Tydzień w gospodarce

Category: Trendy gospodarcze

(D. Gaszczyk/CC by Jean Pichot)

Public employment services in Poland consist of over 300 poviat and 16 voivodeship labour offices. The main task of labour market institutions both in Poland and worldwide is to match unemployed people to suitable job opportunities.

Helping people at risk of long-term unemployment and occupational inactivity to develop the skills and competence to become employable is another key task of such services. These include, i.a., training, career and employment counseling and subsidising jobs. Maintaining public employment services is legitimate only if their activities contribute an additional value to that provided by seeking a job on one’s own or by private job agencies.

An average poviat labour office is a strongly bureaucratic institution. Only one-fourth out of 20 thousand office staff is directly involved in job placement. Crippled communication between labour offices and employers, burdened with the red tape, has been evidenced by the experiment by Joanna Tyrowicz (Why does job placement not work in Poland? The results of experimental research. PKPP Lewiatan, Warsaw 2013). The researchers sent fake job offers to all labour offices via e-mail. Some 60 percent of poviat labour offices did not respond to a prospective employer at all. In the remaining cases, career officers requested additional forms to fill in before an offer is made available to the unemployed.

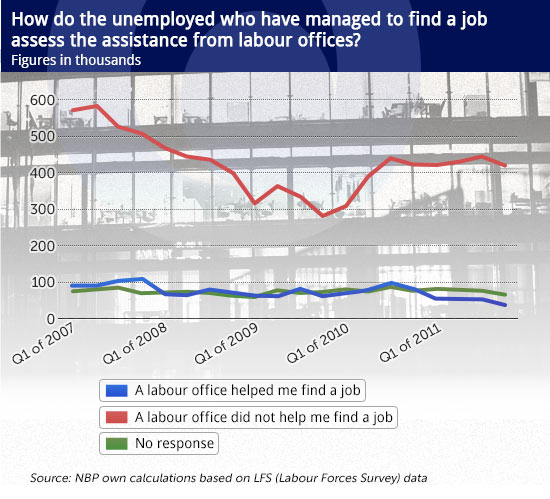

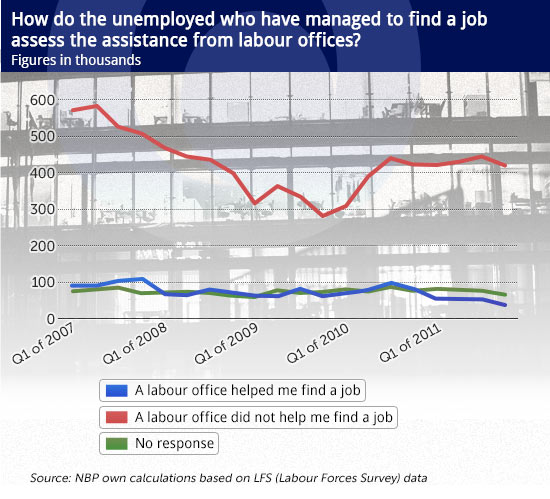

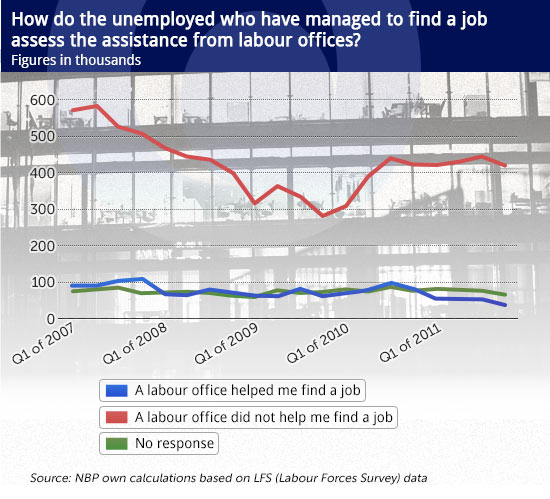

Moreover, the unemployed themselves have admitted that the assistance of labour offices in finding a job is very limited.

