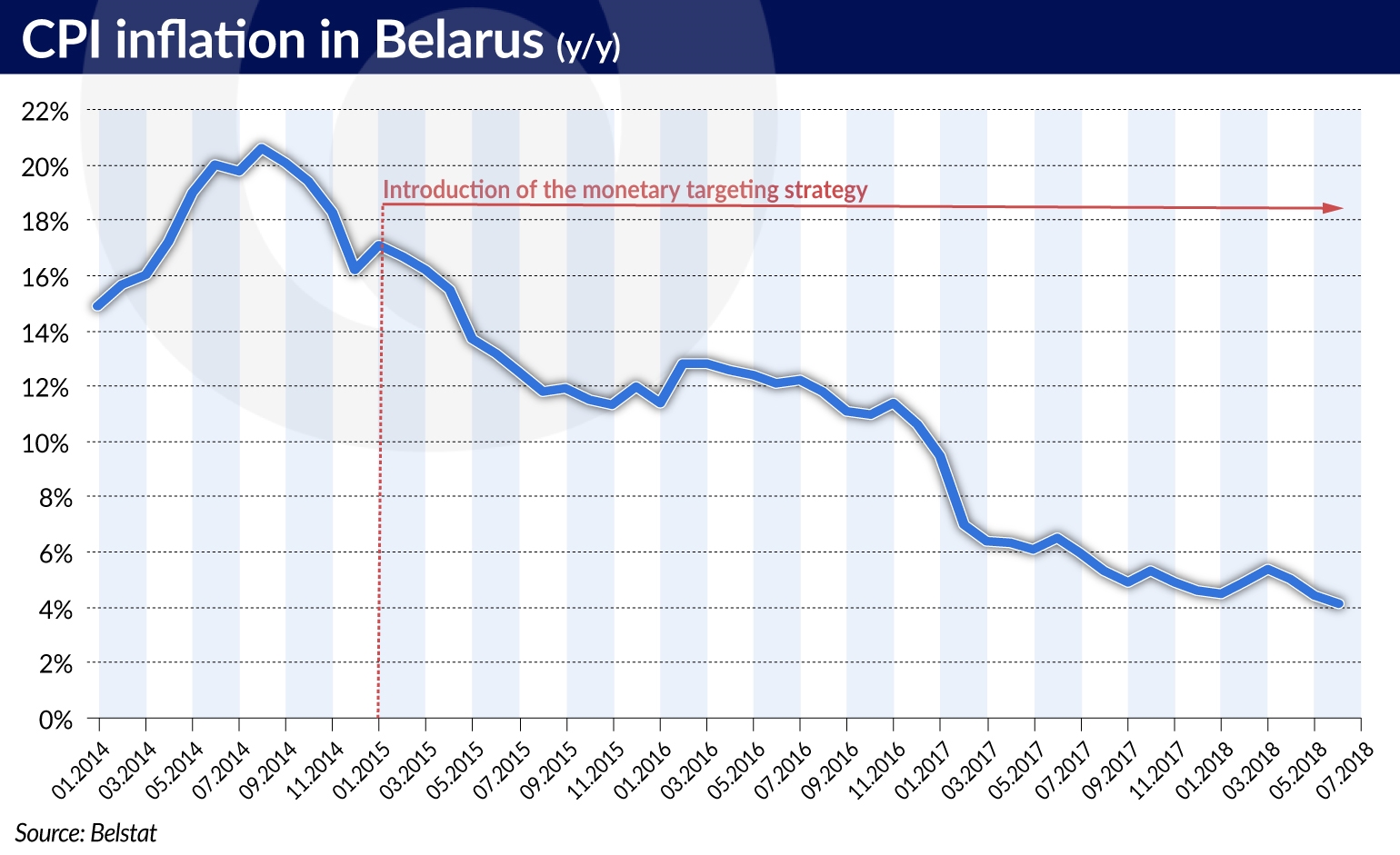

Until the end of 2014, the economic growth in Belarus was generating macroeconomic imbalances in the form of high inflation, high current account deficit and rising foreign debt. Pavel Kallaur, serving as the Chairman of the National Bank of Belarus (NBB), has become one of the pillars of the new approach to the economy, according to which macroeconomic stabilization creates the foundation for sustainable growth and gradual market reforms. During his term in office, he managed to bring inflation under control and stabilize the exchange rate. In light of a relatively high rate of price increases (18.1 per cent y/y in 2014), the strategy of monetary targeting introduced at the beginning of 2015 and the policy of high real interest rates have resulted in a gradual decline in inflation to 4.1 per cent y/y in June 2017, i.e. the lowest level historically recorded in Belarus.

