Tydzień w gospodarce

Category: Trendy gospodarcze

Tens of thousands of customers are dependent on the decision whether the United Kingdom will remain the financial center of Europe. In contrast to trade in goods, there is no single system of trade in services for suppliers from outside the European Union (EU). The service market is not protected by tariffs, but it is limited by non-tariff barriers, such as licenses and regulations. The issue of trade in financial services is not regulated by EU’s agreements with non-member states. For example, the trade agreement between Canada and the EU, which liberalizes the trade in services, does not facilitate the provision of financial services for companies without a local license.

In an interview with the Bloomberg agency in Davos, the British Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond emphasized that financial services must be part of the final trade agreement. The inclusion of financial services in the Brexit agreement between the UK and the EU has become one of the most controversial areas of the negotiations. The chief EU negotiator Michel Barnier warned that Brexit also means that British banks will lose the so-called „passporting rights” that allow them to freely sell their services in the single market.

For the British government the issue of the free movement of workers from the EU is a „red line”, where no concessions can be made. If the government sticks to its red lines, then the British banks will lose their unconstrained access to the European market. The transition period is due to start in March 2019. British entrepreneurs and bankers have repeatedly urged their government to clarify what rules will apply after that point. Such information is necessary for companies to be able to invest and hire foreign employees. At the end of January, three ministers – the Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond, the Secretary of State for Brexit David Davis and the Secretary of State for Business Greg Clark – published a letter reassuring entrepreneurs that the United Kingdom would follow EU rules during the transition period. All the sectors – from agriculture to financial services – will be able to trade with the European Union on the current terms. Problems will arise when Brexit actually takes place, however.

