Tydzień w gospodarce

Category: Trendy gospodarcze

(Infographics Dariusz Gąszczyk)

The total fertility rate (TFR) in Poland is one of the lowest among all the countries in the world – according to the United Nations, Poland is ranked 189 out of 200 countries and dependent territories in this respect. The TFR in Poland is 1.31. Countries with fertility rates lower than Poland include Slovakia, Greece, Hungary, Spain, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Portugal, Moldova, Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong and Chinese Macau (the latter has a TFR of 1.19).

In recent years Belarus, which was in a demographic situation just as bad as Poland, has managed to increase its fertility rate from 1.3 to 1.6 (mainly by increasing expenditure on family benefits). Even China, which for decades prohibited its residents from having more than one child, has a TFR of 1.55.

Among European countries, the highest fertility rates are in France – 2 (but only 1.7 among the native French), Iceland – 1.96, as well as Sweden and the United Kingdom – 1.92.

Developed countries can be divided into two groups: those in which the TFR remains at a level above 1.7 and those where it does not exceed 1.5. There is a clear cultural difference between these groups of countries. The first group includes the Scandinavian countries, as well as all the English-speaking, French-speaking, and Dutch-speaking countries. The second group includes all the southern European countries, all the German-speaking countries and all the developed Asian countries. It is a division between countries where there is strong support for people with children, and those in which such support is missing. Other analyses show that these are mainly countries that do not necessarily have the highest level of wealth, but rather the highest quality of life measured by the HDI.

Unfortunately, Poland belongs to the second group in which the support is only now being developed.

In most of the other countries of Central and Eastern Europe which once belonged to this group, the fertility rate was lower than in the countries of Western and Southern Europe in this group – in 2004 the highest fertility rate was recorded in Estonia (1.47), while the lowest was found in Poland and the Czech Republic (1.23). In subsequent years, however, there was a significant increase in the birth rates in many countries. It was particularly noticeable in the Baltic countries and the countries of South-Eastern Europe (Slovenia, Croatia, Bulgaria, Romania). In recent years the fertility rate exceeded 1.5 in these countries. In the Czech Republic a significant increase in the TFR occurred in the years 2008-2010 – to the level of 1.51.