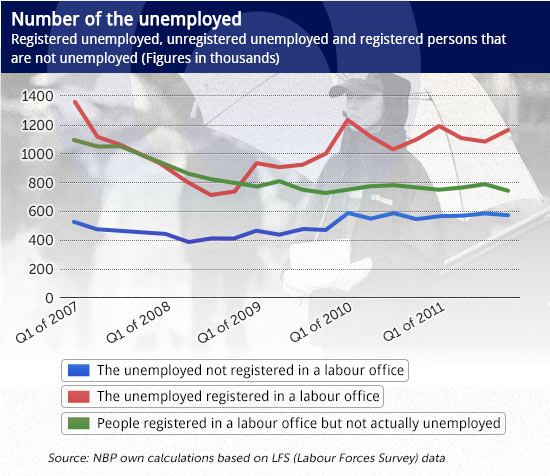

The army of the unemployed who register as unemployed only to benefit from free health care services constitutes the biggest problem for labour offices. According to the data obtained from the Labour Force Survey 40 percent of the people registered in labour offices are not actually unemployed (see Figure 2). These persons either work in the grey zone or are not interested in undertaking any job, e.g. women caring permanently for a family member. We may refer to them as fake unemployed.

An average career officer has no way of knowing who is actually looking for a job and who has registered for other reasons. Eventually, the fake unemployed are offered vocational activation although they do not really need it. Considering limited resources allocated for vocational activation policies, it means that some of those who really need them are deprived of assistance and public funds are being wasted.

Under the effective legislation a career officer may remove an unemployed from the register if he/she refuses to participate in vocational activation. Some labour offices have announced that they are going to apply this regulation more often in order to get rid of fake unemployed. Instead of improvement, such a policy may lead to the situation becoming even worse. The fake unemployed will most likely adapt to the new circumstances. If a labour office suggests that they should take part in a training, they will not be able to refuse. Consequently, their participation in vocational activation will contribute to displacing those actually unemployed even more.

Another approach is to turn a blind eye at the fake unemployed. Letting the fake unemployed to come forward without any negative consequences allows to concentrate on those in need. This solution has been applied for instance, by the labour office in Gdańsk. Although such practice seems rational from the economic point of view, it raises certain doubts whether it complies with the law.

The elimination of a reason for which the unemployed register in labour offices is the best way to solve the problem. All unemployed should be covered by universal health insurance. This solution, although it may seem far-reaching, would not entail a considerable budget expenditure.

Nowadays almost all Poles are covered by health insurance. The state pays health insurance contributions for the unemployed, including the fake unemployed, and for most of the economically inactive. People who work will continue to pay their health insurance contributions from their wages as they do it now. The only difference would result from covering people who, for some reason, do not hold health insurance. According to the estimates, approximately 2 percent of Poles are not insured. What is more, universal access to health care is guaranteed by Article 68 of the Constitution.

The advantages for labour offices could not be underestimated. Some 40 percent of the unemployed would disappear from the registers, while politicians could claim success in media. After reducing the red tape, more career officers could be assigned to working directly with unemployed and only those actually unemployed would find their way to labour offices.

Vocational activation of particular intensity targeted at unemployed with regard to their particular needs is another step forward in the state’s effort to improve the performance of employment services. Persons with qualifications highly appreciated in the labour market require the least of attention. The only thing that career officers have to do is notify them about job offers. People with low qualifications or qualifications in fading jobs constitute the second group. A labour office should help such people to acquire new skills that are sought after by employers.

The third group to be distinguished consists of the unemployed who are “far from the labour market”. This group includes the people who have been looking for a job ineffectively for a long time. After a number of disappointments, their self-esteem and attitude towards further job searching deteriorates (the so-called learned helplessness), and also employers are not willing to recruit a long-term job seeker. These persons should be additionally offered personal intensive vocational and psychological counselling.

In order to offer assistance tailored to particular needs, a mechanism identifying to which group a job seeker belongs must be put in place. At present, this role is played by a list of persons in a difficult situation in a labour market included in Article 49 of the Act of 20 April 2004 on the promotion of employment and labour market institutions.

The list includes: people under 25 and over 50, single parents, long-term unemployed, people without vocational qualifications or secondary education, women who wish to resume employment after having a child, former prisoners, and the disabled.

The scope is too extensive as already 90 percent of registered unemployed constitute a group of “special treatment”. Besides, the statutory list of social groups that may be in a worse situation totally overlooks the problem of determining what is the actual situation of a given person (it should be noted that 40 percent of the registered unemployed are fake unemployed).

On this basis, it is impossible to determine who needs more-than-average support. The Ministry has taken note of the problem by the – a postulate of introducing a system of profiling the unemployed based on their own declarations has been included in the assumptions for the amendment to the Act.

Commercialisation of job agency services could contribute to further improvement of labour office performance. Contracting labour market services, or commissioning vocational activation to private undertakings, has been introduced on a wide scale in other countries. In Poland, the extent of contracting is very limited and the experience acquired in this field does not inspire with hope. The outcome of a pilot programme concluded recently in Gdańsk has been worse than expected.