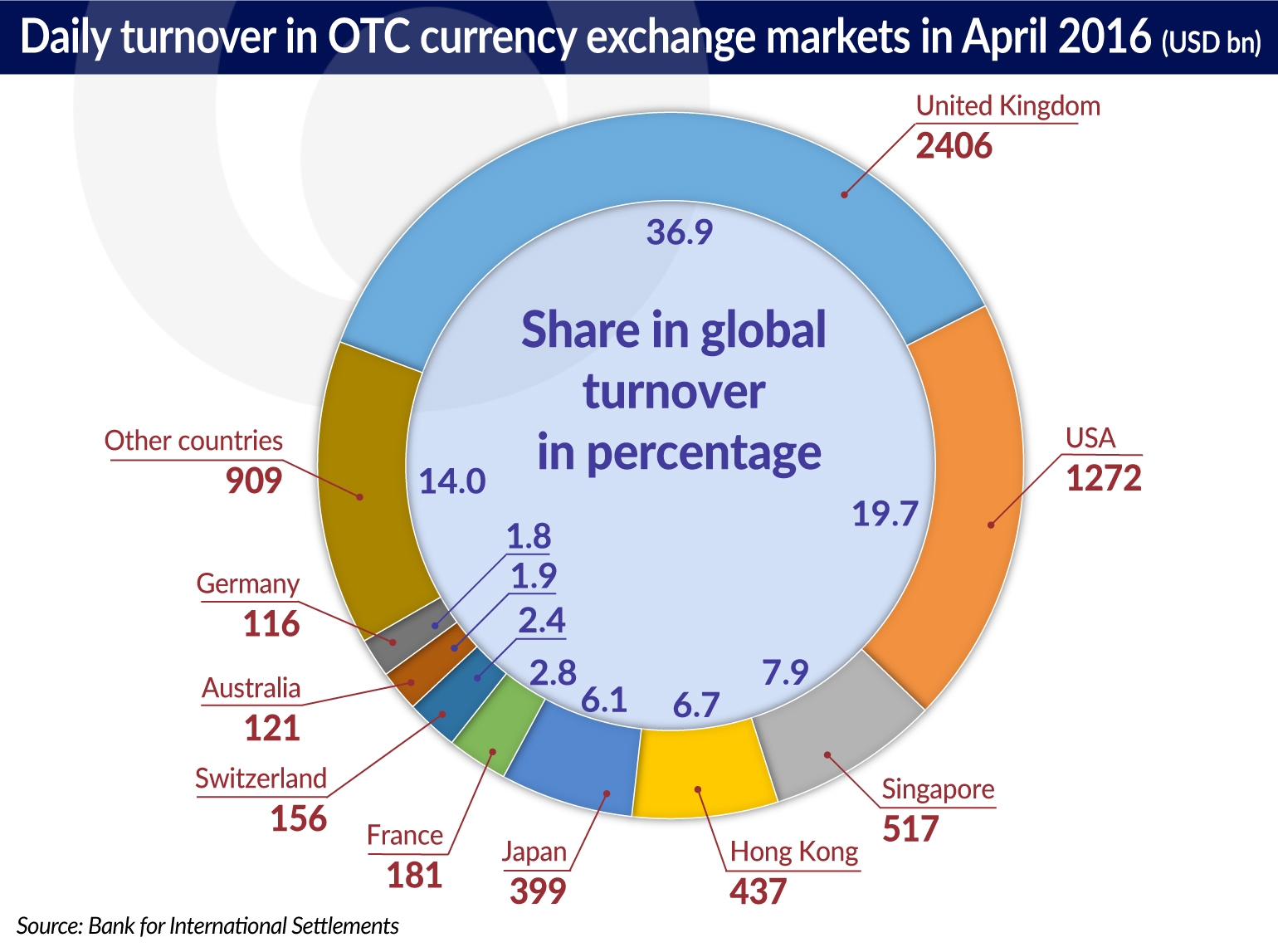

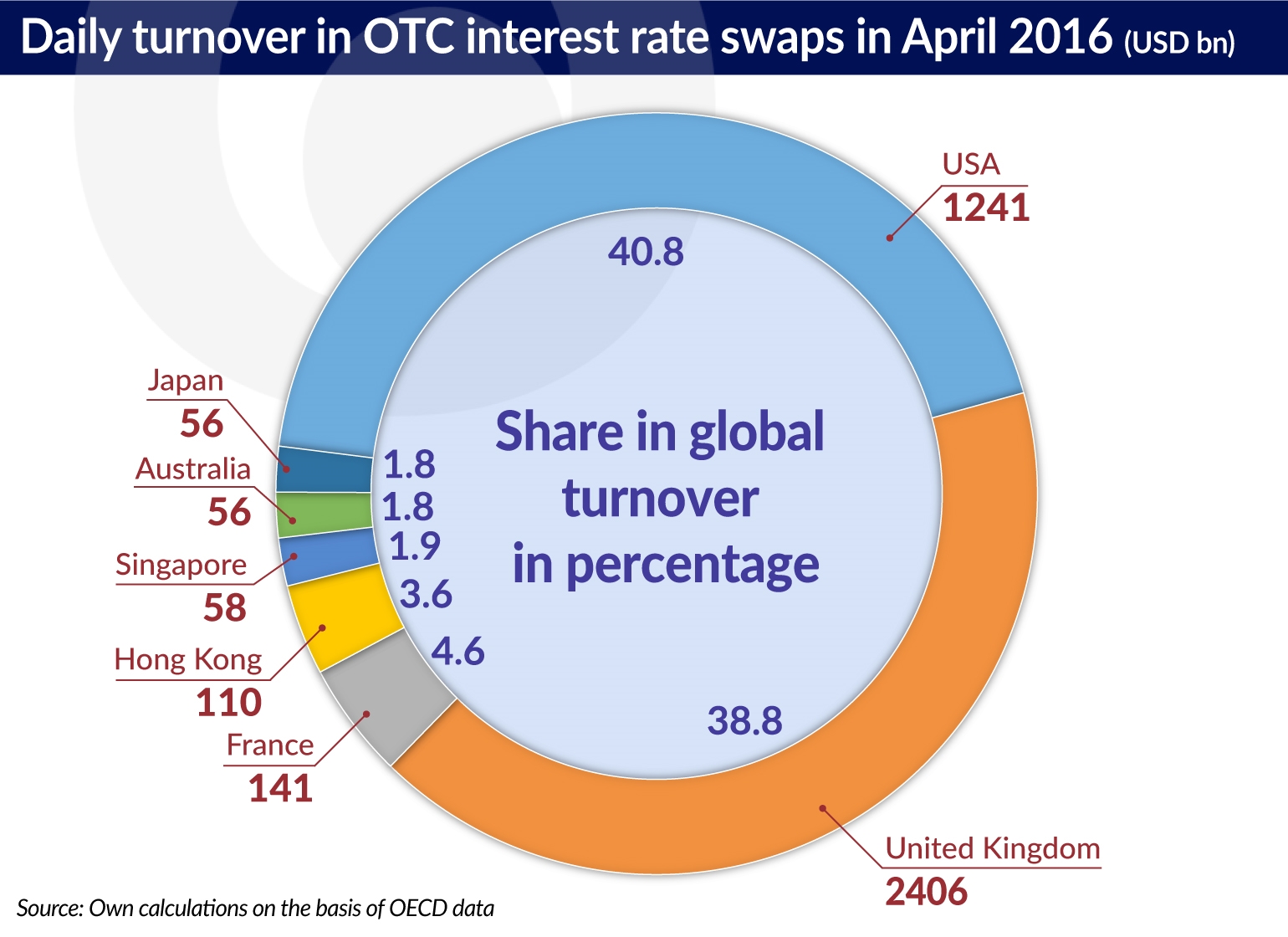

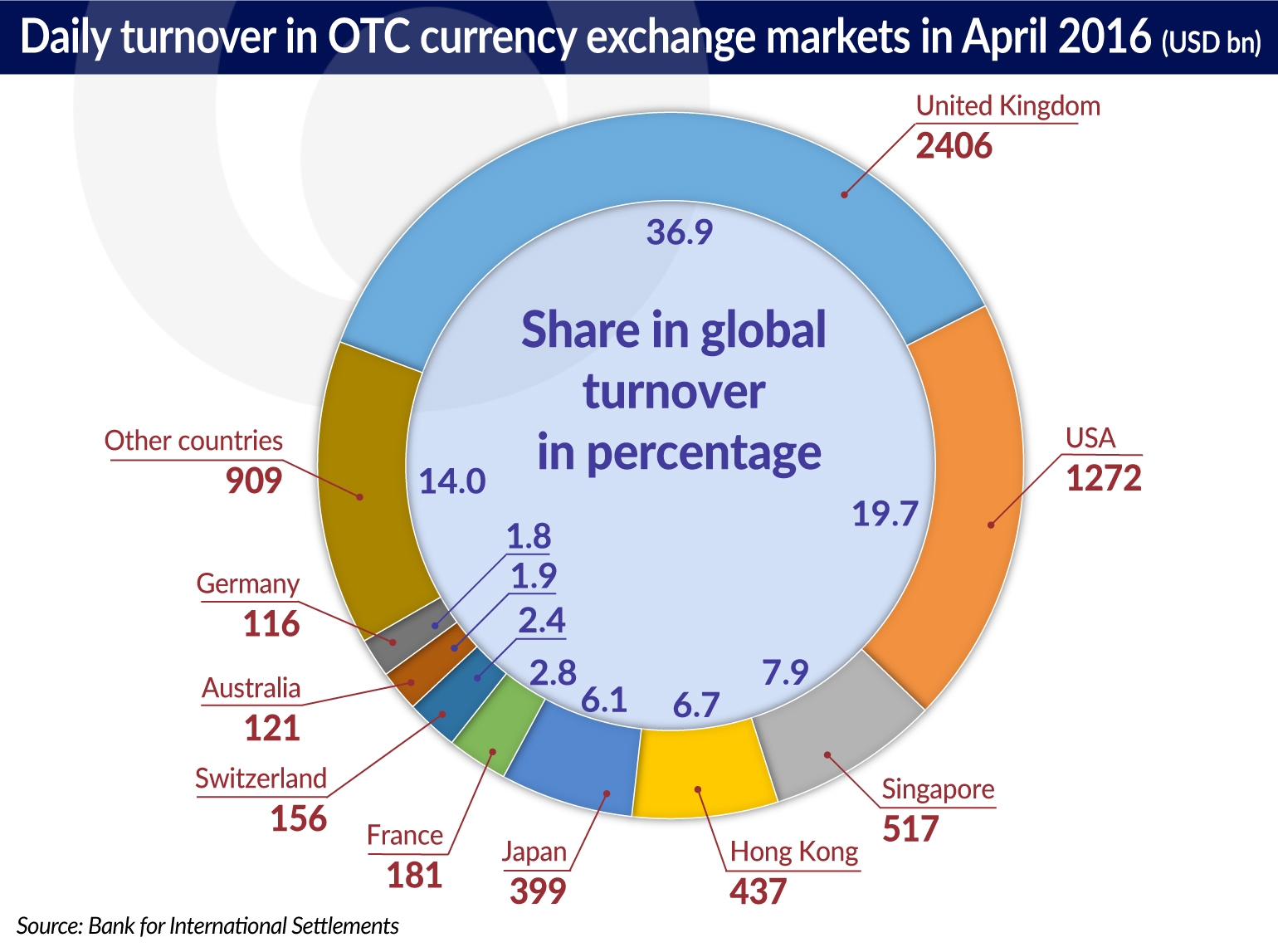

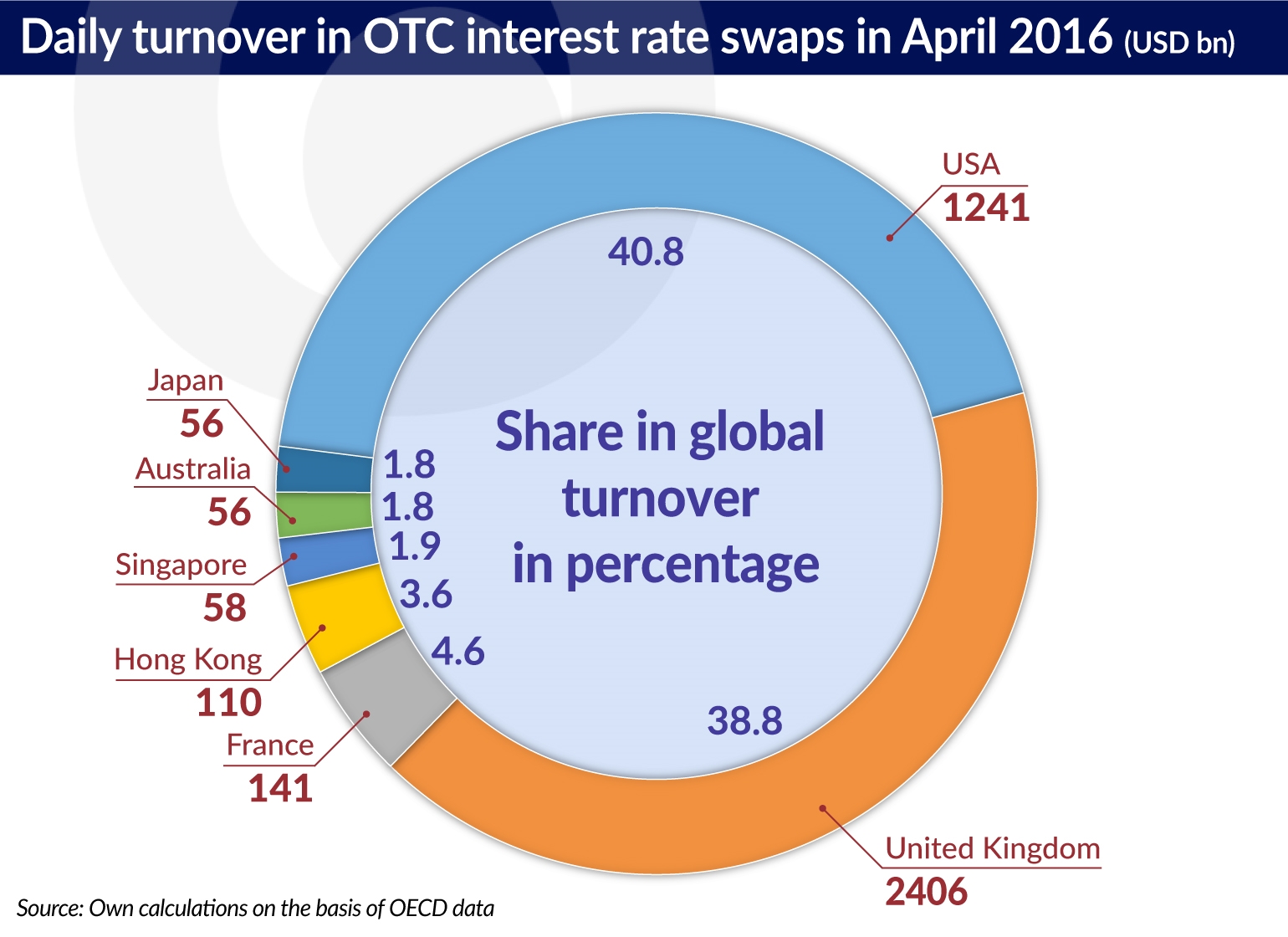

London is the largest provider of complex services in the European Union and the largest financial center. The United Kingdom is the second largest exporter of services (not only financial ones) in the world. Tens of thousands of customers and banking services worth billions of EUR depend on whether the United Kingdom will remain the financial center of Europe.

Thousands of companies on the continent use the services of British financial companies, without necessarily realizing it. British banks are often responsible for various transactions, from public investments financed by governments with loans, to loans to small and medium-sized enterprises. European companies exporting goods outside the euro zone hedge against the foreign exchange rate fluctuations by purchasing currency options on the London market. European corporations planning mergers or acquisitions use the services of specialized London-based investment banks.

Financial services and related business services, such as insurance, accounting, legal advice and management generate nearly 11 per cent of the United Kingdom’s GDP, employ 7.3 per cent of the people working in that country, and provide a significant surplus in its foreign trade.

TheCityUK, a lobbying institution representing British financial and related services, and the Office for National Statistics, presented data for 2016.In 2016 exports of such services increased by 15.8 per cent, up to GBP95.7bn (EUR108bn). London is the most important financial center, but over half of the exported British financial services is generated outside of that city.

