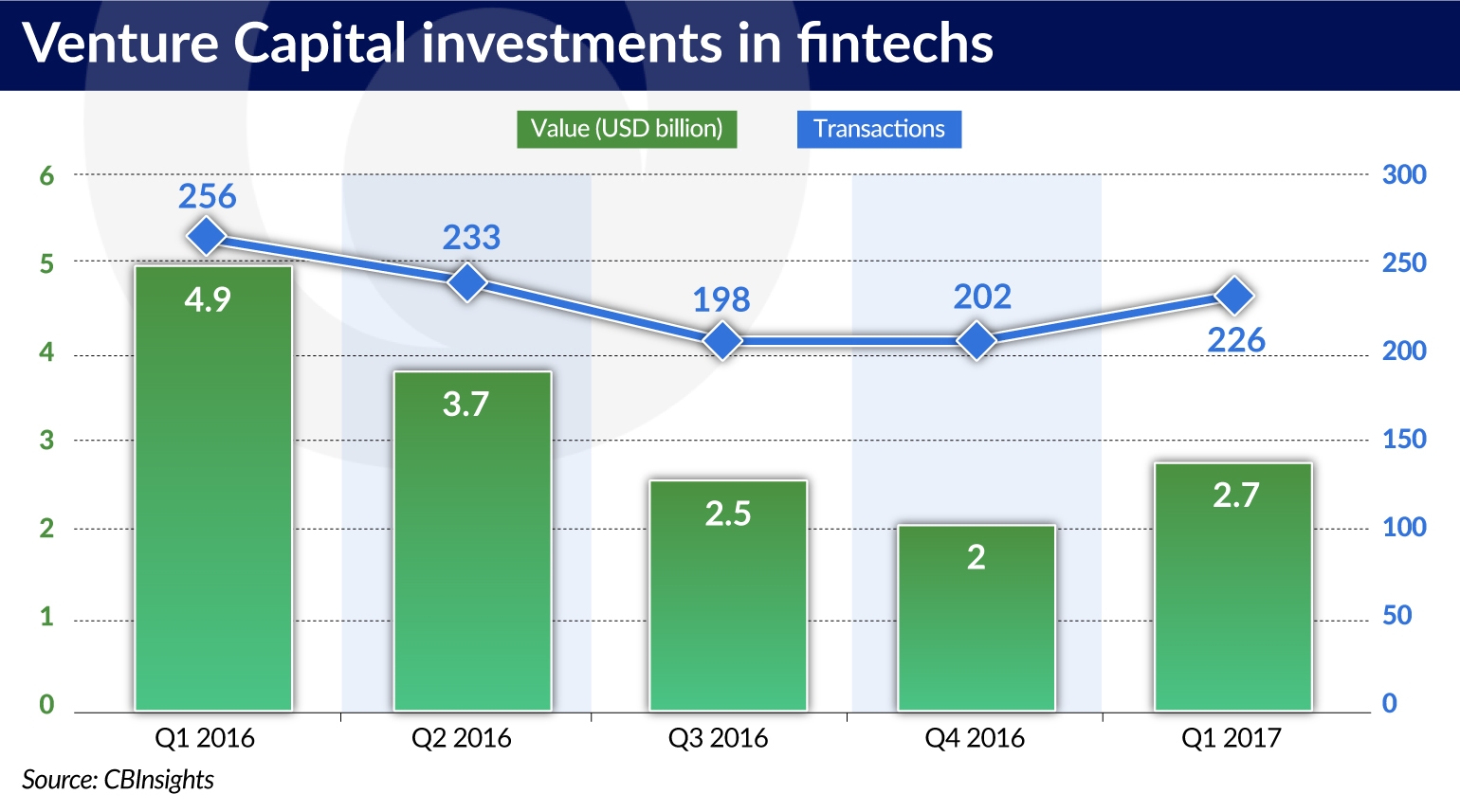

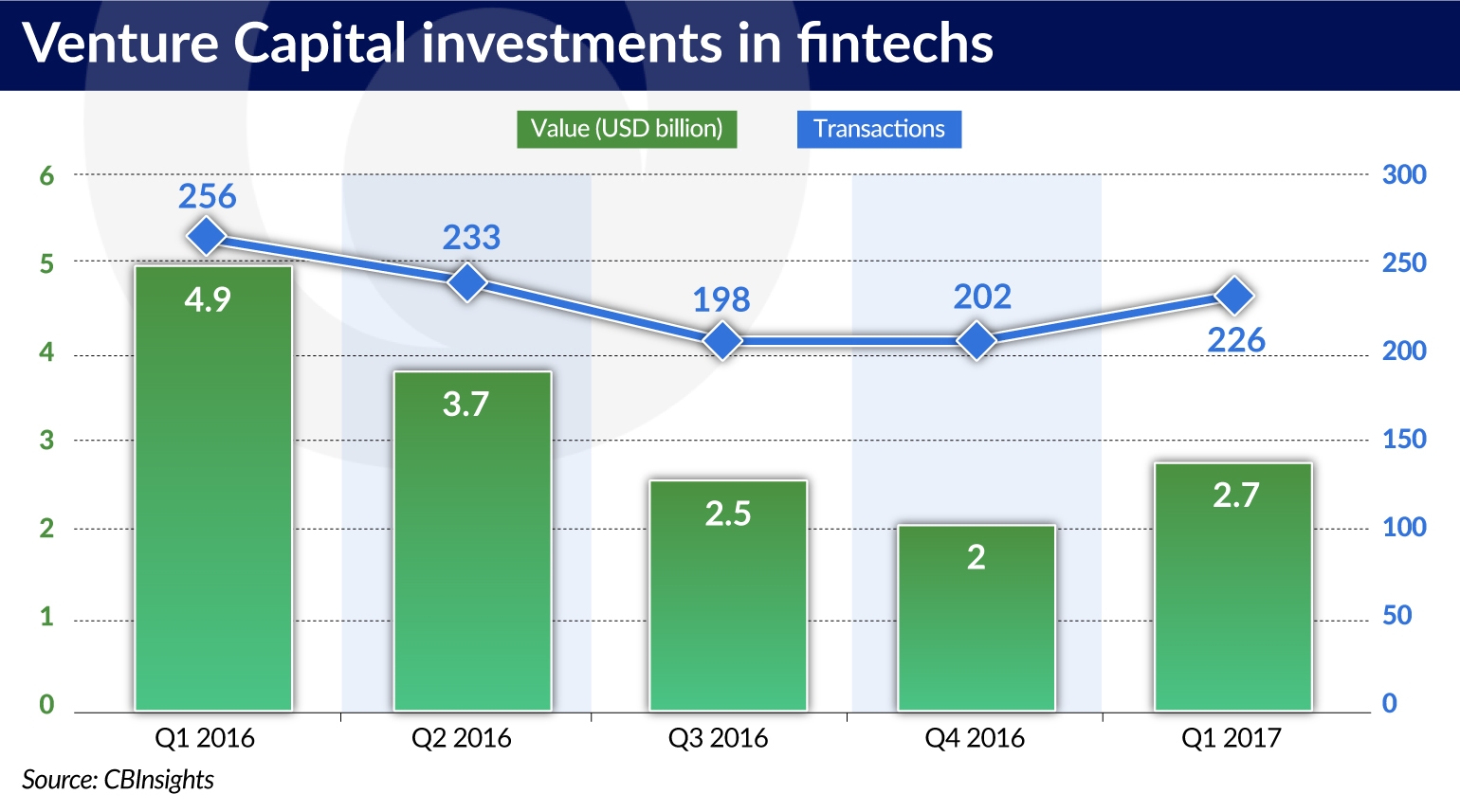

“Did someone cancel the fintech revolution?” ask the authors of the latest Accenture report. The revolution in the world of finance carries on, but it seems to have waned a little and changed its face. In recent months the number of searches for “fintech” on Google dropped by more than 20 per cent compared to last year. It’s mostly the investors who have lost their enthusiasm – in the past year investments of VC funds in technological companies was decreasing with almost each passing quarter, even though the number of transactions remains at a similar level. This means that they are simply worth less than before.

The valuations of start-ups are also normalizing. Studies conducted by McKinsey on 44 companies with a value exceeding USD1bn indicate that while the value of these companies increased by 77 per cent in the years 2014-2015, their growth slowed to only 9 per cent in 2016. The valuation of American fintechs looks particularly dramatic – in the first period the average growth was 54 per cent, and in 2016 there was a decline of 7 per cent.

Global banks did not carry out any huge investments either – in the years 2014-2016, VC funds belonging to HSBC, Santander and Barclays spent no more than USD500m combined. What’s more, it could be said that the global market is facing an inflation of technology companies — McKinsey estimates that there are over 12,000 such companies, that is 26 times more than the number of internet companies before the dot-com bubble burst in 2000.