The privatisation of job agency services, that is a situation where all or nearly all labour market services are contracted and commissioned to private entities, is another step forward. This option was adopted in Australia in 1998 and in the Netherlands in 2001. The entities with the highest efficiency in assisting the unemployed are granted a financial bonus. The entities that have not achieved satisfactory results are not invited to tenders any more.

Strong economic incentives for increasing the effectiveness of services bring an undeniable advantage (an education voucher is a similar solution in the field of education). While designing new solutions, negative effects, such as cream-skimming, i.e. a situation where service providers actually offer help only to those who have the highest chance of returning to the labour market, should be taken into consideration.

The lack of knowledge of which vocational activation activities would be the best from the point of view of job seekers is another shortcoming of public employment services. The evaluation of market policies in Poland consists in examining what percentage of the unemployed taking part in vocational activation has effectively found employment. Still, such simple evaluation is hampered by the fact that some people who have been successful would have found a job even without participation in vocational activation. In such case, assistance provided by a labour office was pointless and financing it was a waste of money.

A fair evaluation of labour market policies is ensured by the randomised experiment method based on random assignment to the survey and reference group (not taking part in vocational activation). The evaluation of effectiveness consists in comparing the change in the probability of landing a job due to the participation in a vocational activation activity with the change in the probability in the reference group.

It should be emphasised that a properly performed evaluation needs to analyse relative changes in probabilities, not only their target values. Re-evaluation of labour market policies based on scientific methods may yield surprising results. Crépon, Duflo et al. (2013), used the randomised experiment method to analyse the advantages of intensive job counselling in France. Consultations with a specialist have increased a chance of finding a job. Still, persons not taking part in the programme have been at greater risk of remaining unemployed.

The net effect of counselling was negligible – chances of landing a job have shifted from one group to another, but have remained approximately at the same level in the entire population. All the same, such actions would have been considered effective according to Polish measures. Until now, randomised experiments for the evaluation of labour market policies’ effects have not been carried out in Poland and without the evaluation based on scientific methods we are walking through the mist. We do not know whether Polish policies create value added for the labour market or whether they only shift employment opportunities from one group of the unemployed to another.

Apart from significant organisational changes, functioning of labour offices could be enhanced by a number of minor improvements. The quality of labour office Internet services should be raised. True, public employment services run a website with job offers, but still its quality is far behind the leading web job offer portals. Moreover, a lot of the unemployed are not aware that such a portal exists. The possibility of preliminary registration via the Internet is a change that has been recently implemented.

Another idea is to create a newsletter with job offers. It has been announced in the United Kingdom that each unemployed using public employment services will regularly receive job offers selected for his/her qualifications and vocational experience via e-mail. The system will also notify an employment officer whether an unemployed person has applied for a job or not. If the number of offers ignored by an unemployed person is relatively high, an officer will invite him/her for a face to face talk to find out the reason for such developments and possibly to change the profile of offers sent to the person. The idea of a newsletter with job offers seems a promising tool in counteracting the discouragement of the unemployed without generating considerable costs.

Involvement of volunteers from among persons who have achieved professional success to work with the unemployed seems an interesting solution. The unemployed from disadvantaged environments consult their mentor about issues relating to job seeking, impression management, and career. The mentoring programme is practically cost-free – mentors do not charge for their work. Building social capital between persons from various environments is an additional advantage of mentoring.

In the above essay, I have outlined a number of areas related to the functioning of labour offices in which there is room for improvement. However, to be frank, I must admit that these changes will not be a remedy to growing unemployment stemming from slow economic growth. Enhancement of the job agency system will bring visible improvement only accompanied by economic recovery. The process of matching the unemployed with vacancies will improve in the long run. More efficient vocational activation policies will contribute to a decrease in the structural unemployment component. The reform of labour offices will create an opportunity for the rationalisation of public expenditure assigned for this purpose.

Jan Baran is an employee of the Institute for Structural Research.

The article Grappling with unemployment in the dark. It does not need to be that way has been selected the best paper in the second edition of the competition carried out by Obserwator Finansowy “If this depended on me, then…”. The winner has been selected by the Chapter of the contest headed by Katarzyna Zajdel-Kurowska, Member of the NBP Management Board, and other members: Dobiesław Tymoczko, Deputy Director of the NBP Finance System Department, journalists from Obserwator Finansowy: Jan Cipiur and Jacek Ramotowski, and Krzysztof Bień, Editor-in-Chief of Obserwator Finansowy’s website.

The title and internal titles have been added by the OF Editor.

OF