Tydzień w gospodarce

Category: Trendy gospodarcze

(deargdoom57, CC BY)

(infographics: Darek Gąszczyk)

According to the definition, digital competences are the set of skills necessary for the effective use of electronic media. They include both the skills of operating computer equipment and software, using different applications (the so-called IT competences) and the ability to search for required information in various — electronic and traditional — sources, in order to process and use it accordingly to needs (information competences). However, they also include the creative use of the possibilities offered by digital media, the ability to communicate and build relations through, for example, social media (building self-image), and to ensure safety. Digital competences also comprise a certain knowledge of the legal framework and mechanisms of media economics.

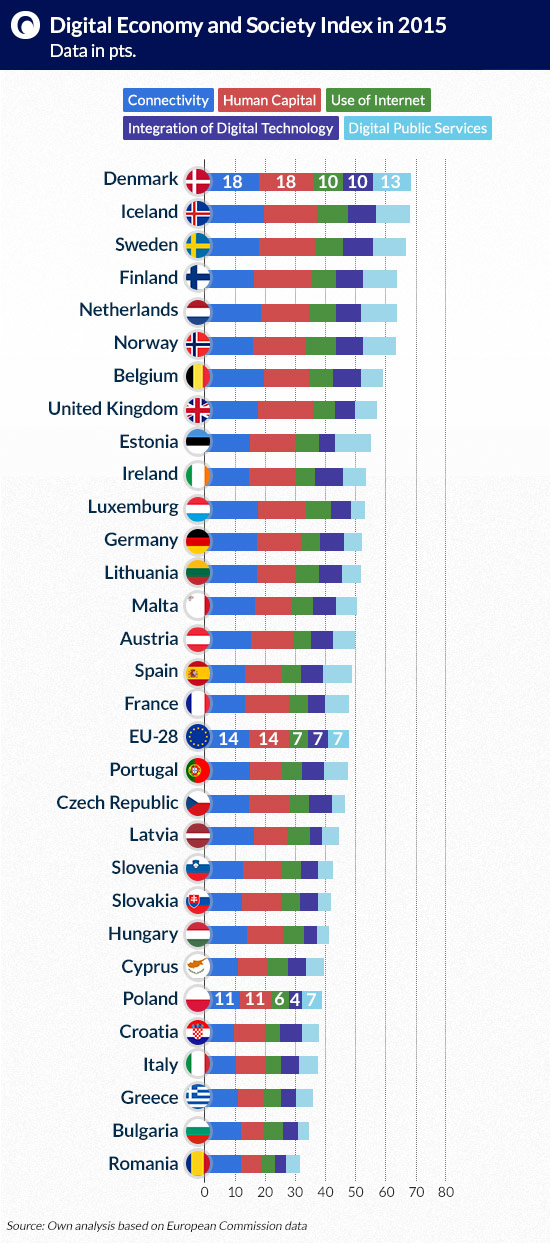

The answer is fairly simple: rather not. Poland ranks 24th among the 30 European countries surveyed by the European Commission in terms of the development of a digital economy and society (Digital Economy and Society Index). The most digitally advanced countries are Denmark, Iceland, Sweden, Finland, the Netherlands and Norway. The least developed ones —starting with the lowest ranking position — are Romania, Bulgaria, Greece, Italy and Croatia. Poland is not among the five lowest ranking countries but it is preceded by, among others, Hungary, Slovakia, the Czech Republic and all the Baltic states (Estonia was even ranked 9th in Europe).

(infographics: Darek Gąszczyk)

As regards human capital development associated with digital economy, Poland is doing slightly better, as it is 23rd in the ranking. The leader, not only in terms of IT specialists, but also in terms of people with advanced computer skills, is Finland, followed by Sweden, Denmark and the United Kingdom. Romanians, Bulgarians, Greeks and Italians are the worst performers.

Poland holds 27th place in the EU in the use of new technologies in business (B2B) —CRM systems, cloud computing and storage, and e-commerce. The Nordic countries are again at the top of the ranking in terms of integration of digital technology with business, and the last place in Europe is occupied by Latvia (just after Romania). Poland performed best in the index of development and use of digital public services by the modern media. In this respect Poland is 16th in the EU, ahead of such countries as Italy, Germany, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Luxemburg. Denmark is the leader, closely followed by Estonia, while the Netherlands rank third.

Where do Poles learn to use computers and the internet? Mostly from their own experience. The study published by the Warsaw Institute for Economic Studies shows that 79 per cent of Poles learnt to operate the computer by themselves, 5 per cent were taught by their parents and 17 per cent by their elder siblings. The data on the use of the internet look slightly different — 62 per cent of respondents were self-taught, 5 per cent were introduced to the internet by their parents, 12 per cent were assisted by their brother or sister, 19 per cent were assisted by their friends and a mere 2 per cent learnt to use the Internet from their IT teacher.