The main reason for the disappointment of investors is that fintechs fail to meet the expectations in terms of scale of activity, and size of revenues and profits. According to a research carried out on a sample of nearly 700 fintechs, 79 per cent of them had revenues lower than GBP6.5m, and out of the 616 entities presenting their financial data, 49 per cent sustained a loss. One of the most well-known German mobile fintech-banks – Number26 – acquired a little over 300,000 customers, and the British Nutmeg, specializing in asset management, won just 30,000, even though it had set itself a goal of million customers.

What’s more, customers are acquired at the expense of low prices, and this approach is not a good basis for the development of sustainable business models. Many start-ups boast that they have reached the proof-of-concept stage, but in many cases that is their greatest achievement. In this context, a bright spot is the operator of money transfers, Transferwise, which announced a profit in May, after six years of activity.

The situation is better on the Chinese market. Alipay, which offers its clients a range of financial products, including insurance, has almost half a billion customers, and JD Capital (an investment and insurance group) has 250 million clients. The problem faced by these companies, however, is the limited scope of their international activity.

The difference between the activities of fintechs in mature markets and in emerging markets is that in the former they address their solutions to already banked customers (one exception are the Millennials), and in the latter – to the financially excluded, who cover from 20 to 80 per cent of the adult population. Hence the conquest of the market is easier.

The low level of internationalization and the lack of explicit specialization are also development limitations faced by Polish fintech companies.

