In contrast to the other provisions of the post-crisis banking reforms, it is difficult to say whether these solutions will prove to be effective. It would be better if there was no need to test them in practice.

It is already known that the Polish act – just like the EU’s BRR and DGS directives on which it was modeled – has many gaps that can be easily exploited by bank owners. It is also known that the banking sector could bear huge costs in order to ensure security – not only for itself but also for the taxpayers’ money. This will certainly affect its profitability.

The Polish act on the Bank Guarantee Fund, the system of deposit guarantees and forced restructuring, in force since October 10th, 2016, has not been prepared in haste. It was developed over the course of three years amid huge resistance and legal discussions, as it contains solutions not previously used in the Polish law.

“All the instruments are a novelty for us, even though they have been used in various parts of the world”, said President of the Bank Guarantee Fund Zdzisław Sokal during the Banking Summit in October 2016.

Despite this, both the bankers and the regulators agree that this is a ground-breaking and good legislation. “There is nothing but benefits associated with the new process. The use of market measures increases the market discipline. We are trying to organize insolvency in such a way that the systemic consequences are minimal”, said Olga Szczepańska, the Director of NBP’s Financial Stability Department.

“Resolution constitutes an important logical element complementing the new architecture of the banking system and a message to the public that the banking system is safe. One very important thing is that banks will not be rescued with taxpayers’ money”, said Mieczysław Groszek, the Vice President of the Polish Bank Association, during the Allerhand Institute Congress.

In the public interest

Resolution, that is, orderly liquidation, or – as this process is called in the Polish act – forced restructuring of banks, was invented after the governments of many countries in Europe incurred massive expenditures on bailing out banks. The mechanism is supposed to eliminate the moral hazard. Moral hazard is based on the fact that the States guarantee the deposits. If a bank takes excessive risk, driven by the desire for profits, goes too far and fails, the tab is ultimately picked up by the taxpayers.

The weakness of the new legislation, not only in Poland, is that it is not able to fully guarantee that the taxpayers will never again bear the costs of rescuing banks or paying the guaranteed deposits. On the other hand, in certain cases, it also fails to guarantee the availability of the funds necessary to carry out the procedure.

The Polish law strongly emphasizes that the basic procedure, when a bank is insolvent, is a regular bankruptcy. “Resolution takes place when a bank is in danger of bankruptcy, there are no positive effects of the recovery activities, and the criterion of public interest has to be met”, said Zdzisław Sokal.

What is the definition of public interest, cited by similar legislation around the world? It may be invoked if a regular bankruptcy of a bank could jeopardize the financial system stability. If there is a risk that it could lead to the insolvency of other banks. Public interest would also occur if a greater involvement of public funds was required in the case of an ordinary bankruptcy.

It is also in the public interest for a bank to continue the performance of “critical functions” (such as, for example, participation in payment systems or the fulfillment of obligations arising from exposure towards other banks). If the bank ceased to perform them, then people, other banks or the economy as a whole could suffer. The public interest would also occur if the safety of the depositors’ funds was at risk (for example, if there was no money for their payment). After the so-called public interest test is passed, a decision is made on the resolution procedure, instead of a regular bankruptcy.

Scenarios of a bank’s death

The decision on the launch of a resolution procedure is taken by the Bank Guarantee Fund, but a request for the procedure is submitted by the supervisory authority, if it determines that its actions cannot achieve the desired results in light of the bank’s situation. This means that the possibilities of implementation of the recovery program and all the instruments of the so-called early intervention, which are available to the supervisory authority, have been exhausted. At that point the decision is made. “If liquidation through bankruptcy is implausible or impracticable, then we enter the resolution procedure”, said Zdzisław Sokal.

Preparing plans for bankruptcy in advance is crucial to making the right decision. They should be prepared by the Bank Guarantee Fund, although in many countries – for example in the US – such plans are prepared by the banks themselves, and in addition, at least for the time being, only the most systemically important institutions have to prepare them. Supervisory institutions (in the United States these are the Federal Reserve and the FDIC fund, which secures deposits) assess the plans’ feasibility, consistency and – send them back to be corrected. The Bank Guarantee Fund has to prepare resolution plans for all Polish banks – 35 commercial banks and over 550 cooperative ones. “This is a huge challenge”, remarked Zdzisław Sokal.