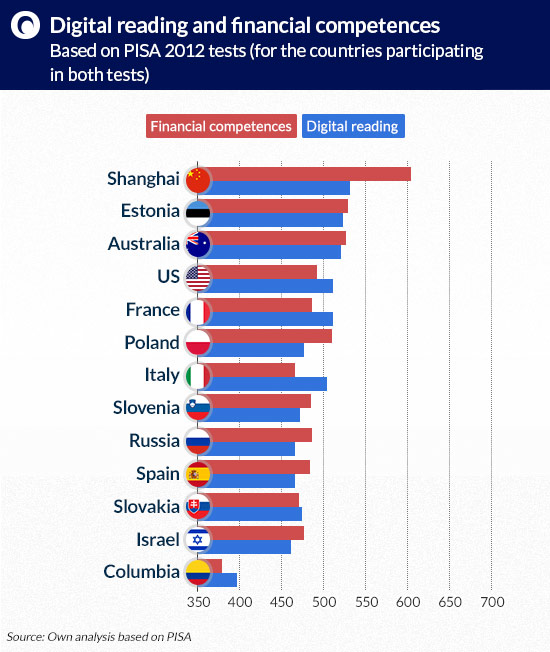

Every few years the OECD examines the skills of 15-year-olds in the developed countries, not only in the area of reading comprehension but also solving mathematical and scientific problems (Programme for International Student Assessment, PISA). The last two rounds of the study included digital reading tests, assessing the use of hypertext and the ability to search it for information. Young Poles did not perform in these competence fields so well as in the analogue test, in which they are the world’s leaders. The average score of 477 pts. gives Polish students 22nd place among the 32 surveyed countries. They were outscored by Americans (12th place, while they more often perform worse than Poles at maths, for example) and Estonians (7th place). The world’s best performers were Koreans and Singaporeans. Interestingly enough, Poles outdid young Israelis (27th place) at digital reading.

The conviction that young Poles download homework and papers from the internet does not necessarily mean that they do it quickly. When looking for information, our middle schoolers waste as much time browsing unnecessary sites and links as students in other countries do (14 per cent). In the OECD countries, on average 13 per cent of time needed for task fulfilment is used ineffectively. In Estonia the proportion is 15 per cent, and in Columbia and Spain it exceeds 20 per cent. It is worth noting, however, that students in Shanghai or in Germany manage to reduce this time to just 8 per cent, and in the US — to 10 per cent. Searching for information in the net is a skill that also needs to be improved in Poland.

Digital competences are the result of an economy-oriented education system, which we lack. Students in Estonia scored 523 pts. in digital reading and 529 pts. in the financial competence test, consisting of solving practical economic problems, e.g. drafting a family budget. Australia, Belgium, the US and France had similar scores. Young people from Poland do better at solving economic problems than at digital test. Only Russia and Spain, countries which cannot boast of best labour markets in the world, are facing a similar situation.

(infographics: Darek Gąszczyk)

Excel is not taught at university

71 per cent of Poles with a higher education diploma admit that they can do basis arithmetic calculations in Excel. This is more or less the European average (73 per cent). A similar proportion of people who can do one of the key operations in the present labour market are in Norway, Great Britain, Austria, Spain, Sweden, Greece and Denmark. Among Czechs the figure is 78 per cent, and in Iceland and Slovenia it reaches almost 90 percent. The lowest number of university graduates skilful at using spreadsheet program are in Romania (52 per cent), Bulgaria, Hungary, Italy and Croatia.

It should be no surprise that Poland was the country where the greatest number of events in Europe were organized on the European Code Day — over one and a half thousand, because only one in twenty Poles had any programming experience. It is slightly better among university graduates. 12 per cent of Poles holding a diploma have ever written a computer programme or a fragment of a code (a result similar to those recorded in the Czech Republic, Bulgaria, Romania and Hungary, as well as Estonia and Denmark). The percentage of people with such experience is the highest in Finland (36 per cent), Sweden (31 per cent) and Iceland (30 per cent). On average, such advanced computer operation was performed by 19 per cent of Europeans with a higher education diploma.

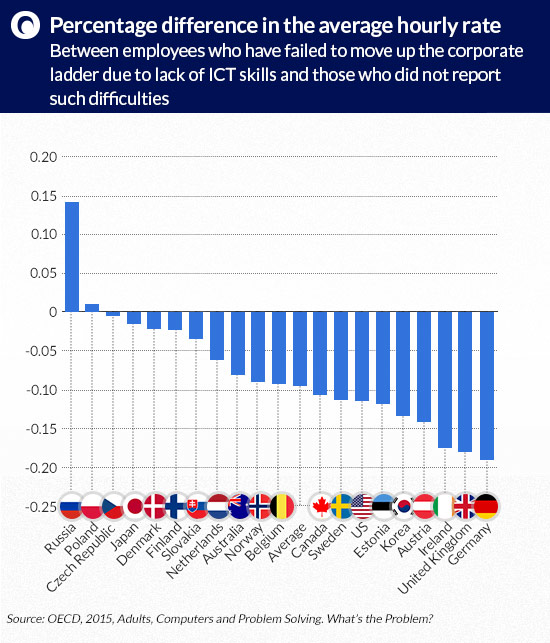

In Poland, mastering advanced computer skills does not translate into higher remuneration. In nearly all the OECD countries, especially in Germany and the United Kingdom, employees who lack sufficient computers and internet skills usually fail to climb the corporate ladder and earn less. The only exception is Poland, and outside the OECD — Russia (see the graph below). In any other country, anyone who is not familiar with Microsoft Word will not get promotion.