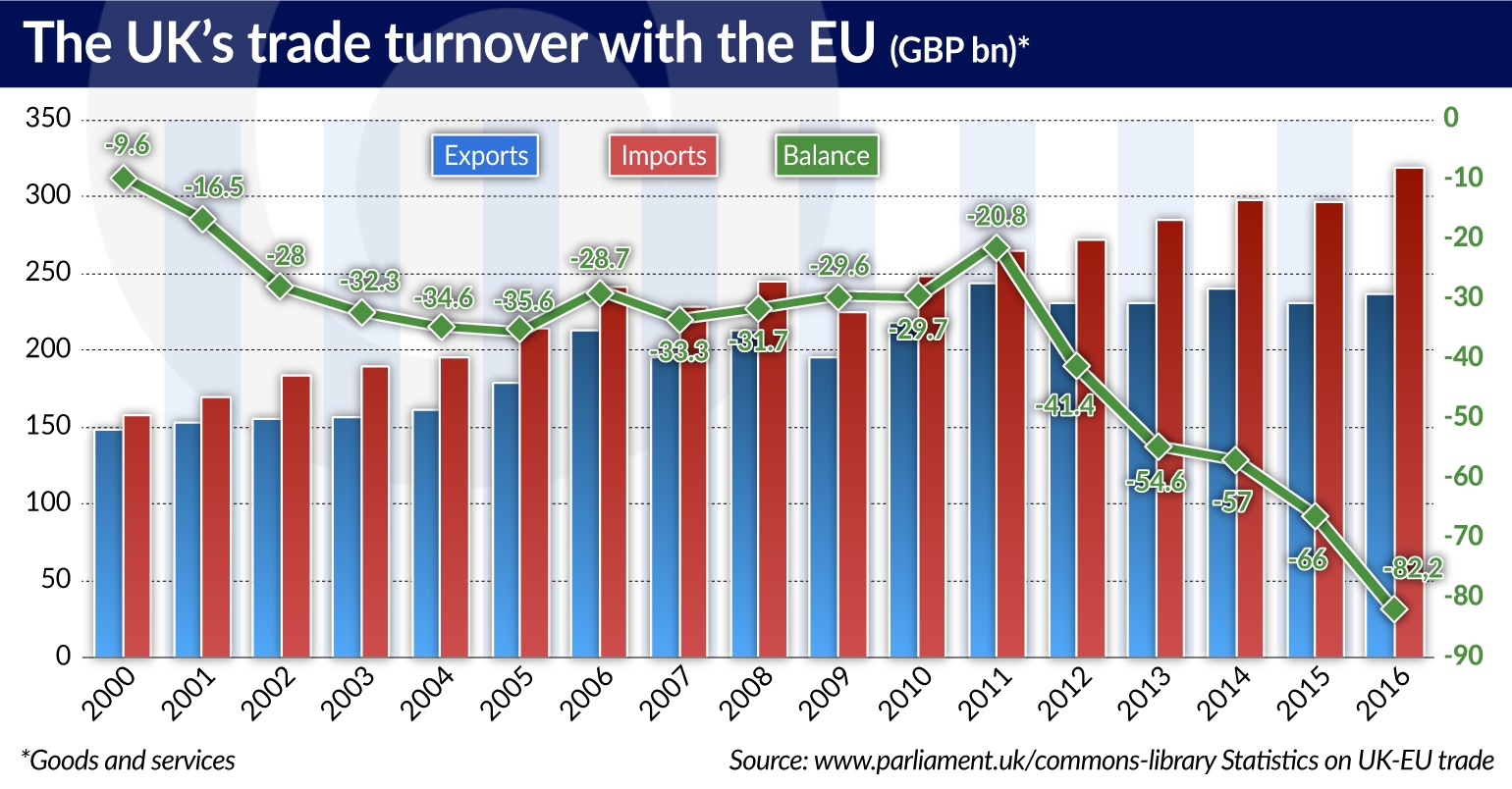

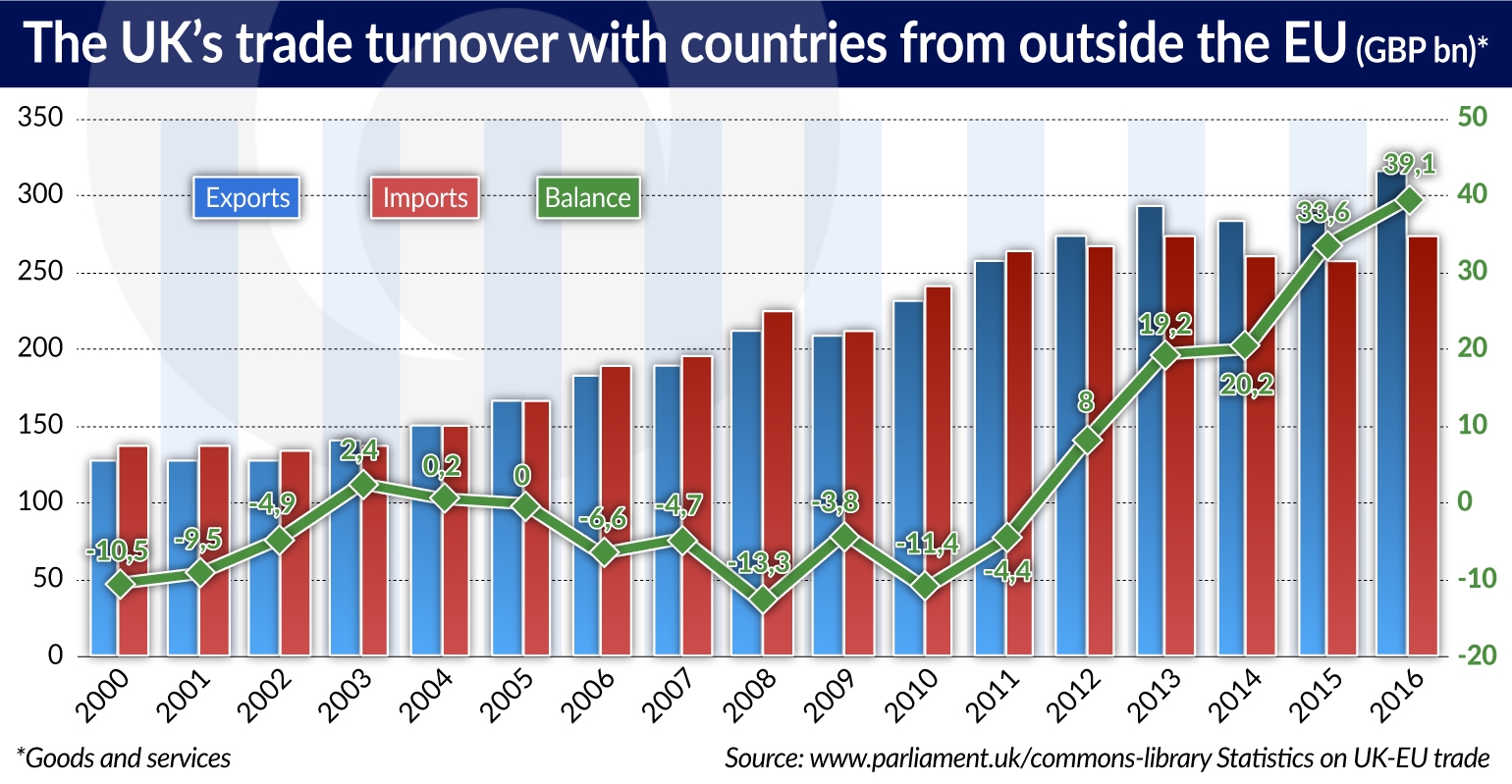

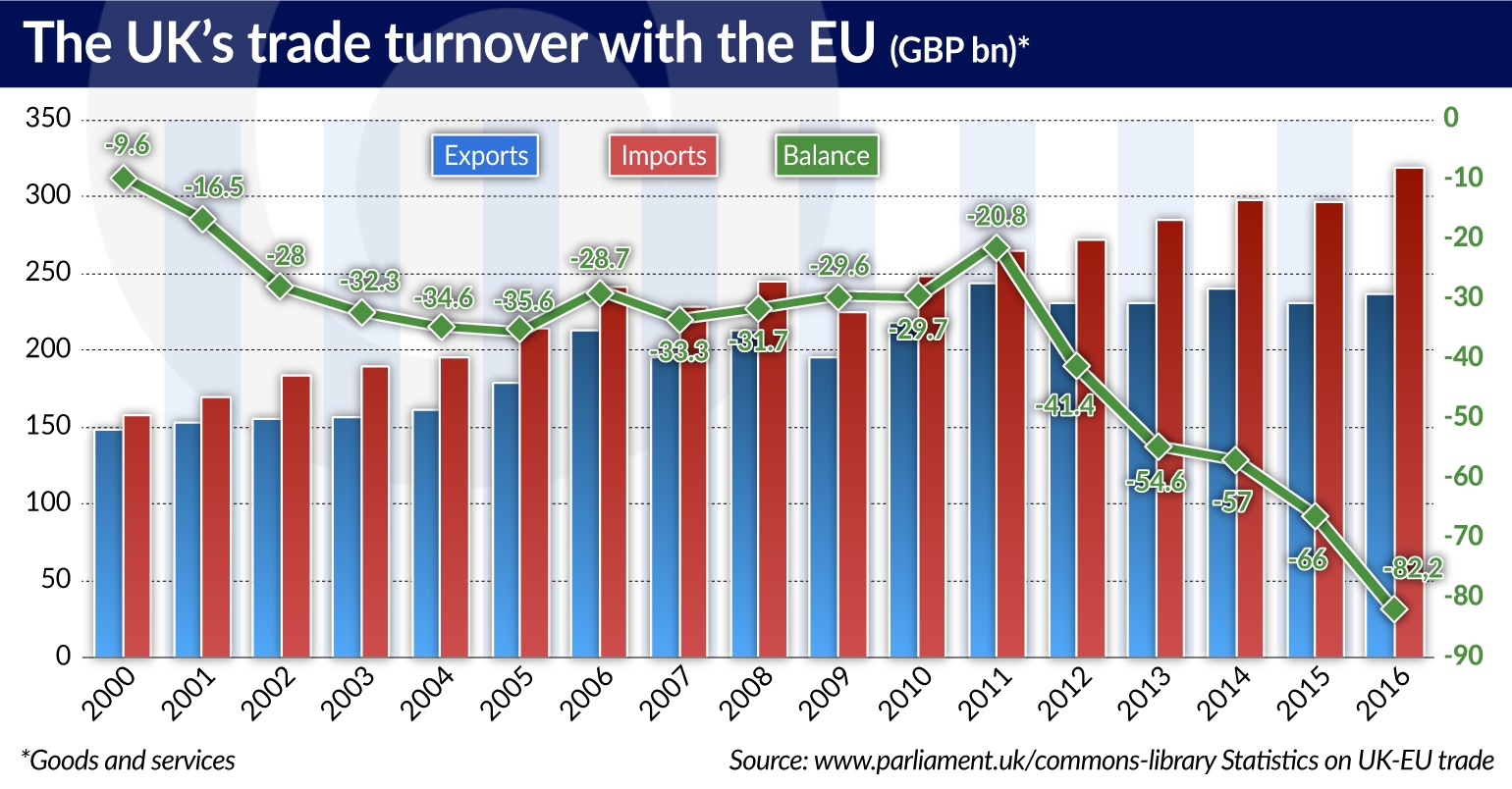

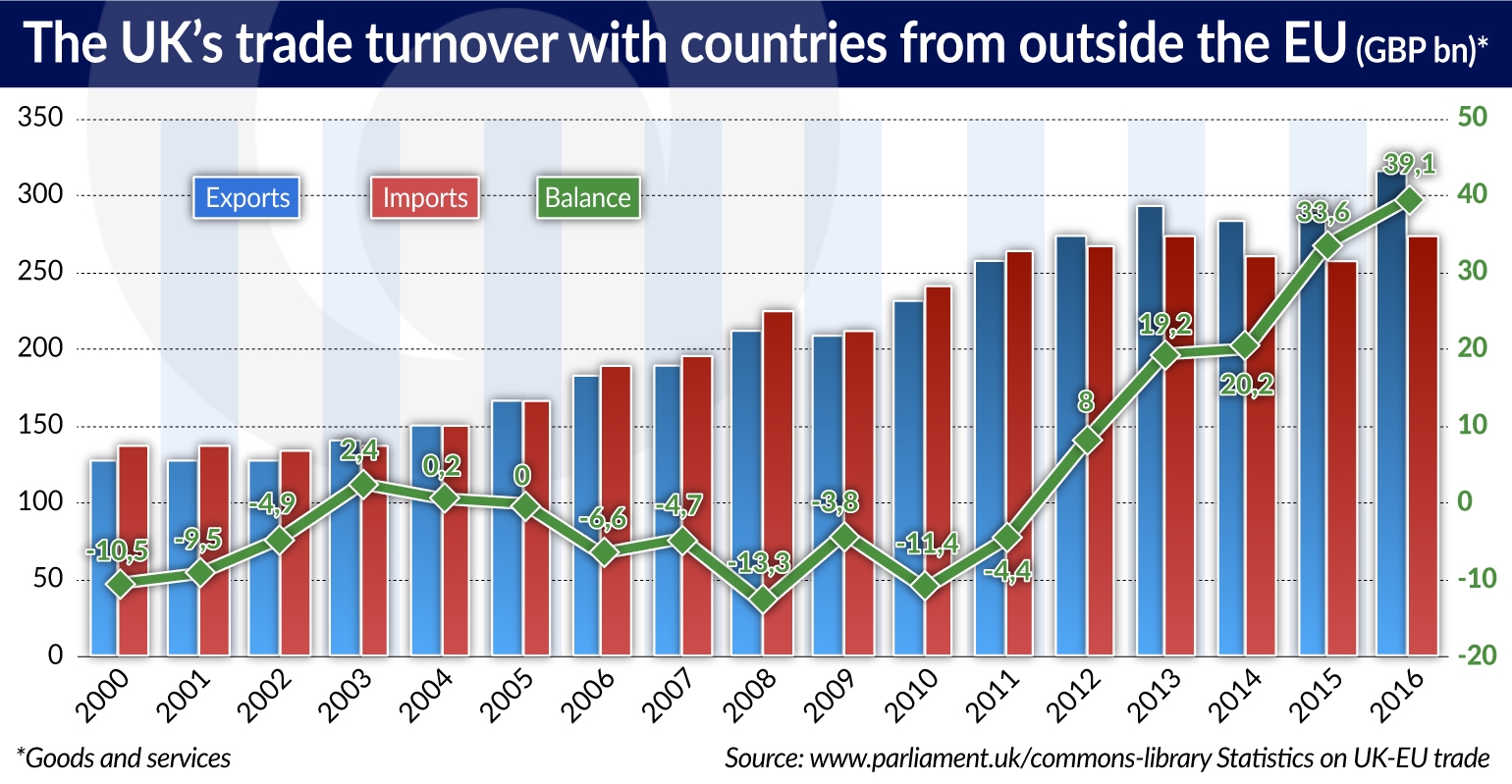

In 2016, the United Kingdom imported GBP4bn worth of financial services from the European Union, and exported services worth GBP27bn. The exports of other business services amounted to GBP24bn, and their imports reached GBP18bn. The surplus in the trade in financial and business services has reduced the United Kingdom’s negative foreign trade balance by GBP29bn.

Some 37 per cent of British services (including non-financial services) are sold on the market of the European Union. The EU is the recipient of 44 per cent of British financial services. The second largest recipient of British services is the United States, which account for 16 per cent of those exports. Switzerland, Japan and Australia account for 2 to 5 per cent of the British services market.

The services supplied by British insurance companies account for a significant portion of these exports. In 2016 the export of such services was worth almost GBP18bn. The export of insurance services includes the insurance of the shipping of imported or exported goods, direct insurance (e.g. aviation or maritime accident insurance), reinsurance, pension funds. The European Union is the largest recipient of services of this type.

The report entitled „Brexit: financial services” from December 2016, which was commissioned by the British House of the Lords, states that „the interconnectedness of the UK financial system presents serious difficulties for firms and the government in determining the impact of changes to the relationship between the EU and the UK”.