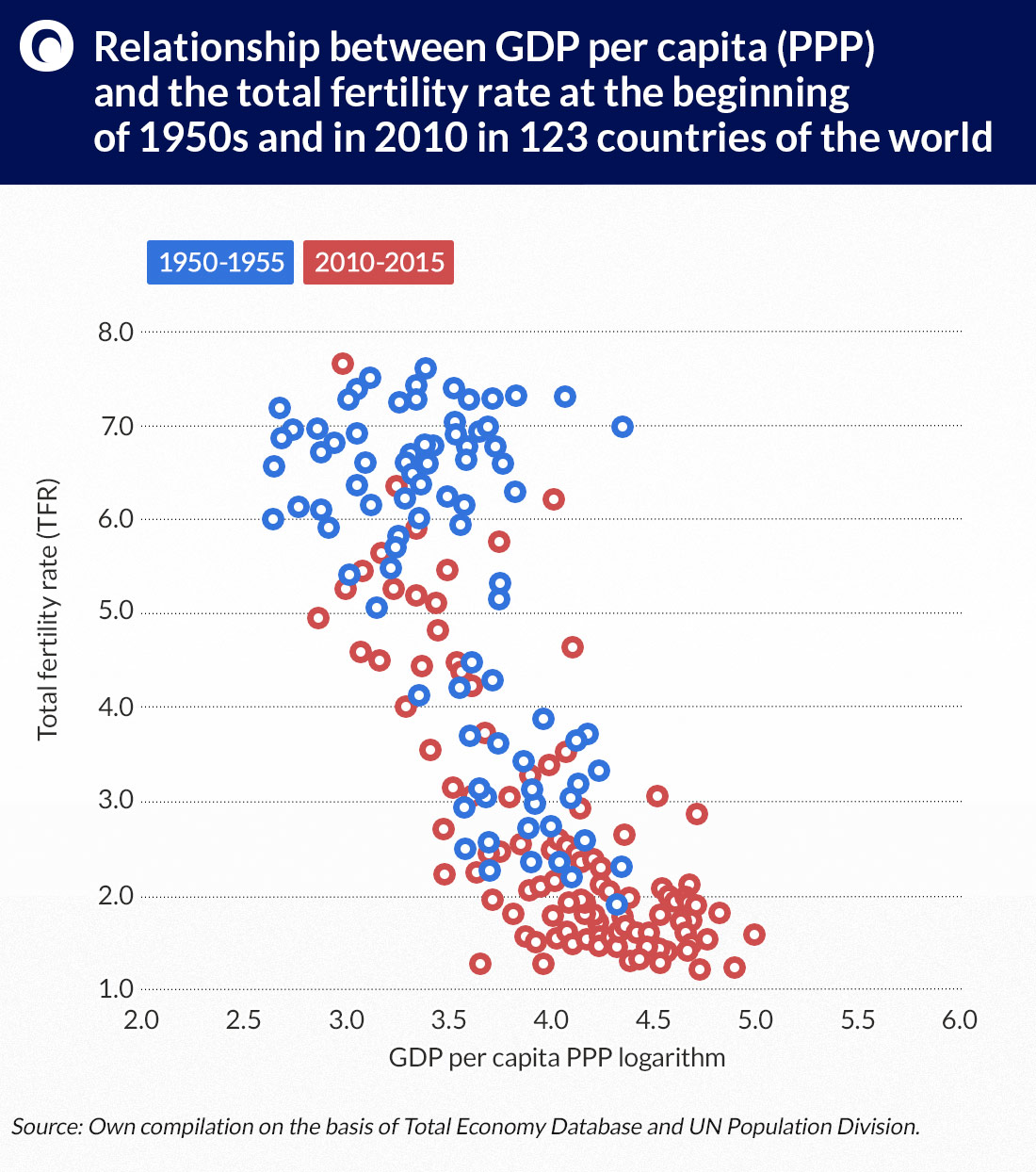

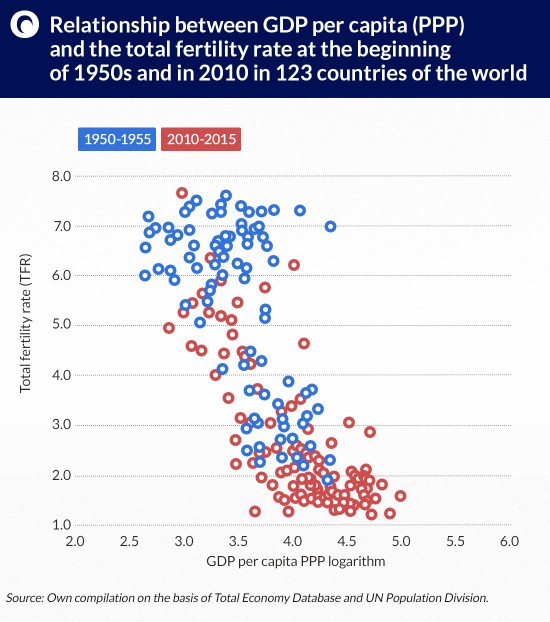

At least such is the conclusion of the economic and social history of the 19th and 20th centuries. Fertility decreases along with economic development and the increasing affluence of societies. This is associated with conscious family planning, the process of education and the growing aspirations of women. In the years 1950-1955, the global TFR amounted to nearly 5, i.e. there were five children per woman. Sixty years later this rate was already half that. It declined in every country and on every continent – in Africa from the astronomical figure of 6.6 to 4.7, and in Europe from the relatively high level of 2.7 down to 1.6. The biggest decline, however, was recorded in Asia, where the rate dropped from 5.8 to 2.2. The rate even dropped in the United States, despite the wave of immigrants bringing in family models from their countries of origin – in the 1950s the fertility rate in that country reached 3.3, and it currently stands at just 1.9.