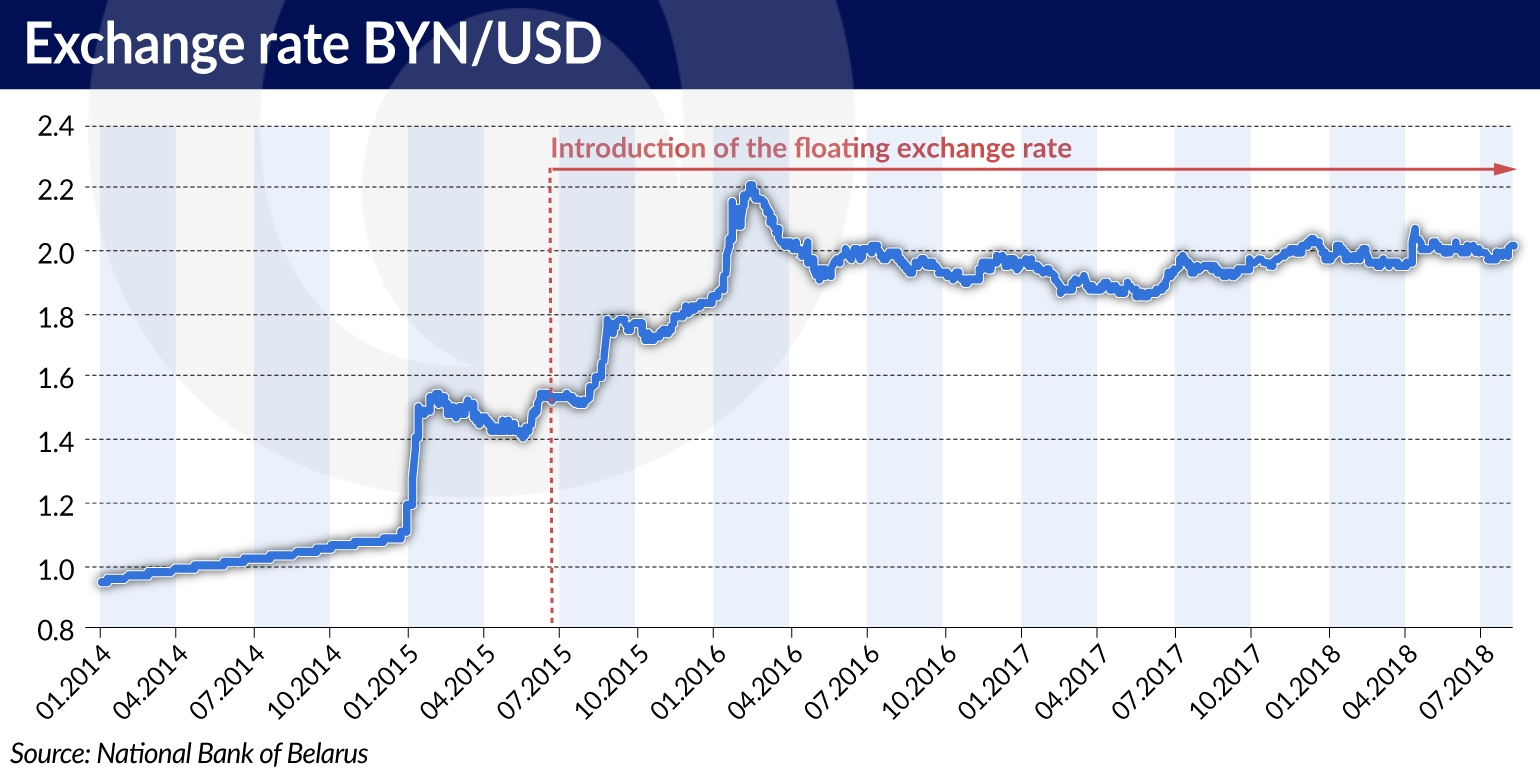

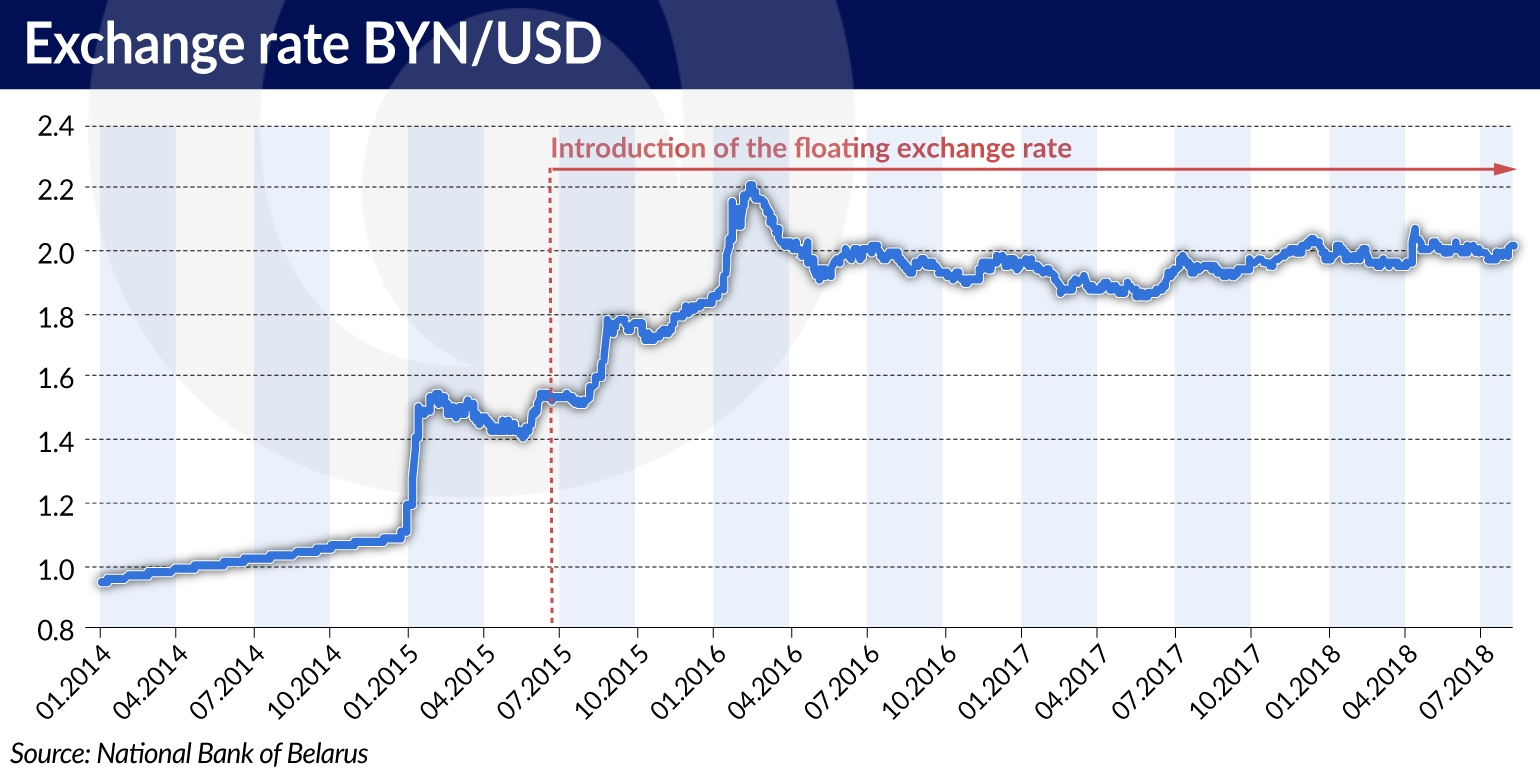

Outside of monetary tightening, the Belarus’ central bank, NBB transitioned to a floating exchange rate system. Since then, the exchange rate has been determined pursuant to transparent market principles, and the regulatory body has practically withdrawn from the market, or has at least stopped using its currency reserves to support the BYN. In reality, the NBB sometimes boys out foreign currencies from the market, in order to prevent the domestic currency from appreciating too much, which would hurt Belarusian exporters. Belarusians pretty quickly adapted to the new situation and stopped fretting about „unexpected” devaluations of the BYN. As a result, since 2015 households have been the net sellers of foreign currencies. This was the case not only during the recession, when Belarusians could maintain a stable level of consumption by selling off their foreign currency savings, but also in the years 2017-2018, after the real incomes of the population already started growing. Despite this, the faith in the Belarusian currency has its limits — in July 2018 deposits in the national currency only accounted for 30.7 per cent of all deposits of households.

Paradoxically, since the Q2’16 the exchange rate of the BYN against the USD has been more stable and predictable than in the days of the fixed exchange rate.

It is even more stable than in the other countries of the region, including Poland. This has made it easier for the NBB to take further steps on the way to the liberalization of its exchange rate policy:

- The obligation of enterprises to sell 30 per cent of their foreign currency income on a regulated currency market was gradually abolished in the years 2016-2018.