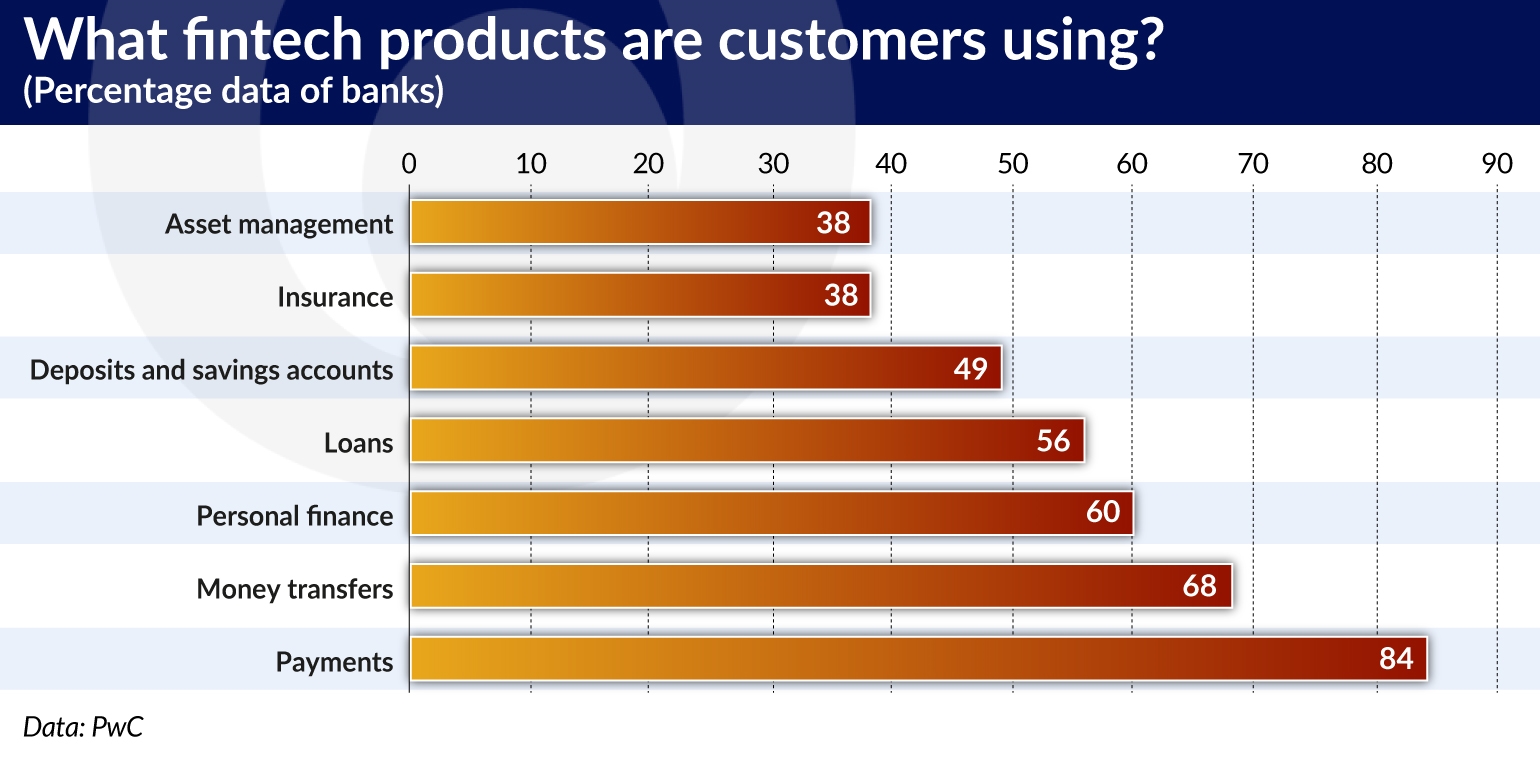

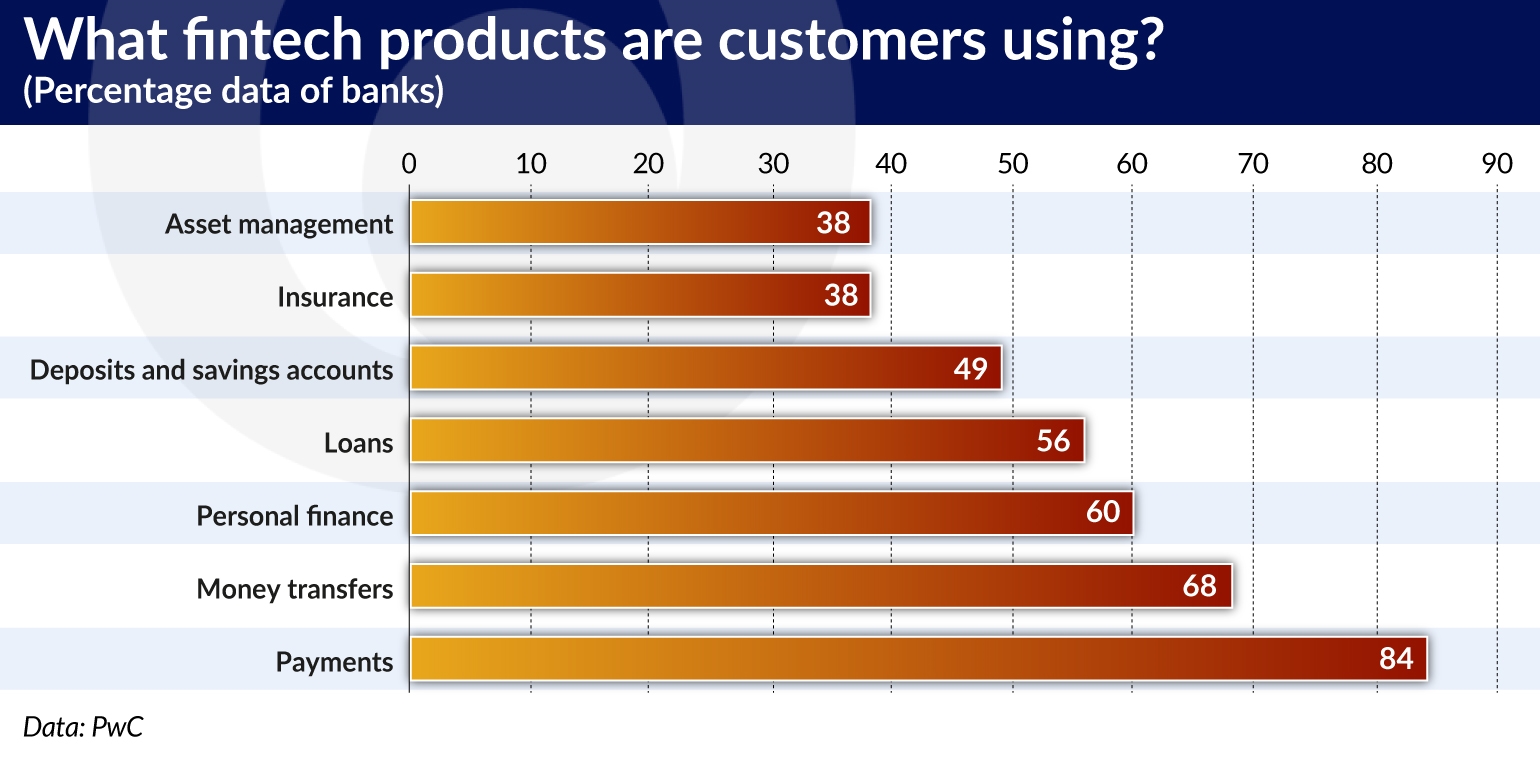

It’s hard to deny that fintechs have been successful in several areas – especially in the field of quick payments and money transfers. The banks admit that themselves. At best, these entities have taken over the implementation of about 25 per cent of retail payments and 10 per cent of revenues in the loans market. But acquiring new customers, quickly increasing revenues and lowering the cost to revenue ratio will be increasingly difficult.

Offering non-financial products can hardly be regarded as the target solution – the American company SoFi, operating in the field of finance for students and young professionals, extended the scope of its activities to networking services, and even career coaching.

The Finnish company Holvi – whose primary investor is the Spanish BBVA – which specializes in loans for SMEs, is also developing services as an online purchasing platform, a provider of accounting services, managing claims and cashflow.

A new feature is the cooperation of fintechs with corporations, through which they can offer their employees loans replacing payday loans and manage their finances, including fixed payments.

McKinsey identified as many as 30 areas of activity of technology companies – this moves fintechs away from the final customers and pushes them up the financial value chain towards B2B solutions. One example could be regtechs, providing solutions in the scope of banking regulatory costs, which received approx. USD1bn per year over the past three years from VC funds.

Looking at the current state of the fintech sector, it is impossible to overlook the first signs of its internal consolidation. The largest acquisitions take place in the remittances industry: in 2015 PayPal took over Xoom – the 8th company in the market, and now the Chinese company Ant Financial is fighting to acquire the 3rd largest player in the industry, Money Gram, for USD1.2bn. There are also many examples of acquisitions worth several tens of millions of dollars.

