Tydzień w gospodarce

Category: Trendy gospodarcze

(Tetyana Pryymak, CC BY-ND)

Although there is no chance of obtaining a fertility rate that guarantees the replacement of generations, the government could take many steps to encourage citizens to reproduce.

The principles of the 500+ program are relatively simple: a childcare benefit for the second and subsequent children under 18 years of age in the amount of PLN500 net per month. Less affluent families will also be entitled to receive the benefit for the first or only child, provided that the income of the family does not exceed PLN800 per person (PLN1,200 if there is a disabled child in the family).

The benefit payments are supposed to begin in April, and will probably be handled by social welfare offices. Municipalities, however, were given three months to launch the system. In 2016, the program is expected to cost PLN 17.3 billion. After three years the Ministry of Family will have to verify the benefit amount and introduce indexation of the funds.

The income obtained from this benefit will not be taxed and will also not result in restrictions on the payment of any other type of allowances such as family benefits or social welfare allowances.

This year has already brought other changes in family policy. If a family taking advantage of benefits exceeds an income, it will not lose the payment, but will see the benefits reduced by the amount exceeding the criterion. The „PLN for PLN” mechanism is supposed to encourage people to take up work without the fear of losing benefits. Thanks to this, exceeding the income threshold entitling a family to benefits (PLN674 per person in the family) will not automatically result in the loss of the benefits. Previously, it was enough to exceed the threshold by even PLN1 in order to lose all benefits. The parental benefits are low — the total amount of the seven types of payments available is several hundred PLN; they are merely an addition to the welfare aimed at the poor.

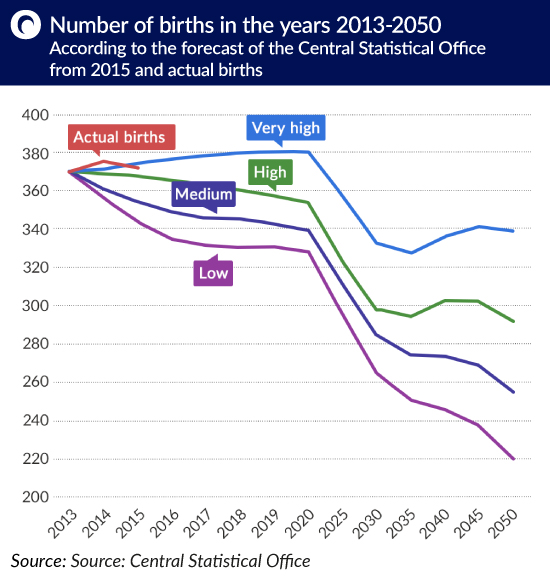

The government assumes that the 500+ program will result in an optimistic birth-rate scenario, using a calculation made by the Central Statistical Office in 2014. This so-called “high” scenario assumes that in 2015-2050 an annual average of 14 percent more children will be born in Poland compared to the medium scenario. Interestingly, in 2014 some 375,000 children were born — about 4,000 more than in the CSO’s most optimistic scenario. In 2015, however, 372,000 children were born, which is about 2,000 fewer than in the very high scenario. So far, the medium scenario seems the most realistic.

Poland has no chance of reaching a total fertility rate (TFR, the number of children per woman in the childbearing age of 16 to 49) of 2.1, which guarantees the re-placement of generations.

(infographics Zbigniew Makowski)