- The banks’ obligation to register the passport data of natural persons purchasing foreign currency was abolished in June 2017. This rule was introduced back in October 2011 during the currency crisis in Belarus.

- The restrictions pursuant to which enterprises could only acquire foreign currency for specific purposes (for example, to service foreign currency debt) were abolished in January 2018. Before that, companies could not buy currencies on the foreign exchange market, and the NBB had been making decisions in this respect since the 1990s.

The change in monetary policy should be treated as a structural change for the Belarusian economy, because the exchange rate finally started to fulfill the role of an automatic stabilizer of external and internal shocks. As a result, the current account deficit (mainly resulting from the trade deficit) decreased from -6.7 per cent of the GDP in 2014 to -1.7 per cent of the GDP in 2017. This has been the second best result since 2000.

Additionally, the central bank has placed emphasis on transparency in the conduct of its information policy, which is conducive to building confidence in the national currency. In the past several years the conservative forecasts and promises of the NBB have actually been coming true, which strengthened the bank’s authority. According to the NBB’s Governor, the bank may implement a direct inflation targeting strategy by the end of 2020.

Balanced fiscal policy

The financing shortage has forced the Belarusian government to improve budgetary discipline, among other things, by:

- gradually withdrawing from new preferential loans for state-owned enterprises;

- limiting the rate of wage increase in the public sector to the rate of labor productivity increase;

- optimizing employment in state-owned enterprises and public administration;

- raising the retirement age by 3 years for men and women;

- reducing the state funding for housing construction;

- imposing a tax on freeloaders (the „social parasites tax”), which has been suspended eventually.

The above-mentioned activities have negatively affected the social contracts between the authorities and the citizens in recent years.

