It is not clear whether these objectives can be reconciled. The new directive could mean that Polish banks will be less secure.

In order to understand the intentions behind the Directive we have to take a look at the situation of the banking sector in Europe which is in some respects vastly different from the Polish one. The fact that a transfer ordered in the morning is credited to the payee’s account in the afternoon is not an obvious thing in other European countries. In some, it can even take up to several days to pass through.

For the banks quick payments are a cost, because they need to build and integrate appropriate electronic systems. Polish banks have already borne these costs and are still doing that by developing mobile banking, whereas after the credit crunch many other financial institutions in Europe are not able to bear them.

At the same time, until recently, the level of fees for the implementation of payments, including interchange fees, has been encouraging many larger and smaller technology companies to become involved in the circulation of money. Various business models were created, whose goal is to provide more convenient, faster and cheaper services to the customer. It’s about acquiring a larger scale, coverage, and customer loyalty and – which is as important – acquiring information provided by the customers themselves while paying electronically.

The most important, however, is the development of e-commerce and mobile payments. Purchases made in a traditional store have one major advantage over purchases made on the internet – we see the goods, we can touch them. Then we can pay and the product is ours.

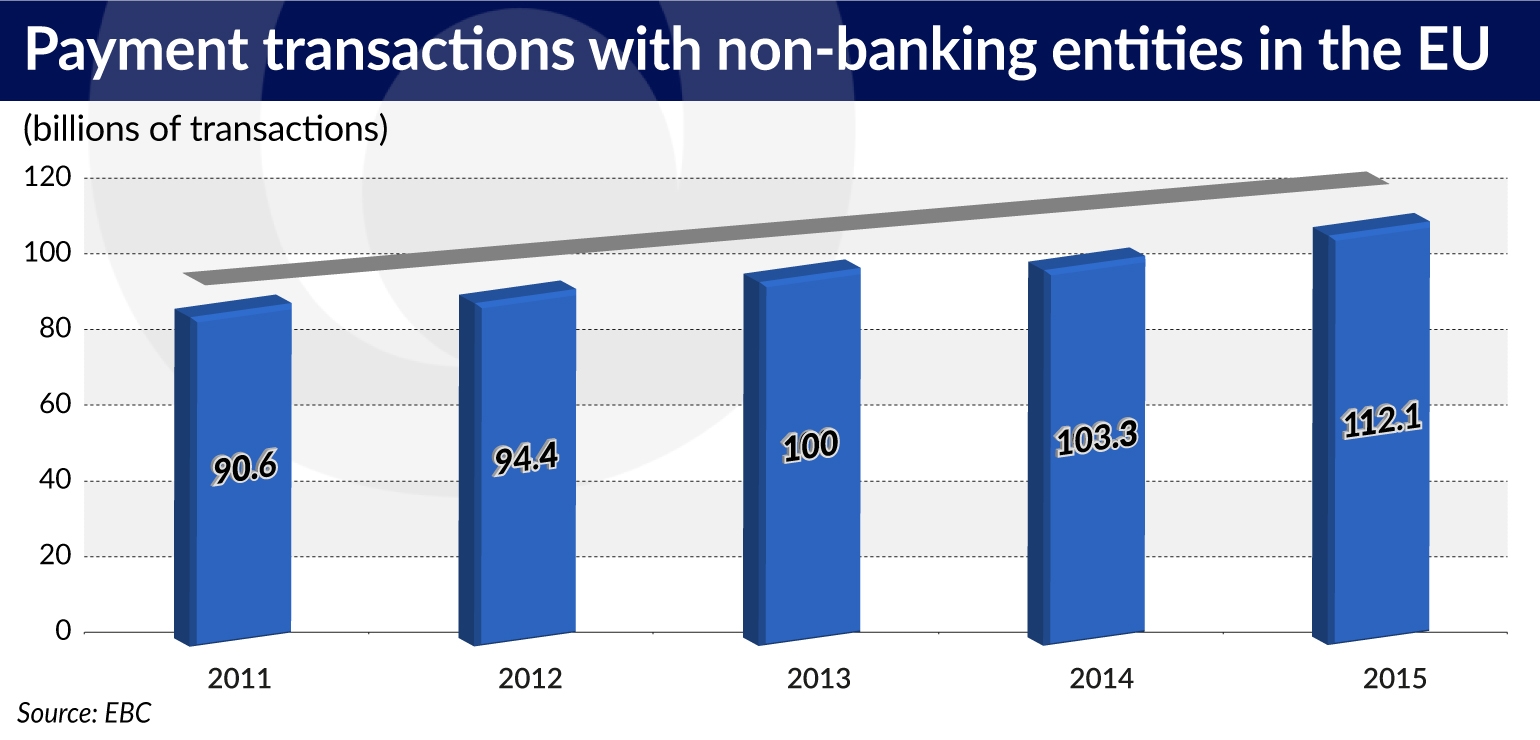

In Poland, banks and stores have developed the pay-by-link method, which, according to data from PayU, is used by 80 per cent of customers paying online. The transfer is immediately posted and the goods can be sent. But if the transfer to the account takes ages instead of happening in a flash an intermediary is required in its implementation. According to the data of the European Central Bank by the end of last year there were over 8,000 non-banking institutions involved in payment services in the European Union.

The idea behind mobile payments is that the transaction should be carried out immediately, from any place and at any time. This has led to the current competition – the goals include speed, ease of use, the conversion rate, that is, the percentage of accepted transactions and positive customer experience. The way to gain advantage in this race is the introduction of new technologies, and the PSD 2 is supposed to support that.

The key importance of the Regulatory Technical Standards (RTS)