The report cites the words of Alex Wilmot-Sitwell, the head of Bank of America Merrill Lynch’s European operations: „It is not a Lego set in which little pieces can be built up and put somewhere else. The interconnectedness is very significant and we need to be assured what happens when the UK leaves the European Union”. Other commentators compare the situation to the popular game Jenga, in which an unskillful removal of one block causes the entire tower to tumble.

According to the report by the House of Lords, the British financial system will be very difficult to relocate to the continent, due to the existing cultural differences, as well as the interconnectedness of banks. A large part of the British financial industry that will lose the European market will not be recreated in Dublin, Frankfurt or Paris, but will rather relocate to New York. This will also be disadvantageous for companies from the European Union, for instance, due to the greater distance. A simple example is that London is the main center for euro-denominated interbank clearing and settlement operations. After the Brexit referendum in June 2016, the European Central Bank tried to create such a system of settlements outside of London, and this matter was the subject of many discussions of politicians from the eurozone countries. The task turned out to be more difficult than expected, however.

The services of the British financial sector affect the condition of the entire economy both in the United Kingdom and elsewhere. According to the analysis of the global consulting company Oliver Wyman, they generate annual revenues outside the financial sector amounting to approx. GDP200bn, GDP90-95bn of which are domestic revenues, GDP40-50bn are revenues in the EU, and GDP55-65bn are revenues relating to the rest of the world.

The single European passport allows British banks, insurers and other companies providing financial services to conduct business activity in other countries within the EU and the European Economic Area (EEA). Such „passports” are held by about 5,400 financial companies registered in the United Kingdom. On the other hand, around 8,000 EU companies use it to conduct their business activity in the UK. Companies holding a „passport” can provide services in other EU Member States without obtaining additional permits. These services can be provided either directly or through subsidiaries operating abroad. This requires the permission of a regulatory authority only in the company’s country of origin and does not involve additional costs. The „passporting” rights are defined in several legal acts of the European Union. A single company may hold a „passport” for several different types of services.

The European legislation allows for the access of a „third country” (the United Kingdom will become the third such country after the conclusion of the Brexit procedure) to some areas of the financial services market. But according to the British Bankers Association (BBA), the procedure for obtaining access to the EU financial services market will be burdensome, costly and time-consuming. Moreover, the European legislation does not provide for the access of third countries to certain types of services. This applies, for example, to payment systems for retail customers. Access to such systems for banks from third countries depends on the legislation in the individual EU member states and will require obtaining additional permits.

The ability of service companies, including financial firms, to operate within one large economic zone, covering many countries, is something truly unique on a global scale. The World Trade Organization has led to a reduction in tariffs and non-tariff restrictions on cross-border trade. The existing free trade agreements – the European Union has concluded such agreements with South Korea, Singapore and Canada – have improved the conditions of the companies’ business operations in the countries covered by the agreements. But neither the WTO rules nor the free trade agreements regulate the issue of cross-border financial services. Free trade agreements are usually signed between countries which have diverging regulations concerning financial services and supervision, and because of that it is so difficult to allow for cross-border services in this field.

A foreign financial company – a bank, a fund or an insurance institution – can usually register business activity abroad without much trouble and submit to the local regulatory provisions. But the unconstrained provision of cross-border financial services requires a new model of international agreements.

The negotiations between the EU and the UK are difficult mainly for political rather than economic reasons. The „red lines” drawn by both sides are meant to emphasize their determination. Some European politicians want to show their voters that a country leaving the European Union has been properly punished, while the politicians on the other side of the English Channel want to fulfil the demands of those Britons who voted to leave the EU in the referendum due to fear of immigrants from Central Europe.

That is why they insist on the right to limit the entry of EU citizens into the United Kingdom, even though they know that the British economy needs immigrants. Both sides are also treating their „red lines” as bargaining chips in the negotiations. The German politicians are suggesting that they are willing to accept a deal that would preserve the current rules for the provision of cross-border financial services, on the condition that the United Kingdom commits to an adequate contribution to the EU budget.

Both sides could lose out if they fail to strike a compromise. British financial companies will reduce their turnover and employment, and some of them will move to the other side of the Atlantic. Meanwhile, the Europeans will lose access to certain modern financial services. Further adverse consequences, such as a long-term slowdown in economic growth on both sides of the English Channel, are likely, although it is difficult to accurately predict them.

Due to the high degree of harmonization of financial regulations, a deal going beyond the standard scope of free trade agreements is technically easy to achieve. Such an arrangement would have to include:

Of course, British banks will not be covered by the principles of the Banking Union, if it is finally establish. It is possible, however, that both sides will provide each other with mutual support in crisis cases — e.g. that some part of British deposits with be covered by the guarantees of the European Guarantee Fund. Or the other way round — that British banks will be providing liquidity to European banks.

It’s another thing is whether such an agreement regarding the financial sector could last for a longer period of time. It is clear that regardless of the declared cooperation, both sides would have their own separate legal systems and would focus on their own priorities in the development of new regulations. As a result, after some time both regulatory systems will gradually diverge. This period would be used by the economies of the UK and the EU to ensure smooth adaptation to the new conditions. If the cross-border financial ties are abruptly severed, this could bring consequences that are currently difficult to predict.