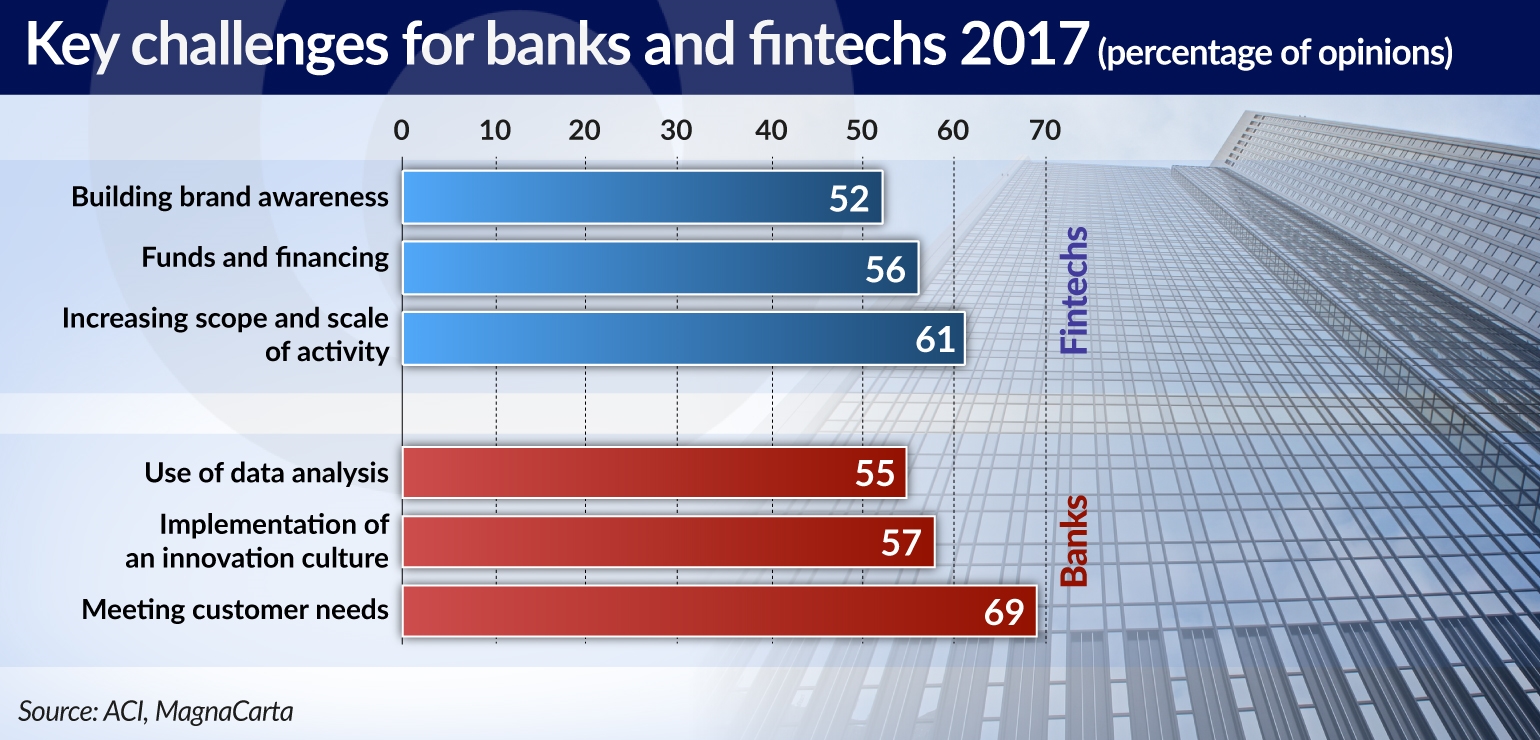

The surveyed representatives of fintechs and banks in Europe are surprisingly unanimous with regard to the challenges faced by the technology companies – it’s about building strong brands, ensuring a sustainable inflow of funds (from investors or in the form of revenue), and increasing the scale and scope of the activity.