The PSD 2 directive entered into force in January 2016, and has to be introduced into the national laws in January 2018. The most important thing, however, is not the Directive itself, but the Regulatory Technical Standards (RTS), which are to be ultimately issued by the European Banking Authority (EBA). These standards will assign appropriate weight to the priorities.

Payment security is to be ensured by the principle of strong authentication. The PSD 2 is not the first act aiming to introduce this solution. Already in 2012 the ECB issued recommendations concerning internet payment security. Some national supervision authorities have implemented them, others not. The banking supervision in Poland has taken the most consistent course and issued an appropriate recommendation. Because not everyone followed ECB’s recommendations, the European Commission wanted to ensure the establishment of hard regulations in place of soft recommendations.

The European Banking Authority, which is to prepare the RTS, i.e. a crucial interpretation of the Directive, has already consulted the draft standards twice. The first consultative round was held immediately after the adoption of the Directive in 2015, when the European Banking Authority presented its preliminary position. The second round of consultations ended in October and the European Banking Authority is expected to announce the RTS in their final form soon.

In order for the RTS to take effect it is necessary for the European Commission to approve them at the latest in April 2017. In this way they would enter into force after 18 months, that is, by the end of 2019. This is assuming that there are no delays, as the discussion on the matter is extremely heated. Over 200 opinions packed with arguments were sent to the consultations. The banks are defending their position which they built thanks to the exclusive knowledge of the accounts of their customers. New players are looking to undermine their positions, and in this way conquer the territory still controlled by the banks.

Competition has many names

The EBA has put an emphasis on introducing strong competition to the market of payments. Because a significant percentage of European banks are not able to provide swift execution of transactions for their customers, new players have to be allowed on the market to the greatest extent possible. These are the so-called third party providers (TPP), who will be able to access the customer’s account on their behalf through a special interface intended for this purpose, known as the API, which will be open to all third parties. The banks will be obliged to create such an interface.

“In the RTS we can see a lot of emphasis on convenience and competitiveness,” said Tomasz Piwowarski, a director in the Polish Financial Supervision Authority.