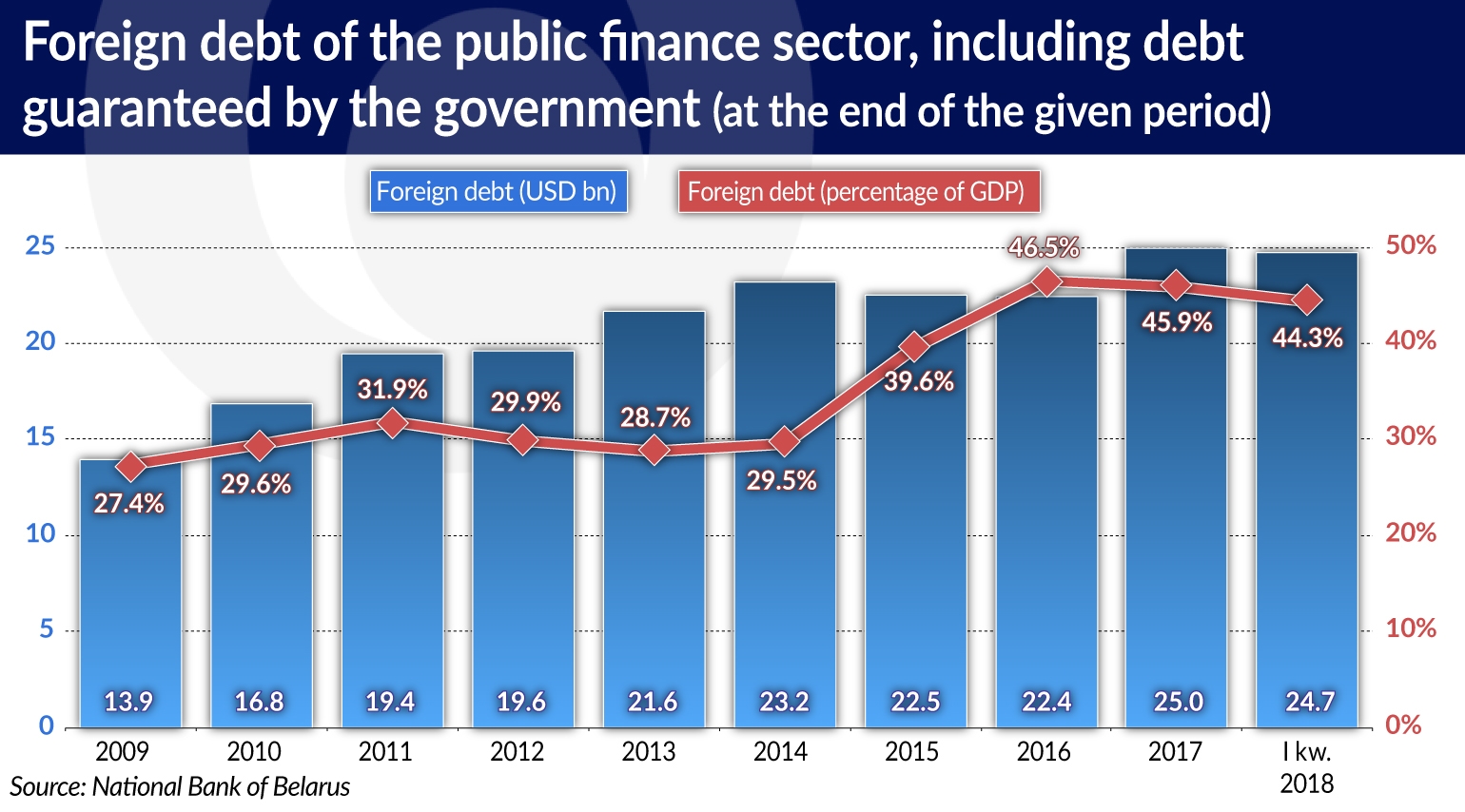

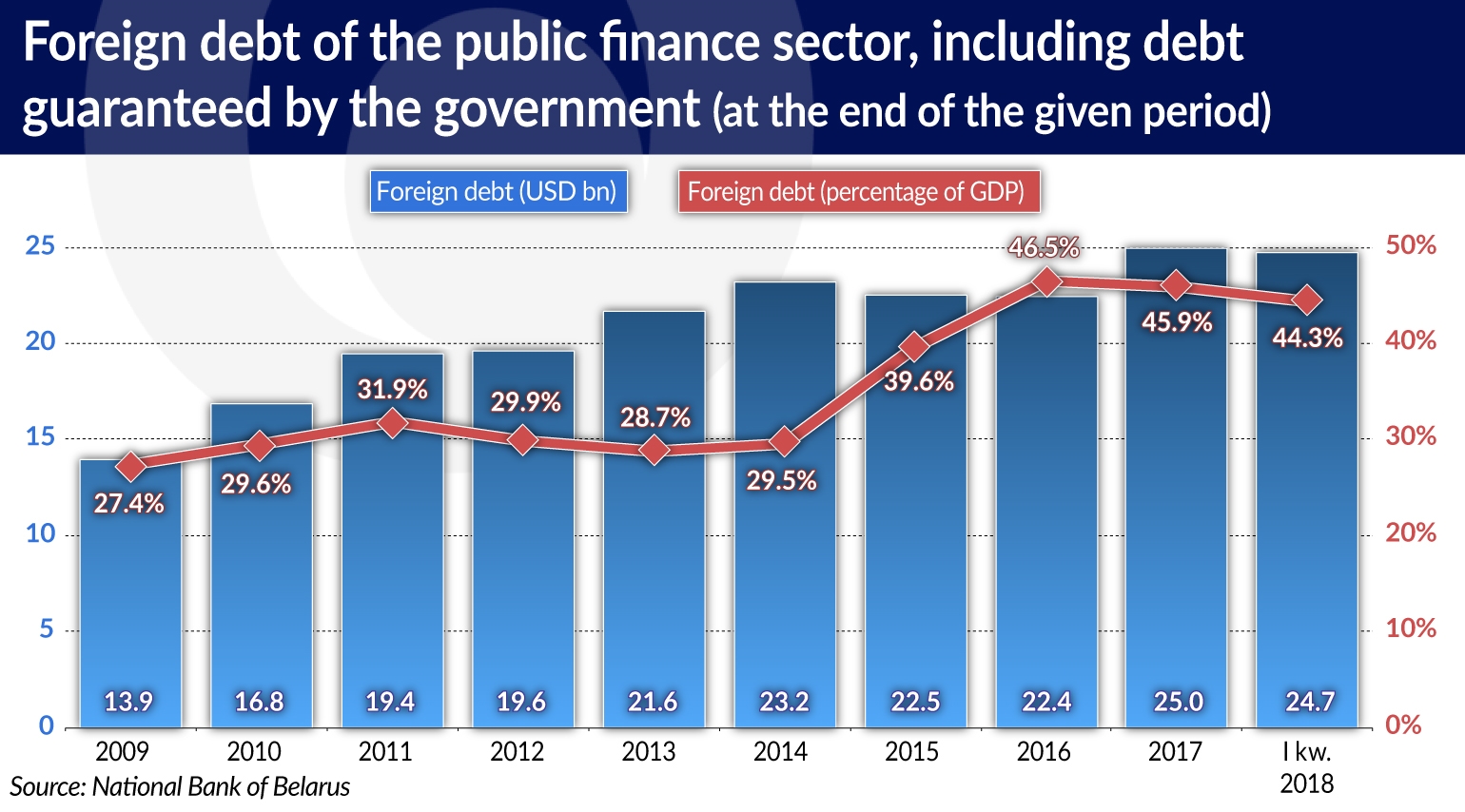

Over the past few years, the Belarusian authorities have become aware of the problem posed by the high level of public debt, which is mainly denominated in foreign currencies and which has been rapidly growing until 2014. The hopes that foreign loans (mainly from Russia and China, but also Eurobonds) would enable Belarus to modernize its industrial champions, create new and effective enterprises and survive the tough times, have proved futile. Meanwhile, the servicing of the public debt has gotten increasingly expensive. For example, since 2013, the debt servicing expenses (payment of interest and repayment of the principal) have amounted to over USD3bn per year, including USD3.6bn (approx. 6 per cent of the GDP) in 2018. These costs will remain at a similar level of about USD3.5-4bn in the years 2019-2023.

The problem of debt is not being swept under the rug, as was the case in Greece. Since 2014, Belarus has maintained a primary budget surplus (a primary balance is the difference between the state budget’s incomes and expenditures, excluding the debt servicing costs — editor’s note) of approx. 1-2 per cent of the GDP, which is being allocated for debt servicing (read more). This represents a fundamental change in the country’s fiscal policy compared to the years 2007-2013. Back then, due to the rising prices of Russian energy raw materials, the authorities were financing economic growth with foreign loans.

At present, foreign liabilities account for three quarters of the state public debt, and are worthy of particular attention. On April 2018, the foreign debt of the public finance sector (including debt guaranteed by the government) amounted to USD24.7bn, or 44 per cent of the GDP. In absolute terms the debt only increased by USD1.3bn, i.e. by 5.5 per cent compared to July 2014. However, the debt-to-GDP ratio grew significantly in the years 2015-2016, as a result of a recession and the devaluation of the Belarusian currency. A slight improvement has only been visible in the last year and a half. Together with the domestic debt, the total debt of the public finance sector amounted to approximately USD31bn, i.e. 55 per cent of the GDP. Although this level of debt in relation to GDP is comparable to other countries, the debt servicing costs incurred by Belarus are much higher, because it is an unreformed economy with low credit ratings.