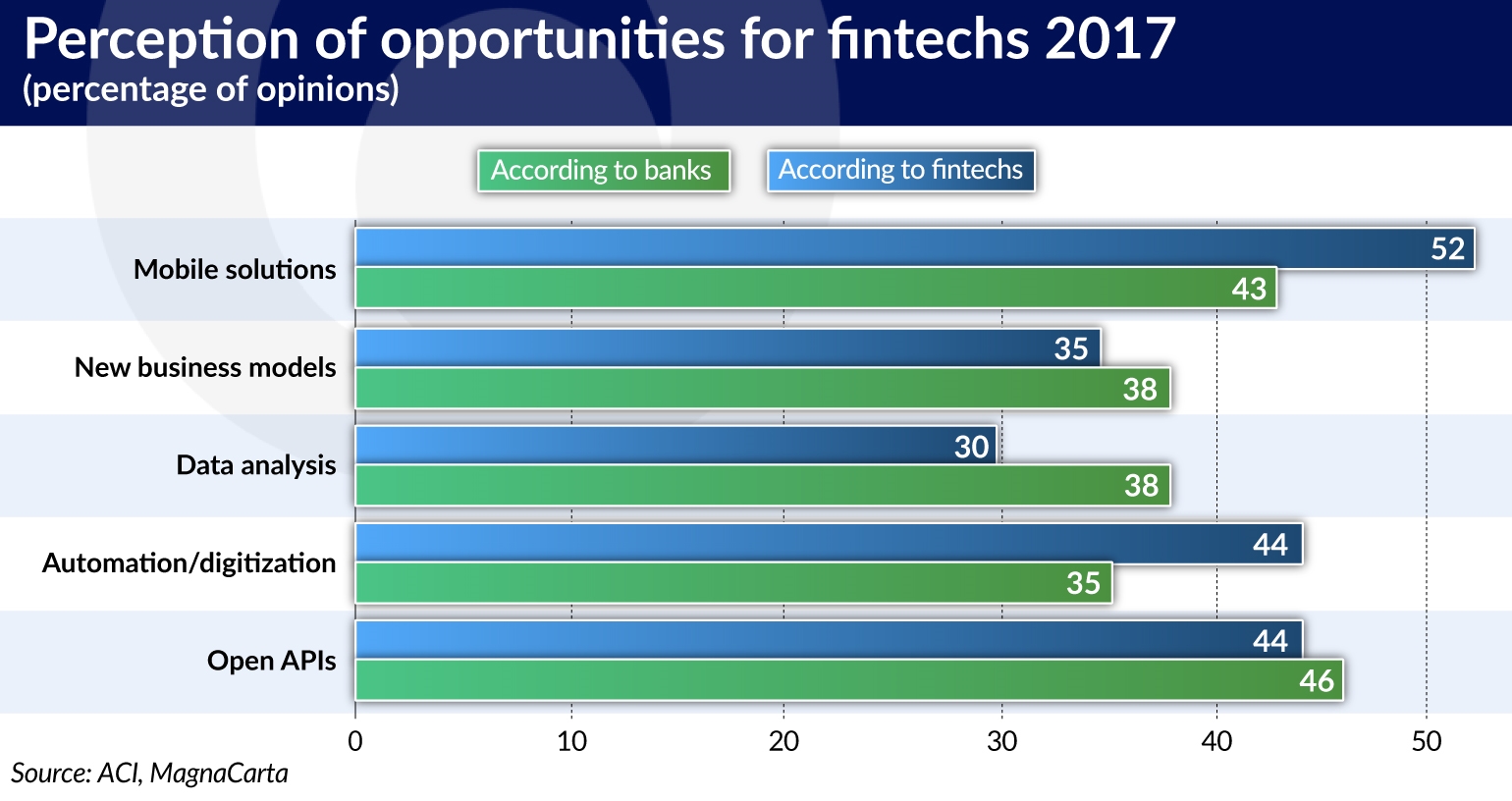

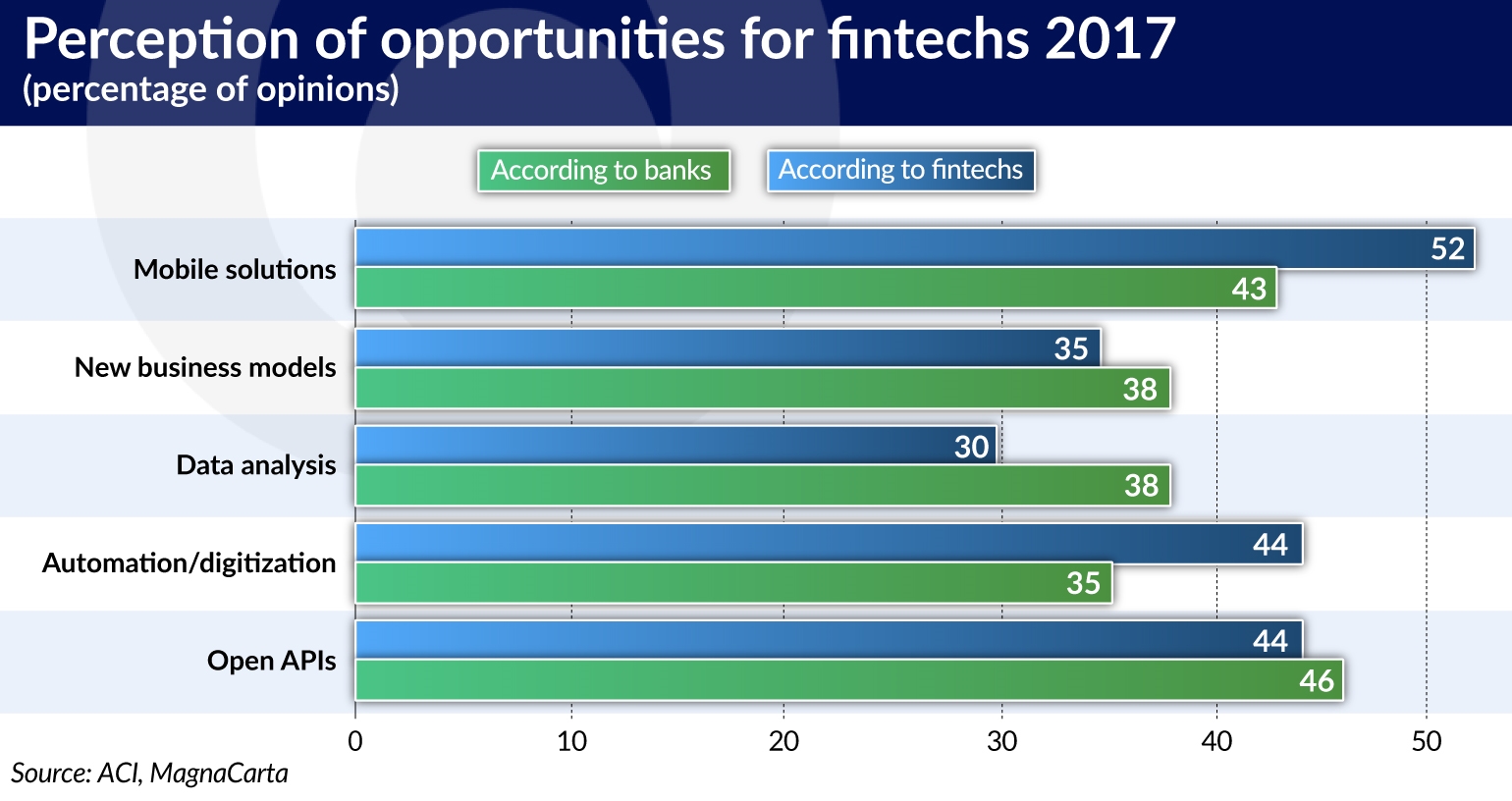

Meanwhile, the opportunities for fintechs are supposed to be based on the wide implementation of mobile solutions, data analysis, digitization and operation in an environment of open APIs, which is supposed to pave the way for new business models.