(Infographics Dariusz Gąszczyk)

Fertility is also falling in Muslim countries. The statistical average is currently 3.7 children per mother. In the 1950s and 1960s the figure was 9 children, and in 1970 – 6.2. Even in this group, however, there are some countries where the fertility rates are similar to those of the West and are lower than 2.1, e.g. Saudi Arabia and Albania. The UN had to repeatedly revise fore-casts for Muslim countries, because the decline in the birth rates was higher than previously expected.

According to estimates for 2050, the fertility rate in these countries is expected to fall by another 38 percent. The same problems as in Europe and the developed countries – decreasing numbers of working age people and an aging population – will be emerging there.

Small families and old societies is the future of the world – the process is currently affecting Muslim countries, and will soon also spread to Africa. Poland is also following this well-known trend.

Over recent years, the fertility rate fell the least in Finland, Denmark, Sweden, Norway and the Netherlands. These countries recorded drops in the fertility rates in the 1950s, and after that their rates began growing. Why? They mainly owe this to the activities of the state. In turn, the main items on that list include higher female employment – mainly in the public sector, allowing women to work part-time; good access to childcare facilities and cash benefits, reducing the initial cost of having a child.

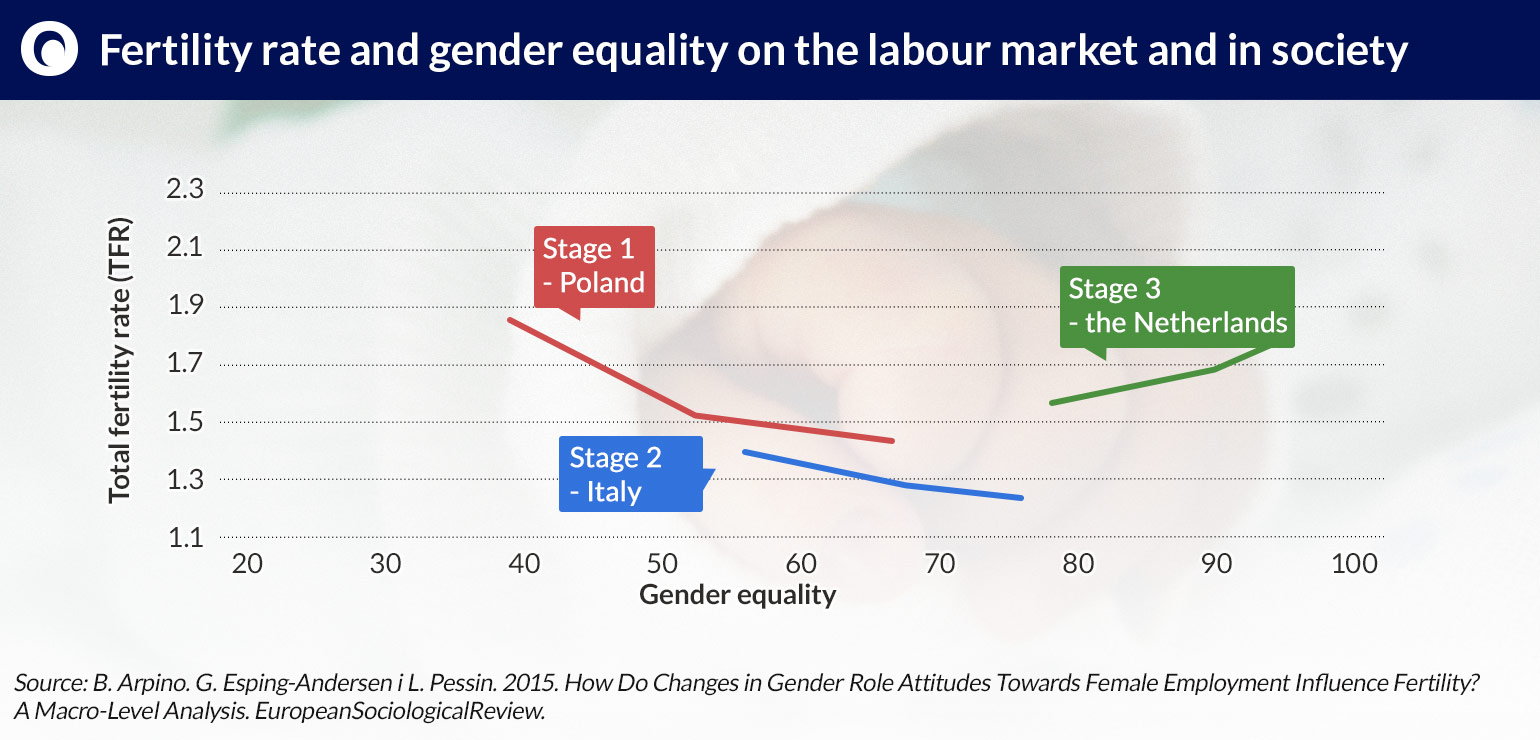

Poland seems to only be in the first stage of development of a family policy. As shown on the chart prepared by a renowned Danish sociologist Gosta Esping-Andersen, in the next stage we will have even lower fertility rates. That is unless policies which aim to make it easier to combine childrearing with professional roles prove successful, as for example in the Netherlands.

In Poland, only 33 per cent of women can negotiate the distribution of working time with their employer, while in the case of men the figure is 44 per cent. In the OECD countries, the differences in the ability to balance working time and family needs between men and women are not so great (44 and 41 per cent, respectively). Even in Turkey 41 per cent of women have the ability to determine their working time. This is also true for 47 per cent of women in Germany, 57 in Denmark, and more than 60 per cent in Sweden and the Netherlands. Moreover, in Luxembourg, Germany, Sweden and the Netherlands the percentage of women who can determine their working time is higher than for men.

The lack of bargaining power in relations with employers translates into rather low evaluation of the work-life balance by Poles. The average assessment of the possibility of balancing work and family time in Poland is 7.8 on a 10-point scale. In the majority of countries with a high TFR, the value of this ratio is higher – in France, Germany and Belgium – 7.9, in the Nether-lands and the United Kingdom – 8.1, in Sweden – 8.3, in Finland – 8.5, and in Denmark – as much as 8.6.