The plans are to be developed within one year from the Act’s entry into force and they require the banks to provide the Bank Guarantee Fund with huge amounts of data which they did not provide in the previously existing reporting systems.

“It will be necessary to provide a much larger set of information than what is required for the purposes of due diligence. We will provide regular information to the Bank Guarantee Fund. Three months is not enough time, but once the system is implemented, the information will flow”, Joao Bras Jorge, the CEO of Bank Millennium, said during the Banking Summit.

Estimating the costs of bankruptcy

This data is not only required for the preparation of scenarios of bankruptcy of each bank but also for the quick estimation of the value of their assets and liabilities. This estimation, which begins the resolution process, determines the most important decisions, including the selection of the method in which the procedure is implemented, i.e. the resolution instruments. The determination of how much funds can the shareholders and creditors of the bank recover also depends on this estimation.

Such estimation should provide answers to some other questions. Is the bank actually in danger of bankruptcy and what cash flows can be expected after the application of specific solutions? Is it possible to implement the existing resolution plan, what size of possible support is required and what will be its sources?

The estimation should be performed by an external company, but in an extraordinary situation the Bank Guarantee Fund may decide on the basis of its own initial estimate, which then has to be verified by an independent institution.

The estimation of the value of assets and liabilities is associated with several risks. The first of them is illustrated by an example from the recent history. Although the crisis had already been mounting for months, on September 12th, 2008 the liquidity in the markets and the prices of many assets were completely different from those recorded on September 15th, when the Lehman Brothers filed a request for bankruptcy protection against creditors in a New York court. The valuation from September 12th would be entirely different than the one prepared after the memorable weekend.

However, the estimation must be performed on the basis of current market data. Therefore we have to hope that the initiation of the resolution process will not cause a shock on the market. That could call into question the credibility of both the promise made to the creditors and shareholders, and – which is also possible – the adequacy of the selected instruments for the conducted bankruptcy.

“The price of assets is different in the liquid and non-liquid markets. I wonder if any expert will be able to recognize whether the valuation is correct”, said Piotr Bednarski from PwC during the Allerhand Institute Congress.

The decision on the initiation of the resolution process is irreversible. It may not be revoked even by a court decision. The situation is entirely different when it comes to claims against the liquidator – and this is a weakness not only of the Polish legislation, but also of the entire European legislation. So this is the second risk involved. The shareholders and creditors may not only challenge the valuations but may also try to prove that as a result of the decision on the resolution procedure they have suffered losses much greater than they would in the case of a regular bankruptcy. And if they prove that then they will be eligible for compensation. Financed by the taxpayers.

“The European resolution agency (Single Resolution Board) hires huge law firms in order to ensure the legal handling of these processes, because there will be disputes with those who incurred losses on the write-offs. It is likely that the (Polish) courts will be burdened with the cost of hiring the best law firms (in order to verify the estimates, in the event of disputes)”, added Piotr Bednarski.

Resolution instruments

The law provides the Bank Guarantee Fund with several options for dealing with a failing bank. The simplest solution is its sale – in whole or in parts – to another institution interested in an acquisition. In such a situation, funds are needed for the rebuilding of the capital of the failing bank or assistance to the acquiring bank, so that its capital is not affected. Such assistance requires the consent of the European Commission and is only possible if 8 per cent of the bank’s capital or its liabilities are first written off in order to cover the losses. The assistance in the financing the acquisition cannot be provided by the Polish central bank, NBP, although it may grant a loan to the Bank Guarantee Fund, should the payment of guaranteed deposits be at risk.

In spite of the appetite for the purchase of subsequent banks manifested by the biggest Polish insurance company, PZU, on the Polish market there are not many entities willing to take over such institutions. This method is therefore limited by the demand for banks which can be even lower in times of crisis. “There don’t seem to be very strong tendencies for the acquisition of some institutions by others”, said Andrzej Stopczyński, a Director at the Bank Guarantee Fund.