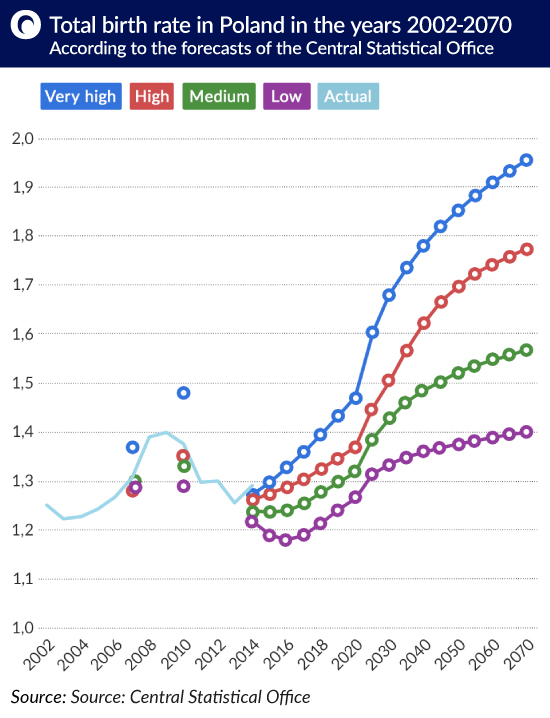

Under the very high scenario, by 2025 Poland’s fertility rate would reach 1.6. According to the low scenario it would have a TFR of 1.3, according to the medium scenario — 1.38, and according to the high scenario — 1.44.

Central Statistical Office estimates from previous years show that while its estimates may be a little off, it has correctly predicted the direction of change. AS well, the CSO did not take into account changes in family policy which will probably result in more births.

This all means that the fertility rate in Poland will likely increase, but only slightly.

(infographics Zbigniew Makowski)

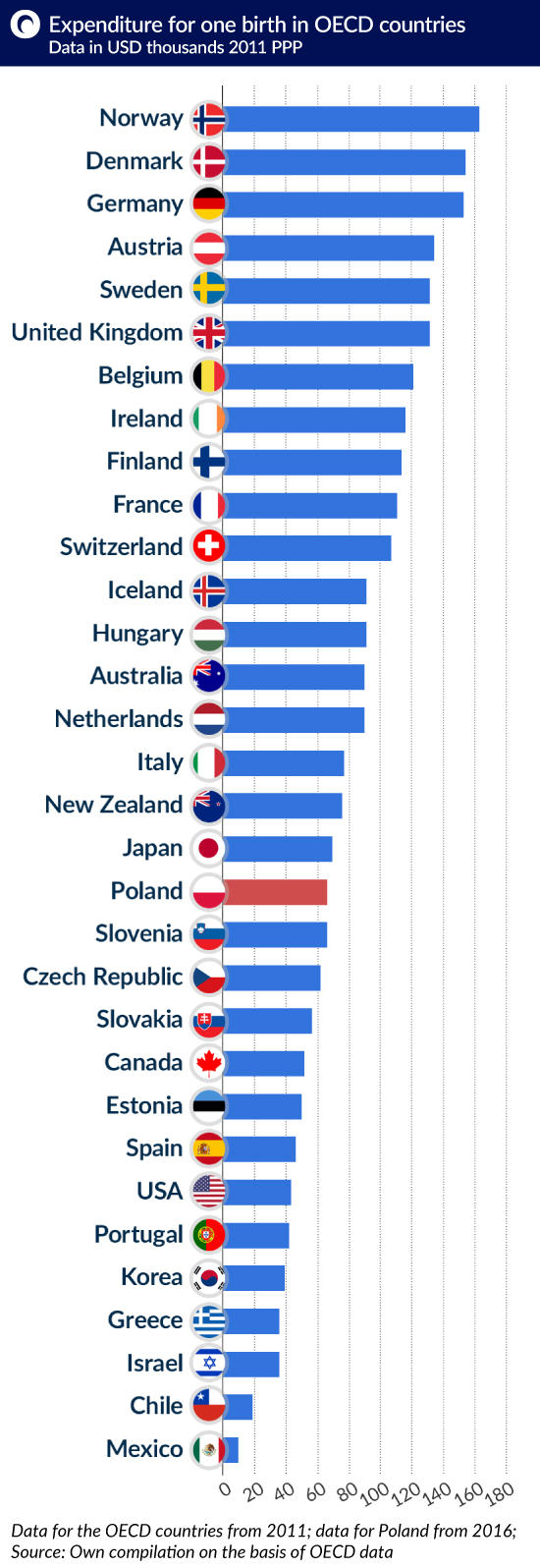

According to the most recent available OECD data, Poland spent 1.8 per cent of GDP on family policy, i.e. family benefits, tax breaks, etc. The average level of expenditure across the OECD was 2.5 per cent of GDP. In the countries with the highest TFR spending came to about 4 per cent of GDP (4.3 per cent in the United Kingdom, 4.1 per cent in Denmark, 4 per cent in Ireland, 3.6 per cent in France and 3.2 per cent in Norway). If the data is updated to take into account plans for 2016, Poland reaches about 2.9-3.0 per cent of GDP, similar to Germany, Finland, and Norway.