A key issue remains: if the TPP has access to the customer’s account, then what will be the extent and the principles for that access? The representatives of the Polish supervision authorities and the banking sector agree that the standards implemented in Poland are optimal, because they combine high requirements concerning safety, ensure competitiveness and motivate towards technological competition.

“We are concerned that through the introduction of new services, the entry of players whose standards may be different from ours, these lower standards could penetrate our market under the guise of PSD 2,” added Piwowarski.

The introduction of the obligation for the banks to „issue” an API has – in addition to opening the market to competition – one more important side effect. Thus far each TPP that wanted to carry out payment transactions on behalf of a customer had to negotiate and conclude an agreement with the bank. Such an agreement included, i.a., the rules concerning the distribution of responsibility for the customer’s money in the event of fraud.

After PSD 2 enters into force each TPP will be able to „connect” to the bank’s API without the obligation to conclude any agreement. And at the same time the directive states clearly that the responsibility for the customer’s money lies with the bank. This means that in the event of fraud due to the fault of the TPP, the bank will have to return the money to the customer, and only then attempt to prove that the TPP should return the money to the bank. This puts the banks in a situation much more difficult than before.

“After the introduction of the PSD 2 there will be no contractual principles between the TPP and the institutions running the accounts. This may cause tension,” said Maciej Biniek, a member of the management board of the payment service provider PayU.

Why is there so much pressure from PIS (payment initiation services) and AIS (account information services) to allow the customer to share their data? Because it’s a way to offer them their products.

“Having access to the history of payments, we can precisely assess the customer’s situation. The bank sees the history of the account and can assess the customer. When this advantage ends, competition will increase”, said Mariusz Cholewa, the president of the Credit Information Bureau.

Banks often cite their concern about the security of the customers but at the same time they are fighting not to be forced to share their information about the customers, even if the customers themselves wish that. In this way they block their competitors from entering the market.

“The main threat to the banks is the decline of their role as the owners of the information about the customers,” said Dariusz Szkaradek, a partner at Deloitte.

The weak points of strong authentication

In order to ensure payment security, PSD 2 introduces the principle of strong customer authentication (SCA), which has been used in Poland for many years anyway. All service providers will have to apply the principle of strong authorization. This will include both the Account Servicing Payment Service Provider (ASPSP), as well the PIS (payment initiation services) and the AIS (account information services).

The principle of strong authentication involves the identification of the customer on the basis of at least two of the three possible categories – knowledge proprietary only to that customer, exclusive possession of something and some individual characteristic. These are the personalized security credentials (PSC), in the banking language known simply as „the credentials”.

And so the category of exclusive knowledge is matched by the password we use to log in, known only to the customer, the category of possession – is fulfilled by a one-time code sent by the bank to confirm the given transaction, and the category of individual characteristics – is met by biometric features, e.g. a thumb print. Strong authentication is supposed to ensure that its elements are independent of each other, and thus a breach of one of them does not call into question the credibility of the others. It is supposed to be constructed in such a way as to protect the confidentiality of the authentication data.

There are a few exemptions from strong authentication. One of them, known as „dynamic linking”, concerns a situation where we send money to a defined recipient or where we send a previously defined amount. There are also exemptions for small transaction amounts.

The vast majority of banks participating in the consultations of the European Banking Authority is of the opinion that it should not present a detailed list of exemptions, and leave this to the risk analysis carried out by the market participants. The same proposals were presented by the European Financial Congress after consultations with the Polish banking community. Meanwhile, companies providing payment services have expressed their strong support for a precise and limited list of exemptions.

The growing volume of electronic payments is accompanied by rise in cybercrime. Criminals are looking for the weakest links in the various systems and exploit these weaknesses to steal money. Therefore theoretically strong authentication should reduce the chance of a successful attack and the extortion of funds.