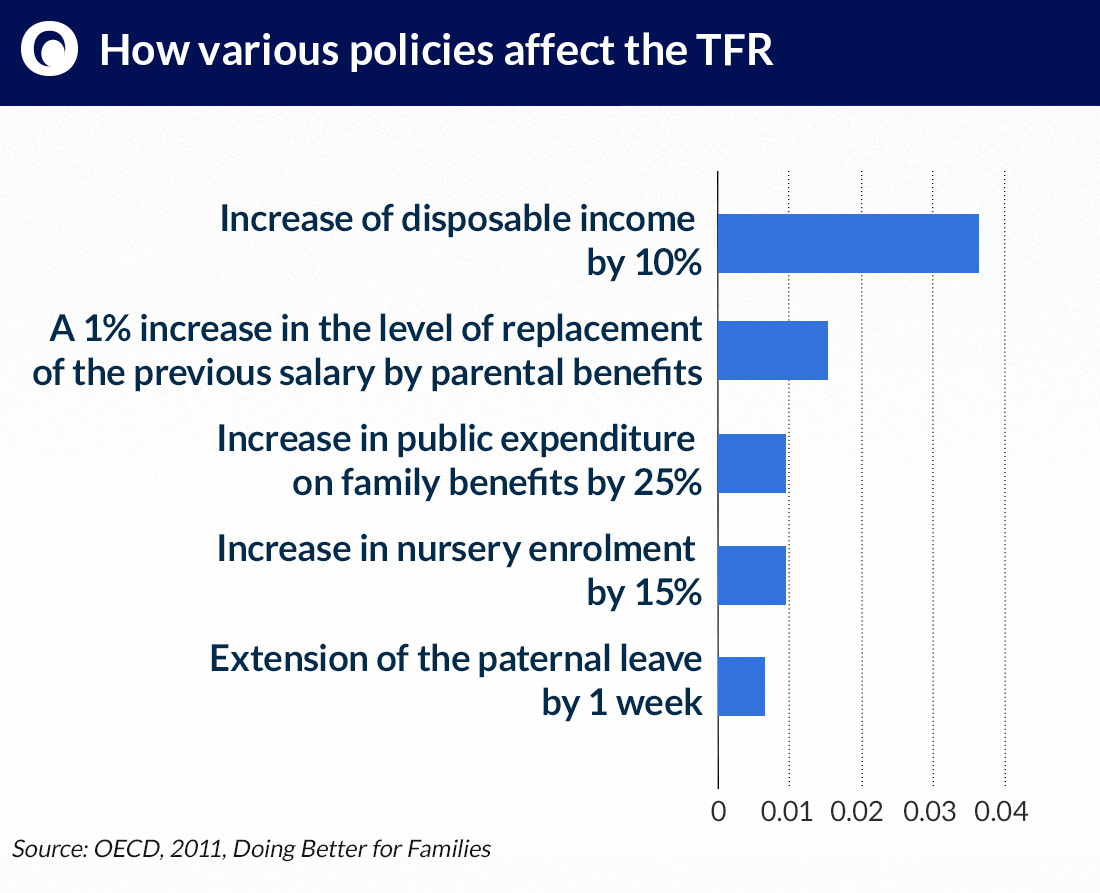

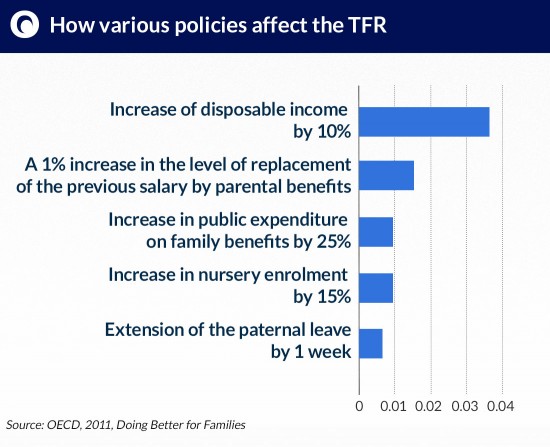

On a higher level of economic development it is necessary to make it easier for women to combine work with bringing up children, but also to guarantee social inclusion – that is the conclusion of Esping-Andersen’s work. There are also other policies that could be effective. In its analysis of the factors which have the biggest impact on the TFR and the number of births, the OECD compared the various policies implemented in developed countries and their effectiveness in shaping the TFR.

(Infographics Dariusz Gąszczyk)

It turns out that the most effective measures are monetary transfers increasing disposable income, although – as the analysts themselves point out – this was most often associated with deferred pregnancies that were „realized” at the moment when the changes introducing additional benefits came into force.

A similar phenomenon could occur in Poland if more couples try to take advantage of the new benefits. Higher parental benefits are also an important factor affecting the fertility rate. In accordance with the amendment of the Family Benefits Act, starting from 2016 every mother in Poland (whether unemployed or working pursuant to a contract for specific work) can receive pln1,000 for the period of parental leave.

The increase in total public expenditure is important, almost as much as increased enrolment in nurseries. Extended parental leave and childcare leave also have an impact, but their effect is the weakest of all the listed incentives.

The effects of the increases in family and childcare benefits in different countries are similar. Guy Laroque and Bernard Salani show that if France introduced an allowance of EUR150 (child benefits similar to the Polish 500+ program for the second and each subsequent child) it would be possible to obtain an increase in the fertility rate, but at the same time female labor participation would decline.

When the United Kingdom reformed the system of family benefits 20 years ago, it turned out that the unconditionally paid child benefits were also spent on alcohol and meeting the parents’ other needs rather than children’s. This does not mean, however, that families did not spend more on the needs of children, since the overall disposable income was higher.