A very basic way to assess family policies is to calculate the total expenditure per one birth, which in Poland (before the changes in family policy) in 2011 reached about USD41,000. That would mean Poland invests more or less as much as the US, Portugal, Korea, and Spain in the fertility rate.

After the changes (also taking into account the higher level of births resulting from the Central Statistical Office’s very high scenario in 2016) this translates into approximately USD66,000 spent on every child born. However, the expenditure in Poland is still less than half that of Norway, Denmark, Germany, and Sweden (over USD150,000).

The increase in expenditure in the framework of the 500+ program will there-fore still not match spending in other countries. The system used in the Nether-lands seems to be the most effective, amounting to USD90,000 for every child, and at the same time it is a country with a high TFR.

(infographics Zbigniew Makowski)

Until now, Polish family benefits have been low – the maximum amounted to 3 per cent of the average wage, whereas in OECD countries the average was 4 per cent. New Zealand, the UK and Slovenia have the highest benefits reaching 8-9 per cent of the average wage. They are also high in Ireland and Australia, where they amount to 7 per cent of the average salary. Benefits reach 2 per cent in the United States and Norway, while in Sweden family benefits only amount to 3 per cent of the average wage. The lowest benefits are found in Spain, Estonia, France and Israel where they only amount to 1-2 per cent of the average wage.

PwC carried out an experiment, analyzing the support that a hypothetical family with two children could count on in different EU countries. Poland was ranked the fifth from the bottom — the model family could count on the equivalent of EUR530 per year. The only countries ranked lower were Greece, Lithuania, Romania and Bulgaria. In the last two countries, state assistance is purely symbolic, amounting to EUR38 and EU 20 per year, respectively. The average support in the EU amounts to EUR2,300. Luxembourg, which supports the model 2+2 family with support of EUR9,200, is the most generous. France and Germany are ranked next — with EUR6,700 and EUR4,800, respectively. Taking the percentage share of state support in relation to the parents’ average salary, France is in the lead — 13.7 per cent, followed by Slovenia — 12.7 per cent, and Hungary — 9.6 per cent. In Poland the figure is 2.4 per cent.

Poland has long parental leave but looking at the policy’s impact on Poland’s low fertility rate, the system may be too generous. In 2013, only 9.6 per cent of Polish children up to two years old were enrolled in nurseries. The OECD average was 31 per cent. Only Mexico, the Czech Republic and Slovakia had fewer children enrolled in nurseries than Poland. In the United States 28 per cent of families, and in the United Kingdom 35 per cent of families take advantage of this form of support. The figures are the highest in countries with a high TFR — 47 per cent in Sweden, close to half in France, and about 55 per cent in Norway and the Netherlands. The number of children in nurseries in Den-mark is even higher — 67 per cent.

The percentage of children in Poland enrolled in preschools is higher. In 2013, 69 per cent of children aged 4-5 years were in preschool. This should rise after an increase in grants for local governments in 2014-2015.

On average in OECD countries, 81 per cent of children were enrolled in preschools. In Estonia, Hungary, and Mexico nearly 90 per cent were, in Sweden — 94 per cent, in Norway — 97 per cent, and close to 100 per cent in France. On the other hand, in the United States and Canada, the figures were 66 per cent and 46 per cent, respectively.

Poland’s preschool enrolment levels mean that the professional activity of women with children under two years of age is relatively low. Only 54 per cent of women aged 18-64 years with small children worked. In Russia, 63 per cent did, while in Lithuania 71 per cent, and in the Netherlands and Denmark more than 75 worked. In France 61 per cent of women with young children worked. However, in the United Kingdom only 58 per cent and in the United States only 56 per cent of mothers worked. The figures were much lower in the Czech Republic, where only 20 per cent worked, in Slovakia — 15 per cent, and in Hungary — just 12 per cent.