It is already clear that this is not the case, and that strong authentication does not provide complete protection, as criminals apply increasingly effective methods of stealing the authenticating data, that is, the credentials. The key issue here is who has access to them. The RTS draft allows for the bank customer to make their credentials available to another entity that is supposed to provide services for them. And this is the issue that generates serious concerns as to whether the standards ensure sufficient security.

It is not certain whether the non-banking institutions will be able to protect customer data so well as the banks do. At least in Poland the banks have made really impressive progress in the protection of sensitive data. The authentication of identity by the bank may become the primary way to access the services of the public administration through the so-called Trusted Profile.

“If this data is provided to small companies, which do not necessarily have adequate protection systems, then things may get a bit scary”, said Mariusz Cholewa. “If we break the principle that only the client and the bank have access to the account, then we break all the principles. This would have huge negative implications for the digital world,” he added.

“The credentials should remain secret. The technical standards are not clear enough to confirm this,” said Piotr Alicki, the chairman of the National Clearing House.

The dark sides of screen scraping

In Poland there is a rule that no matter who is the initiator of the payment or who intermediates in it, the transaction itself is authorized only by the customer in the bank’s transaction system. No broker has access to the customer’s password or the login, nor the code authenticating the transaction, which is sent by the bank, regardless of the system or technology in which it is implemented.

“We have solutions that have been functioning successfully for many years. I would like to preserve the status quo of the Polish market, because it provides confidence and has resulted in good systemic solutions,” said Feliks Szyszkowiak, a member of the management board of BZ WBK.

Meanwhile, in many EU countries the system of screen scraping has become popular. Several Polish lending institutions began to use it but the Polish Financial Supervision Authority quickly prohibited it. Screen scraping is when customers make their credentials available to another bank (or a PIS) and agree for their accounts to be used on their behalf and within the entrusted scope. In Poland this involved retrieving data from the customer’s account, for example during the presentation of a loan refinancing offer.

“Methods analogous to screen scraping are responsible for more than half of the criminal attempts,” said Piotr Alicki.

It looks like the RTS are going to legitimize the use of a very dangerous tool. If it is validated, the bank will not be able to tell whether it is used by someone who performs a service for the customer, or by someone who is stealing money.

Contrary to the intention behind the directive, i.e. for the payment service providers to offer the most simple and most user-friendly solutions, the draft proposal of the RTS, if it was implemented in its present form, could hamper the development of mobile payments. The European Banking Authority believes that it is necessary to separate the channel through which the customer communicates with the bank, from the one through which he receives the code to confirm the transaction.

What does that mean? When we are on our desktop computer and make a transfer order in the online banking service we receive a code to authorize the transaction, usually by SMS (some banks are still using scratch cards). These are the two separate channels – connection through the computer browser and a telecommunications connection.

Things are different, however, when we are using a mobile app. We use it to connect to the bank, and to place the transfer order, and at the same time, we receive the authentication code on the same device. Experts combating cybercrime believe that using one device for both of these steps significantly increases the likelihood of success for cyber criminals. But if the standards were introduced in their current shape, the ease of use of telephone payments would be significantly reduced.

Meanwhile in the mobile payments market the goal is to ensure that the consumer is able to pay with the least number of steps. So that he doesn’t even have to enter a six-digit code. Contactless cards define the standard of ease and convenience that all payment operators are seeking.

The European Financial Congress suggested that the principles of separation of channels might be softened depending on the risk management policy of the payment providers, and that less restrictive principles of strong authentication might be allowed in the case of one-click payments and recurring payments. It believes that it is necessary to introduce the principle of logical device authorization, which would confirm that it is assigned to a particular person.

The Polish Financial Supervision Authority wants the European Banking Authority to leave at least some of the decisions on safety rules on a particular market to the national authorities.

“Sharing the account data – yes. But the credentials have to stay within the bank’s infrastructure,” said Tomasz Piwowarski. “We are able to develop an approach concerning access to the account, which is safe and does not undermine the confidence in the banking sector,” he added.