(infographics: Darek Gąszczyk)

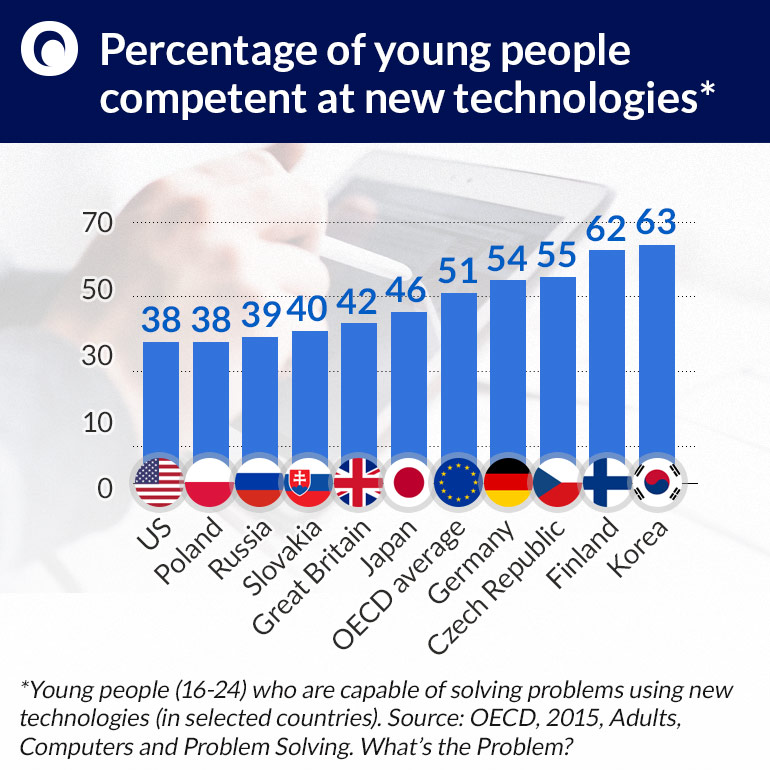

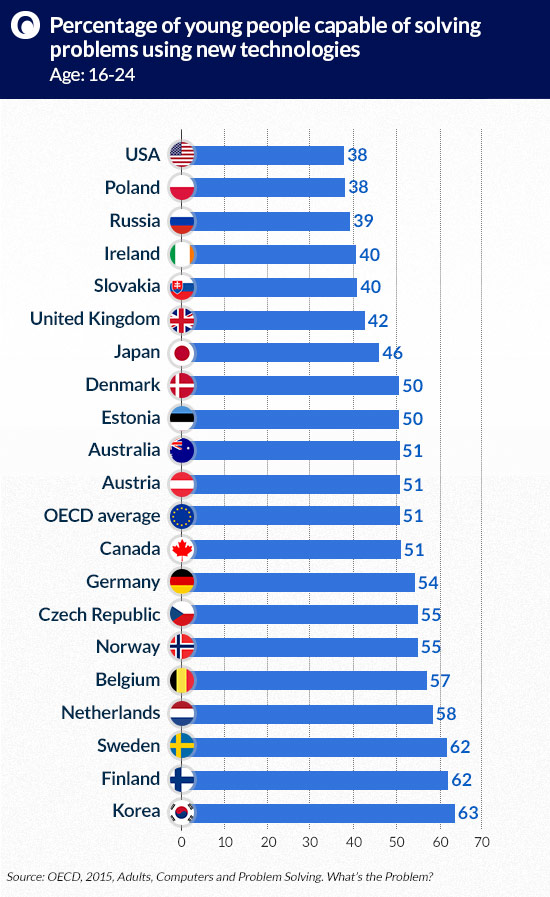

Worse still, young employees in Poland are unable to cope with problem solving by means of computers. When asked by their boss or teacher to prepare, for example, a presentation, a mere 38 per cent of Poles aged 16-24 will cope with the task. Similar computer illiteracy rates are recorded in America and Russia – in all the other OECD countries illiteracy rates are considerably higher. We can say that computers alone do not teach, but in the countries where new technologies are used, teachers can do a much better job.

(infographics: Darek Gąszczyk)

Poland faces an economically significant problem of a shortage of adequately skilled workforce. As we know, old professions will cease to exist — there will no longer be simple farmers or labourers. The Polish assembly workshop will have to turn into a workshop of new technologies. Polish vocational schools seem to be unprepared for the task, since young people leaving our educational system cannot cope with these tasks and, what is worse, graduates from Polish schools cannot cope with them either.

Aware of the problem, employment offices should approach training courses for the unemployed in a completely different way. They should send the unemployed to programming schools instead of flower arrangement courses. In every job present in 10 or 15 years’ time, it will be critical to be able to write at least a simple code line, just like today it is critical to operate a spreadsheet program or a text editor. So far, Polish employees have mastered neither of these skills and this might be a key barrier to development in the next decade.