In those countries, however, mothers return to the labor market once their children get a bit older. Among mothers with children aged 3-5 years, 70 per cent of Czech women, 74 per cent of French women and four-fifths of Dutch, Finnish, Estonian, Danish, Slovakian and Russian women worked. In Poland the percentage of women returning to work several years after having a child is 65 per cent. It is higher than in the USA — 62 per cent, or in the United Kingdom — 63 per cent, but still much lower than in other leading countries.

For the time being, the tax system does not support families in Poland. Tax preferences for families with children are modest. The tax wedge for a married couple with two children is about 3.4 percentage points lower than that of a childless family, which ranks Poland 24th among developed countries. In OECD countries this difference reaches an average of 4.4 percentage points.

The most pro-family tax systems are found in Hungary (a difference of 10.9 percentage points in favor of families with children), Slovenia (9.5 percentage points), Luxembourg (9.2 percentage points) and the Czech Republic (7.5 percentage points). In Turkey the difference is only 0.7 percentage points, in Spain 1.1 percentage points and in Korea 1.4 percentage points. Families do not get any ad-vantage in Greece and Mexico.

The construction of the tax wedge in Poland means that the richest families get the greatest benefit. Every third Polish family with two children earns too little to fully utilize existing personal income tax breaks. In 2013, 63 per cent of families fully used the tax credit for one child, 60.3 per cent — for two children, 41.3 per cent — for three children, and only a quarter for four and more children.

Poland also has one of the highest levels in the OECD of taxation and social security contributions (29.6% per cent) applied to low-income workers. Poland is behind seven developed countries, while the average for the OECD is 17.9 per cent. In Ireland, New Zealand, Canada and Australia the tax wedge for single parents is negative, which means they receive cash benefits from the state.

Under a moderately optimistic assumption, the new benefit may increase the number of births in Poland by 10-15 per cent (based on the experience of other countries with similar reforms).

There is an additional advantage that legislation introducing the PLN500 benefit has a built-in evaluation system, as it might make sense to simplify Polish family policy which could result in more births.

First, after the introduction of the almost universal PLN500 benefit, it may be worth unifying all types of child-related benefits and allowances (of which there are seven), while also introducing a maximum qualifying income threshold. A number of developed countries have similar systems. The downside of introducing a maximum threshold is the cost of income verification, however, it could be solved by authorizing the Social Insurance Institution to check contributions paid in previous years. Technology could make that simple and cheap.

An additional advantage would be the simplicity of the system, which would need fewer bureaucrats to administer — family benefits are currently handled by over 8,000 people — as well as fewer court disputes with inconsistent interpretations, and a lower burden placed on parents applying for support (e.g. the necessity of collecting the relevant documents).

Second, Poland should consider when the benefits should be paid out. Under the current rules, for the first year after a child’s birth insured people receive 80 per cent of their salary (no less than PLN1,000 a month) from the Social Insurance Institution. The uninsured (farmers, students, the unemployed, people working under special contracts) receive an allowance of PLN1,000. It is worth considering that the PLN500 allowance be combined with those benefits, which create fewer types of benefits, making it easier for parents to apply (as is the case in the United Kingdom).

Third, Poland should build nurseries. Poland is currently positioned somewhere between the paternalistic South, where mothers stay at home, and the „gender equal” North, where there are institutions supporting childcare. The countries of the North are coping much better with the demographic crisis, so it’s probably worth following their example. Poland could introduce tax breaks for employers who set up workplace nurseries or build them together with other companies.

Fourth, Poland should reform the tax wedge by reducing it for poor people raising children, and slightly increasing for higher earners, especially those without children. This could be done through a degressive tax-free amount of PLN500 minus 20 per cent of the obtained income.

Fifth, labor laws should be made more flexible to make it easier to shape the relationship between employees and employers.

Poland already has a family policy — it is simply time to sort it out.