In Russia, after benefits paid for the second child (USD11,000 per year) were introduced in 2007, the TFR increased by 0.15 and the number of households having „two and more” children also increased by 10 per cent.

Similar conclusions were also reached by economists from the Warsaw School of Economics. On the basis of a literature review conducted in 2012 they determined that benefits paid from the second child and the availability of nurseries allowing women to combine roles were the most effective measures.

What kind of support are Polish mothers expecting?

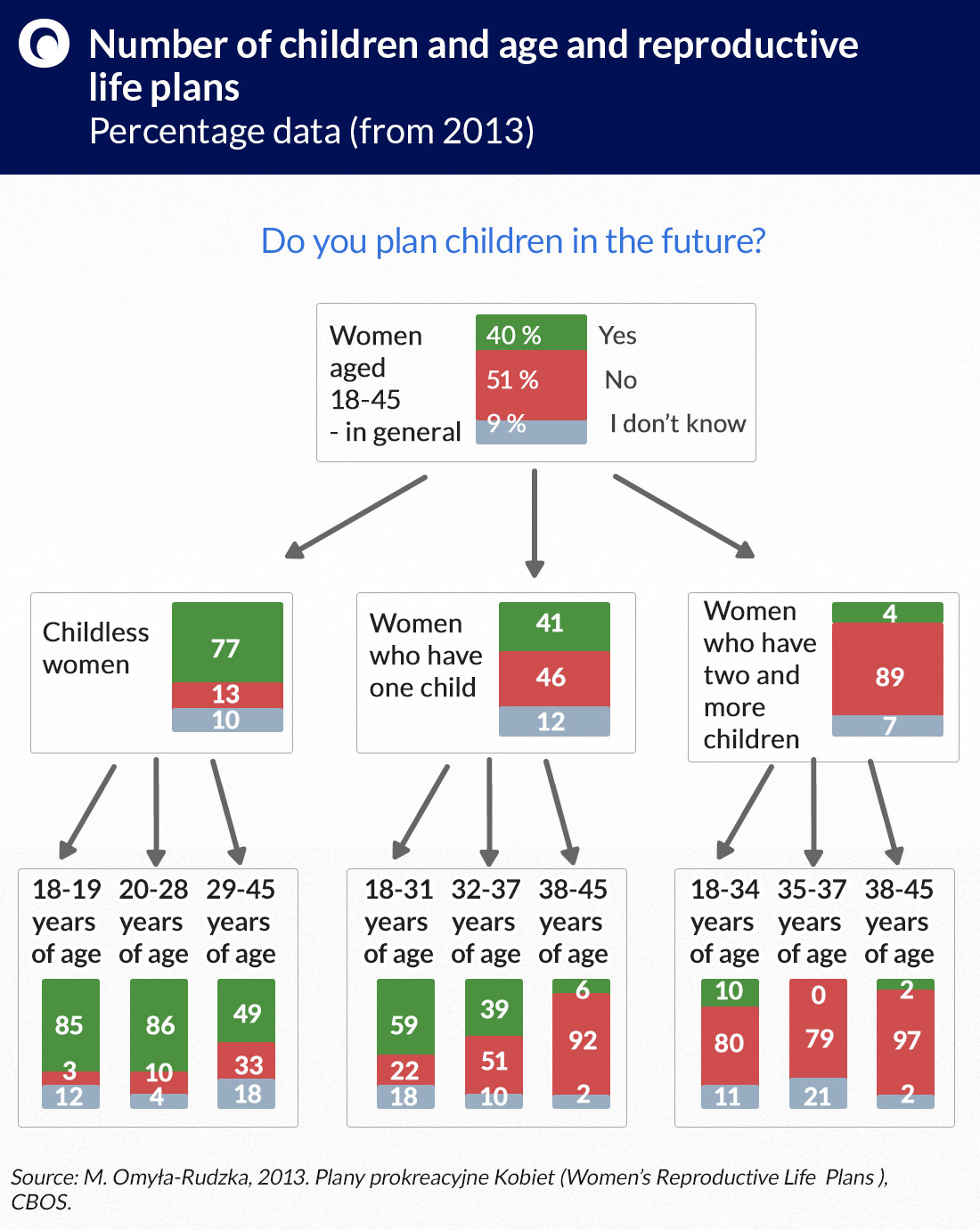

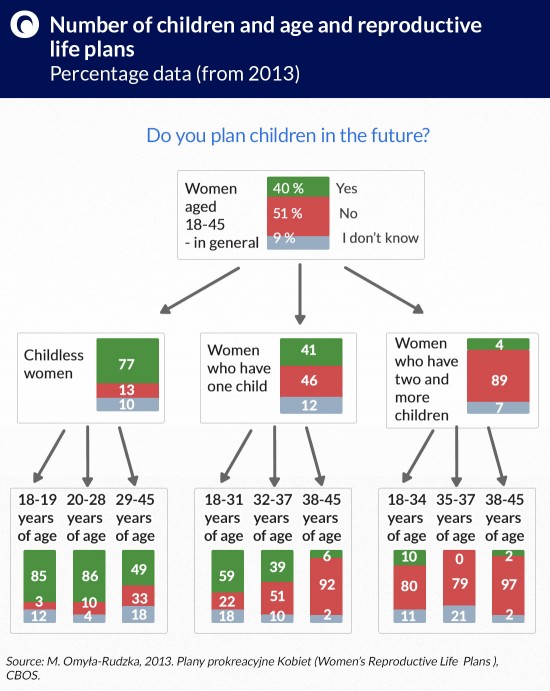

In Poland, there is statistically no problem with the desire to have one child – four out of five young childless Polish women want to have a baby. The situation is worse when it comes to having a second and subsequent children as this desire gradually decreases.

(Infographics Dariusz Gąszczyk)

Why don’t women want to have children? The CBOS asked this question and the most common response (56 per cent) among women aged 18-45 years was that they did not plan to have children because they had already fulfilled their procreation needs. This answer is naturally determined by the number of children they already have.

For a broad group of women the barrier to having children is their financial situation. The surveyed women most often replied that they could not afford to have another child (21 per cent), pointed to the lack of adequate housing conditions (8 per cent), and expressed fears of a decline in the standard of living (5 per cent). Every second woman aged 18-33 years who does not plan children (51 per cent), and one in five aged 34-45 years (20 per cent) will not have a (subsequent) child because of their financial situation.

According to the Social Diagnosis for 2015, some 2 million people could have a child, but are prevented from that, mainly by material conditions and the lack of support in childcare. For the most affluent people, the real issue lies not in genuine financial scarcity, but in aspirations and the desire to ensure a sufficiently high standard of living for the children.