Natural change in the structure of the economy

Over the past few years, in Belarusian reality, it has been necessary to distinguish the populist messages of President Alexander Lukashenko, from the activities actually carried out by the government and by the central bank. Although there is a broad consensus among the most important policy makers as to the necessity of maintaining macroeconomic stability and introducing market reforms, there is no agreement regarding the scope and pace of implementation of these policies. Because of that, while reforms are introduced in some areas, they are suspended in other areas, and may even be reversed at times. As a result, despite very long negotiations with the IMF, the government was not able to sign the agreement for a USD3bn loan supporting structural reforms. The IMF withdrew from the negotiations due to the lack of political agreement to the implementation of reforms seen by the Fund as necessary.

Among the Belarusian elite there is no political consensus on privatization. The authorities do not want to sell the large companies. A small-scale privatization could come into play, including the sale of inefficiently used assets of state-owned enterprises. The alternative option is the sale of minority stakes in state-owned champions, because then the authorities would not lose control over these companies. Both options are considered by the state, provided that a good offer comes along. There are very few such offers, however, mainly due to the high requirements set before potential investors (such as maintaining the current level of employment).

Nonetheless, the ownership structure of the Belarusian economy is slowly changing. According to the World Bank’s survey from 2018, the productivity of private enterprises in Belarus is 40 per cent higher than that of state-owned enterprises. The increase in labor productivity in the private sector is also four times faster than in the public sector. On the other hand, although this happens very rarely, the most unprofitable state-owned enterprises are sometimes liquidated or optimized. As a result, the private sector’s share in the national economy increases in a natural way, even in the absence of a large-scale privatization program. Whereas at the time of collapse of the Soviet Union, the private sector in Belarus only produced 5 per cent of the GDP, according to the World Bank it currently accounts for approximately half of the Belarusian economy.

