Tydzień w gospodarce

Category: Trendy gospodarcze

(©Shutterstock)

(infographics: Darek Gąszczyk)

The EU Environment Council is one of the so-called sector councils. It consists the environment ministers from all the EU member states. During its last meeting, held in September 2015, the council voted to introduce the so-called Market Stability Reserve (MSR) from 2019. Originally this mechanism was planned to increase the prices of CO2 emission allowances (in the event that they were too low according to the European Commission) and was supposed to be launched in 2021. However, the supporters of this solution, including Germany, France and the United Kingdom, pressed to accelerate its introduction by four years, i.e. from 2017.

The introduction of the stability reserve from 2019 is therefore a compromise resulting from the opposition on the part of some EU member states, including Poland, to the proposed drastic acceleration of this reform. This compromise, however, still did not satisfy the opponents of the faster introduction of the MSR. During the last meeting of the EU Environment Council, six states voted against the introduction of the Market Stability Reserve in 2019: Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Poland, Romania and Hungary (it is worth noting that two Visegrad countries did not support us: Slovakia and the Czech Republic). This was not enough, however, to reject this solution, because at this level, decisions are taken by a majority vote.

The vote was the last decision-making step at the EU level in relation to this issue, which means that it is no longer possible to block the acceleration of this reform. The Polish government should be blamed for allowing itself to be outplayed by the EU bureaucrats. In what way? The very introduction of the MSR required a vote at the highest EU decision-making level, i.e. at the meeting of the European Council. There, individual EU countries are represented by their prime ministers, and the decisions are not adopted by a majority vote – the unanimous agreement of all states is required.

The European Council decided to introduce the Market Stability Reserve (in 2021) at one of its summits last year. Poland did not use its veto at that time. It was a mistake, because right after that the supporters of a „more ambitious” climate policy in the EU began pushing for the faster introduction of this mechanism. Their efforts proved successful, as the change of date was deemed to only constitute an amendment of the proposed reform of the EU emissions trading system. As a mere amendment, it no longer required the approval of the European Council, it was enough for the change to be adopted at a lower level – by the sectoral council, which makes decisions by a majority vote. We already know the final result.

What is the Market Stability Reserve? It is yet another method – after the so-called back-loading mechanism adopted two years ago – proposed by the EU authorities, aimed at a significant increase in the prices of CO2 emission allowances. It operates on a principle similar to an intervention purchase of cereals by the state. If emission allowances are too cheap according to Brussels, then some of them will be „removed” from the market in order to raise their prices.

Where did the idea for such a modification of the EU’s CO2 emissions trading system come from and what will be the implications of its introduction? This system is at the core of the European Union’s climate policy aimed at reducing the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. It was introduced in 2003 and covers over 10,000 of the most energy-intensive industrial plants in the EU, which consequently release the most carbon dioxide into the atmosphere (Poland accounts for over 800 such facilities). This mainly involves power plants and combined power and heating plants, but the „black list” also includes metal mills and glassworks, chemical plants, paper plants, lime factories, refineries, cement plants, tire factories, tile factories, bathtub factories, etc.

In the framework of the EU ETS (European Union Emissions Trading System), each of these establishments received a certain CO2 emission allowance for free from the pool allocated to the given country. If a company released into the atmosphere more gas than provided for by its allowance (limit), it had to pay for it by purchasing the right to additional emissions. Transactions could be carried out with those who had not used up their limit. Hence the word „trade” in the name of the system. The main objective of the adopted solution was for it to have at least to some extent a market character and for the European companies to be rewarded for reducing CO2 emissions (by investing in so-called low-emission and energy efficient technologies), because they could sell the unused part of the allowances at a profit or at least avoid paying for the „surplus” emissions. “This market nature of the EU ETS was also supposed to reduce the costs of the EU climate policy and render them more suited to the changing conditions”, recalls Konrad Szymański, a former MEP.

Since 2013, the plants covered by the EU ETS have been gradually losing their CO2 emission allowances that were previously allocated for free. This is done, on the one hand, in order to raise the price of those allowances on the emissions market, and on the other hand, to prepare the plants for paying for each tone of carbon dioxide emitted after 2020. The emission allowances are not only sold by those who have surpluses (in the new amended conditions this would not suffice to meet demand), but also – on special auctions – by government agencies of each country designated for that purpose. This change was supposed to increase the rate of reduction in CO2 emissions in the EU.