The second tool, which is seen as a temporary solution, is the creation of a bridge bank. It will probably be selected when no one is willing to acquire a bank, either due to the complexity of the institution or the lack of an obvious balance of risk, when it is necessary to apply a more discerning distribution of the assets and liabilities of the failed bank. The bridge bank is to perform the same functions as the failed one – to conduct all operations with the partners, to receive and pay deposits, etc.

The law stipulates that NBP may provide liquidity to the bridge bank on the same principles as it does to any other bank, that is, only when it is confident that the bank is solvent.

New funds

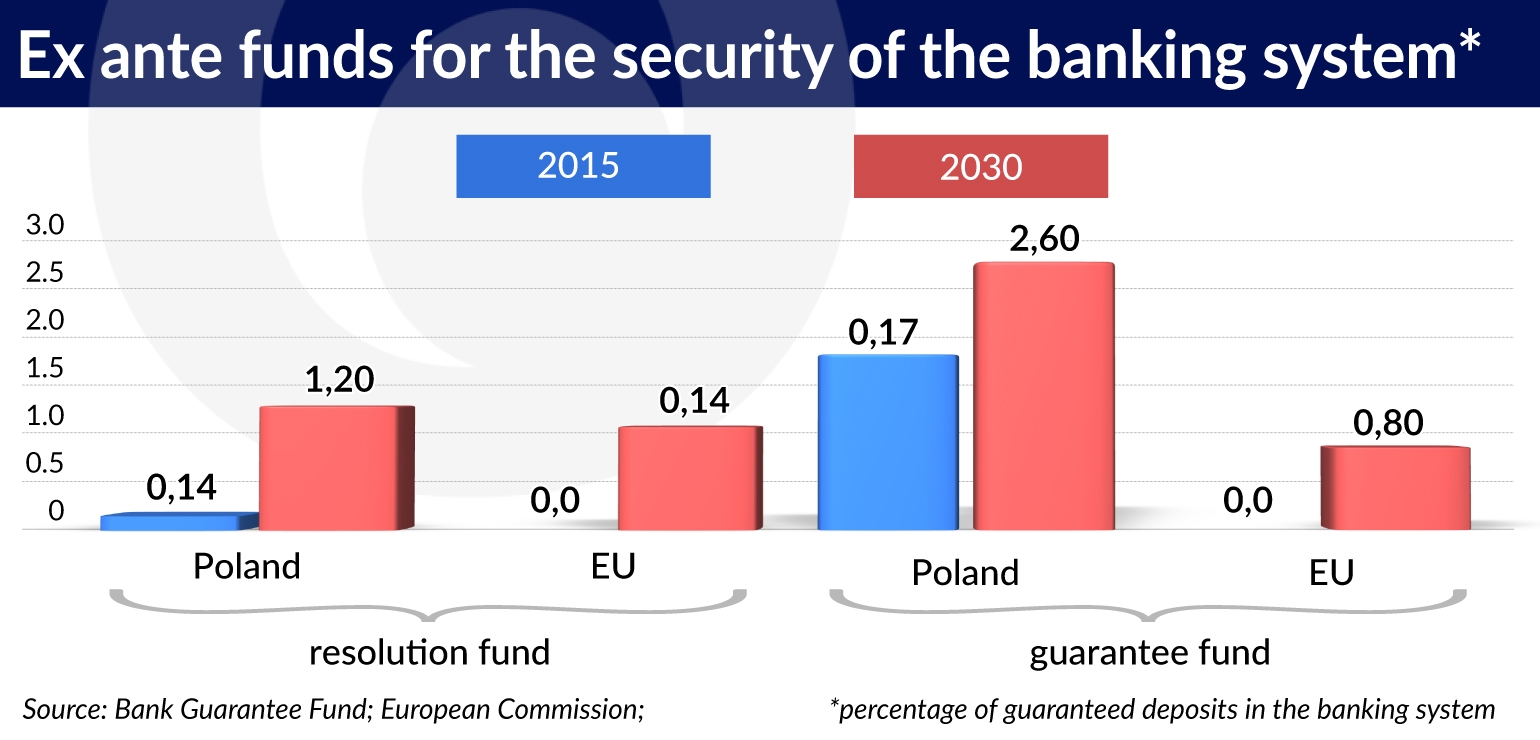

The banks will have to contribute resources towards the payment of guaranteed deposits and the fund supporting the resolution procedure. The former fund is expected to amount to 2.6 per cent of the guaranteed deposits held by Polish banks, and the latter is expected to amount to 1.2 percent of their value. Both funds are to be “filled” by 2030. This is six years later than in the European Union and that it was initially proposed. However, the funds will be relatively higher, because in the European Union in 2024 the resolution fund is to amount to 1 per cent and the deposit guarantee fund is supposed to amount to only 0.8 per cent.