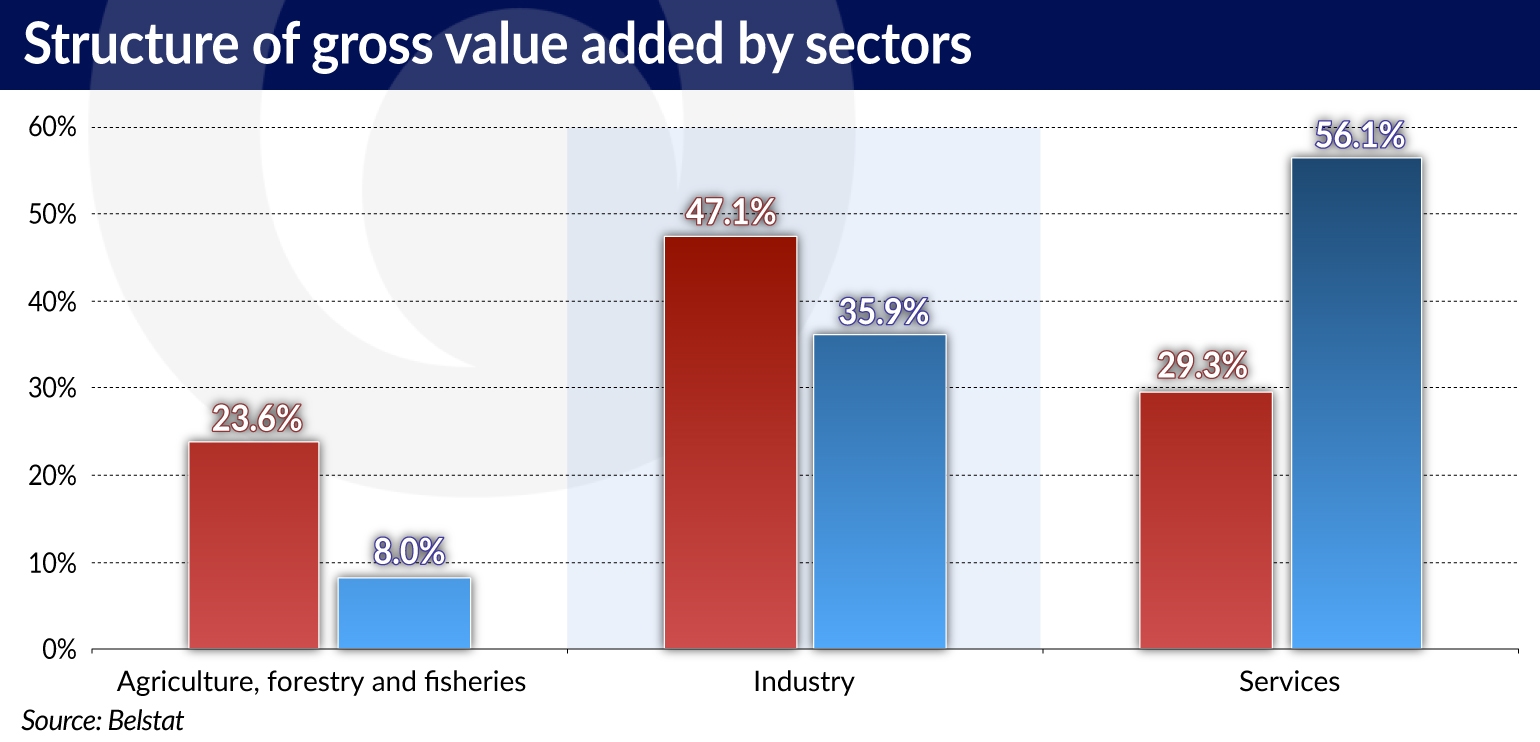

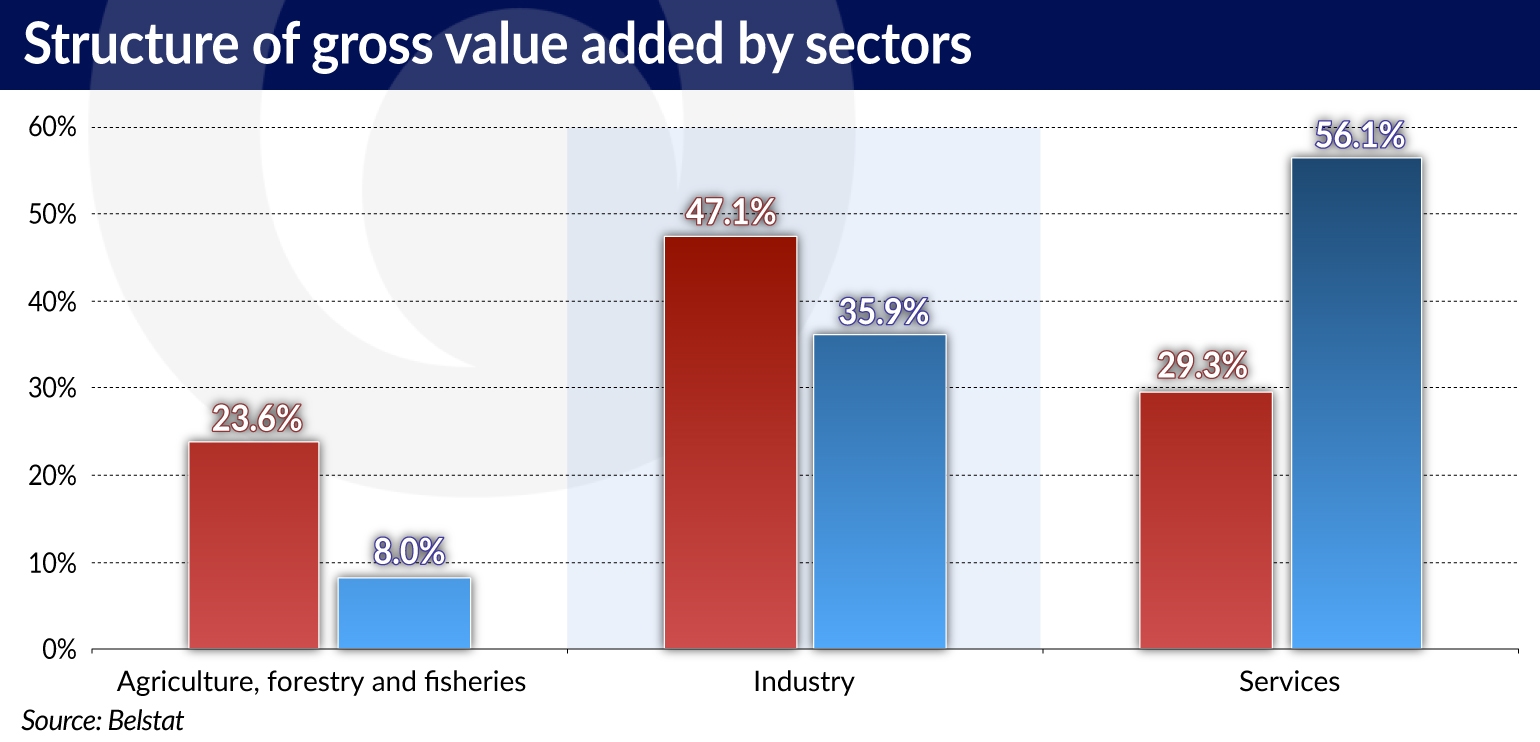

The sectoral structure of the Belarusian economy is naturally changing. The service sector is beginning to play an increasingly important role, while the importance of the agricultural sector is falling. In 1990 the least efficient sectors — agriculture, forestry and fisheries — generated 23.6 per cent of the value added, and in 2016 their contribution was already three times lower and only amounted to 8 per cent. Meanwhile, the share of the most efficient services sector has almost doubled during this period — from 29.3 per cent to 56.1 per cent.

Is there a light at the end of a long tunnel?

Whether it wants to or not, since 2015 Belarus has still been implementing some of the reforms that the IMF had originally insisted on. These reforms have been introduced without the financial assistance of the IMF itself, but have involved consultations with the Fund, as well as the expert support and/or financial support from the World Bank, the EBRD, the European Investment Bank, the European Commission and the Eurasian Development Bank. One example of such reforms is the process of eliminating the practice of so-called cross-subsidization, where the population does not pay the full cost of municipal utilities, whose costs are then passed on to the real sector of the economy. This reform has been implemented gradually, starting from 2016.

The scale of international institutions’ involvement in projects in Belarus (e.g. infrastructure, energy, SME sector) has been growing in the last four years. On the one hand, this is the result of the geopolitical situation — Belarus has been rewarded for remaining neutral in the Russian-Ukrainian conflict and has received some of the development aid which had to be redirected from the Russian economy to other economies of the region, due to the sanctions imposed on Russia. On the other hand, there is clear interest in strengthening such cooperation on the part of Belarus. Minsk has never had such good relations with the international financial institutions.

The most important question for Belarus is whether the authorities are ready to engage in more active management of the structural changes in the economy. The previous success achieved in some areas (such as ensuring macroeconomic stability) may encourage the authorities to continue its sensible economic policies and to accelerate the market reforms.

Aleś Alachnovič is the vice president of the research foundation CASE Belarus, a doctoral student at the Warsaw School of Economics and a graduate of the London School of Economics.