Along the way, however, something happened that completely surprised the architects and advocates of the EU climate policy. It was the economic crisis, which began in 2008. In many EU countries energy consumption began falling, mainly due to the drop in industrial production. As a consequence, the CO2 emissions also decreased. Because of this and, among others, because a number of energy producers and factories partly switched to low-emission or zero-emission technologies (the latter includes renewable energy sources), tens of industrial companies have recorded sizable surpluses instead of deficits in allowances for CO2 emissions. This resulted in the supply of CO2 emission allowances being much higher than the demand. In 2013 their surplus reached 1.5 billion tons and kept growing, which led to a dramatic fall in the prices of CO2 emission allowances. They decreased from 15 euro per ton in 2010 to 5 euro in 2013. Yet, according to the EU climate policy that price was supposed to continue to rise in order to make investments in low-emission or zero-emission technologies more viable.

As a result, the European Commission decided to reform the European Union’s system for the reduction of CO2 in the atmosphere. The goal is for the prices of CO2 emission allowances to start rising rapidly once again. This time, however, the EU authorities reached for bureaucratic measures, which have nothing to do with market mechanisms. The first one was so-called back-loading, or the suspension of some of the government auctions on which the rights to release carbon dioxide into the atmosphere were sold, shifting them to the years 2019-2020. This involved a total of 900 million tons, which was, however, still much less than the ever-increasing surplus of CO2 emission allowances. Therefore, their prices began to rise, but not at the rate expected by Brussels. As a result, the EU authorities have decided to reach for another administrative tool, which was named the Market Stability Reserve.

This mechanism is supposed to operate in a similar way as the intervention purchases of cereals by the state when their price is too low. That is, if the price of CO2 emissions falls below a level desired by Brussels, then some of the allowances intended for sale are withdrawn from the government auctions. They are returned on the auctions only after the price of such allowances has reached the expected level.

That is not all, however, because the emission allowances for 900 million tonnes of C02, suspended under the back-loading mechanism, will also go to the Market Stability Reserve. At the time when they were suspended, these allowances were supposed to be returned to the market. Such a decision means de facto a higher reduction in CO2 emissions by 2020 than what the member states agreed on when signing the climate and energy package in 2008.

(infographics: Darek Gąszczyk)