22 per cent of women are convinced that they will not be able to reconcile professional responsibilities with child care; 13 per cent are afraid of losing their job as a result of pregnancy or after returning from maternity leave. Only 2 per cent believe that professional development is more important than having a child. In addition, 22 per cent simply do not want to have a child.

Responding to the question about the problems associated with providing care for their children, the women surveyed by the CBOS frequently pointed to the excessively high cost of employing a babysitter (61 per cent). Roughly every third surveyed mother mentioned in this context the lack of vacancies in nurseries or preschools (35 per cent), excessively high fees for such facilities (35 per cent) or the lack of someone in the family who could take care of the children (30 per cent). The women also reported problems involving the mismatch between the opening hours of childcare institutions and working hours (26 per cent), the lack of preschools or nurseries in their immediate neighborhood (22 per cent) and the lack of school day-care rooms (18 per cent).

Even at first glance, it is clear that what Polnad needs above all is material support raising the disposable income of families. That is why – also considering the experience of other countries – the 500+ program is a good solution. On the other hand, the thing that prevents Poland from reaching the fertility rates observed in the northern countries is mainly broadly defined gender equality, both at home and in the labor market. Changes in this area are the only way to ensure that Polish women will really want to give birth to more children.

I would like to thank Dr. Michał Brzeziński from the Faculty of Economic Sciences of the University of Warsaw for his help in the writing of this article.