It is not difficult to notice that the start-ups could realize a large part of these opportunities in cooperation with banks, which face complementary challenges. According to the latest report of PWC, as many as 88 per cent of banks are concerned that they could lose revenue to technology companies, but 82 per cent expect increased cooperation with these entities in the next three to five years.

However, there are large geographical differences in terms of this approach – banks are the most interested in cooperation in Germany, where 70 per cent of banks have already entered into some kind of partnership with fintechs. This also applies to 53 per cent of American banks, 43 per cent of British banks and only 14 per cent of banks in South Korea. Only 17 per cent of banks in Poland, and 31 per cent in the world buy finished products or services from fintechs. Cooperation is based on various models – banks adapt the solutions of fintechs to their offers, and establish alliances in order to provide specific solutions to the customers. Banks may also provide financial support for selected projects of fintechs.

New products can also be co-branded, i.e. offered under two brands. This allows the projects of fintechs to be scaled much more quickly, and to reach customers outside their traditional segments. Only two years ago, the Australian bank Westpac introduced to its internet banking an application for the management of personal finance, provided by the American company Movena. In turn, the Spanish BBVA uses Destacame’s scoring models, based on payments for public services and media, to assess the creditworthiness of unbanked customers.

PKO BP is one example of a Polish bank which cooperates with fintechs in several areas. It runs the “Let’s fintech with PKO BP” accelerator program, which verifies the business model of young companies (their presentation could be seen in Gdańsk, at the Infoshare festival in May), it participates in the MassChallenge program, which is supposed to attract mature start-ups from Central and Eastern Europe, and it has announced the establishment of a venture fund to invest in more risky projects. Finally, it is the only financial institution in Poland to have taken over a fintech company (ZenCard) for the implementation of its business strategy.

Thus the future of fintechs is starting to increasingly depend on banks – according to Accenture’s, banks are becoming the instrument of the scaling, export and increase in value of technology start-ups. There is every indication that banks are also winning with fintechs with regard to the regulation on regulatory technical standards (RTS) implementing the PSD2 recommendation, which has become the subject of guerrilla warfare between two competing parties within the EU institutions.

Not so long ago, 65 European fintechs, including the major ones such as Klarna, lodged a protest against the prohibition of access to customer data on the basis of screen scraping. They argued that this solution destroys the spirit of the PSD2 recommendation, because it makes fintech companies dependent on the banks’ APIs. These concerns were shared by the European Commissioner Valdis Dombrovskis, who appealed to the European Banking Authority (EBA) to soften its line.

In response, the European Federation of Banks called on the European Commission to keep the prohibition in place, citing the need to preserve high safety standards (70 per cent of surveyed banks express such concerns about the activity of start-ups). The final shape of the technical standards is yet to be decided. If they remain in their current form, that would mean a loss for the fintechs, not only in terms of prestige.

More and more banks, especially those digitally advanced, believe that after the implementation of the EU directive next year, they will hold all the cards in the competition for customers on the market, e.g. by aggregating their accounts with various operators. Such opinions were expressed by panelists representing PKO BP, Szymon Wałach (director of retail banking), and Pekao SA, Bartłomiej Nocoń (director of electronic banking), during the European Financial Congress in Sopot in June 2017. PKO BP also intends to create a platform integrating services of banks, fintechs, online providers and others. In the end, however, everything may be decided by the customers – according to surveys by PwC and DeNovo, 30 per cent of them intend to increase their use of products offered by the new players.

While expanding their cooperation, banks and fintechs have to hurry to find new areas of synergy. Both parties are increasingly aware that in the future Google, Amazon, and Facebook (already holding a European payment license), Apple, and even Starbucks will change the rules of the game in the financial sector, and many of today’s leading players could be, at best, relegated to the role of an application in an interface or a platform owned by these giants.