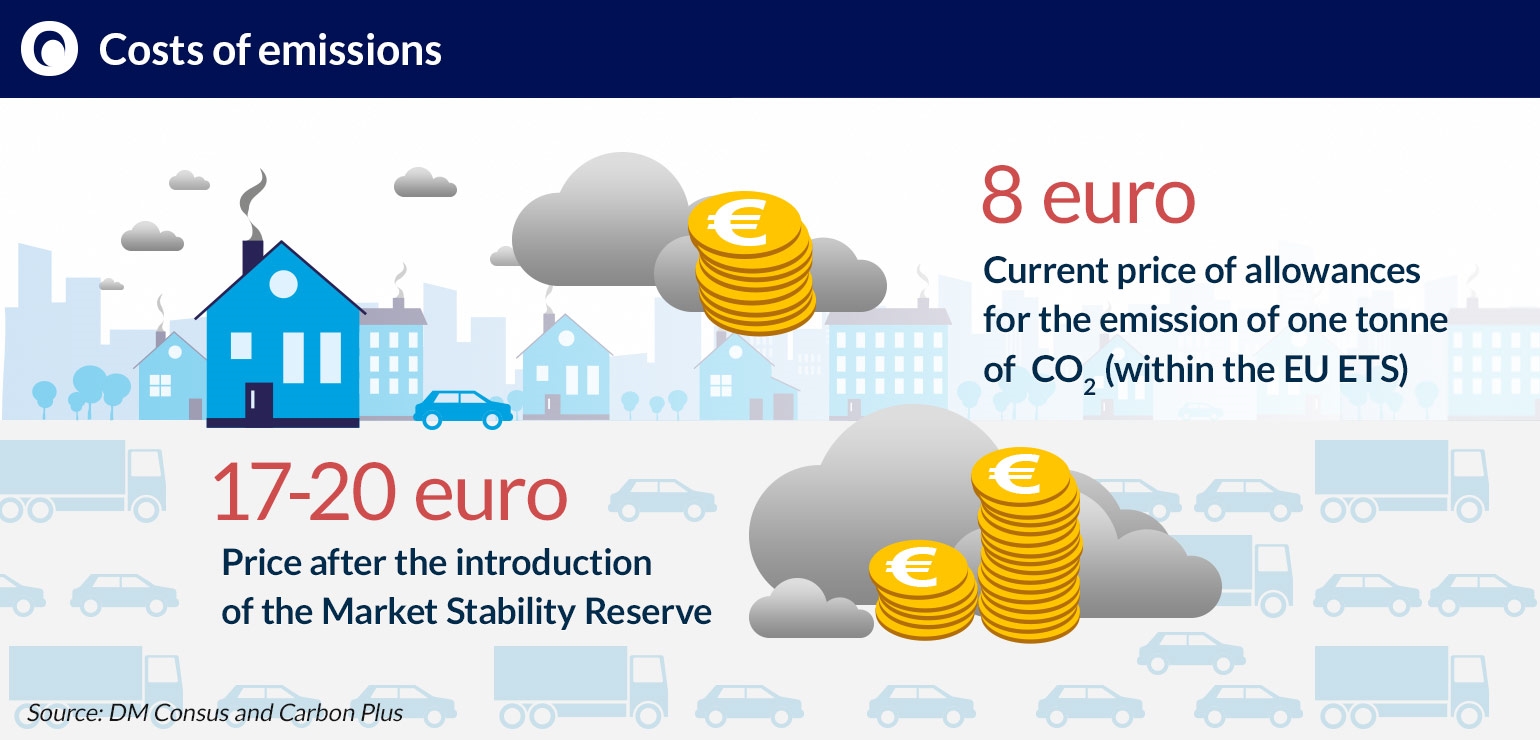

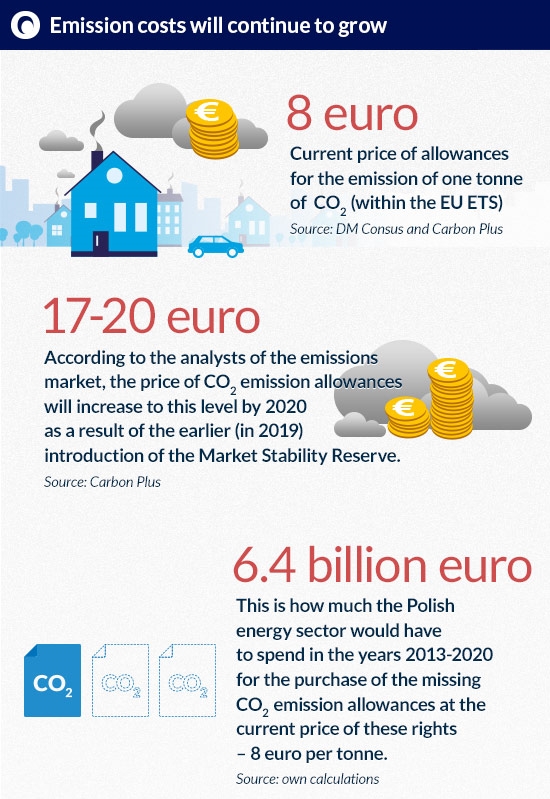

What will be the consequences? First of all, Poland risks a rapid increase in the prices of CO2 emission permits, which will impact Poland most acutely, as its energy sector is more coal-based than of any other EU country. Higher prices of these allowances mean higher energy prices, which will affect not only the consumers, but also Polish companies, by reducing their competitiveness. According to analysts of the emissions trading market, among others, from Carbon Plus, as a result of the earlier introduction of the Market Stability Reserve (in 2019), the price of CO2 emission allowances will have increased to the level of EUR17-20 by 2020. They currently cost less than half of that – EUR8.

Polish coal-fired power plants already have to buy CO2 emission allowances and by 2020 they will have to buy even more of them. For example: Polska Grupa Energetyczna (Polish Energy Group), the largest Polish producer of electricity, will have to purchase almost half of the necessary rights for carbon dioxide emissions this year (the rest are „free” allowances) and in the years 2013-2020, this ratio will reach an annual average of 65 per cent. The entire energy sector in Poland will be in a similar situation.

Let us translate that into actual costs. In the years 2013-2020, the Polish energy industry will have to buy additional allowances for the emission of about 800 million tons of carbon dioxide. At the current price of 8 euro per ton, this means an expense of 6.4 billion euro. However, in 2019 the price of these allowances is supposed to sharply increase due to the introduction of the Market Stability Reserve. Which means that these costs will be much higher than EUR6.4bn. Electricity producers will try to include them in the sales prices. For the time being, it is difficult to estimate how much electric energy prices will rise by as a result. But it will be a significant increase, given that today ecological para-taxes (including subsidies for renewable energy) and excise duty make up more than half of the wholesale price of electricity in our country.

There will also be geopolitical implications. Due to the EU’s climate policy, Polish energy companies are already building a number of gas power plants and gas-fired blocks in order to replace the coal-fired boilers. The reason is that gas generates half the emissions of coal (this means that its combustion is accompanied by lower CO2 emissions). In the absence of an increase in domestic gas extraction (which is not likely for now) and with the high prices of the fuel supplied by the gas terminal in Świnoujście (more expensive than Russian), this will mean an increase in purchases from Gazprom. We are therefore threatened with greater dependence on supplies from Russia than today, which seems neither beneficial nor safe for our country.