The method of calculating contributions will change significantly, because larger banks and those with a greater risk (calculated according to a very complex methodology which takes many factors into account) will pay more. Small banks, including cooperative banks, will probably pay much less than in the past.

“The contribution will depend on the overall assessment of the bank’s risk, including the assessment of risk exposure, the stability of financing sources, the importance of the institution in the system and additional risk factors, such as the exposure to derivatives, the scale of the necessary support, as well as liquidity”, said Zdzisław Sokal.

The deadlines for the payment of the contributions will also change. Their amount for the next year is to be determined by the Council of the Bank Guarantee Fund by March 1st, 2017 and the Bank Guarantee Fund is to notify banks by May 1st, 2017. Banks will pay the contributions in the second half of 2017.

How much will they now have to effectively pay to the Bank Guarantee Fund? Experts confirm that the amount paid into the resolution fund could reach PLN0.8-1bn per year. According to the annual report of the Bank Guarantee Fund for 2015, the stabilization fund, which will support the resolution fund, already contains 0.14 per cent of the guaranteed deposits, and in addition to that, the Bank Guarantee Fund has already gathered 1.7 per cent of ex ante funds for the guarantee of deposits. This means that approx. 1 per cent of the amount of guaranteed deposits is missing in both funds.

Bail-in and MREL

Another possibility, after covering the losses with capital, is the exchange of the bank’s liabilities for capital, that is, a bail-in. It is an instrument which is supposed to ensure that losses will not be passed on to the taxpayers. Regulators have come to the conclusion that in many cases a minimum capital requirement of 8 per cent may not be enough for covering losses, and let alone the rebuilding of capital.

That is why an instrument known as MREL (the minimum requirement for own funds and eligible liabilities) was invented. Every bank that can be subjected to resolution will need to have bail-inable liabilities, or MREL, used for covering losses if the capital was insufficient, and also for the rebuilding of capital. As a last resort, however, losses can be covered using almost all of the remaining obligations of the bank with the exception of guaranteed deposits.

“In an extreme situation, there is the possibility of writing off deposits above EUR100,000”, said Zdzisław Sokal. “We don’t want to assume that bail-in is the preferred solution”, added Andrzej Stopczyński.

However, MREL may be used not only when a bail-in is applied but also when a bank is taken over, or for the equity of a bridge bank. Its amount is the topic of ongoing discussions in the European Banking Authority (EBA). It is known that for small institutions, which will simply be liquidated – and this would be the case for the majority of cooperative banks – MREL may only reach the amount of the capital requirement.

“The amount of MREL will depend on the assessment of the supervisory authorities. Banks (in Poland) have high own funds and apply their own models to a small extent, which – in the context of low-leverage business activity and the good condition of the economy – gives more flexibility while determining MREL level. MREL should be set at a lower rather than a higher level”, said Deputy Chairman of the Polish Financial Supervision Authority Wojciech Kwaśniak during the Banking Summit.

In the case of large banks MREL will probably be twice as high as the capital requirement, and in the case of the largest banks – twice as high as the capital requirement along with buffers. It will be much lower for small banks.

“For cooperative banks it will be a requirement at the maximum level of 1.5 times the capital requirement”, said Vice President of the Bank Guarantee Fund Krzysztof Broda at the Forum of Leaders of Cooperative Banks.

The banks’ problem with MREL is that few of them have qualified liabilities, for example in the form of subordinated debt, as they are mainly financed with the use of deposits. And in some institutions such obligations should account for up to 30 per cent of equity. Anyway, they are preparing for the issue of instruments with a relatively high level of risk, which means that banks will have to pay a lot for the acquisition of MREL.