Tydzień w gospodarce

Category: Trendy gospodarcze

Migration has always been a favourite activity of Homo sapiens. It is supposed that modern humans came from East Africa, and were able to settle in all continents suitable for living. Migration, and thus the mixing of peoples and of various achievements and experiences is the essence of prehistoric civilisations that were the foundation of the Greco-Roman civilisation – the one from which we drew and continue to draw on.

Guarded borders and national unitary states are quite recent inventions of humanity. Passports, as commonly used documents enabling the crossing of borders, and above all, leaving one’s own country, are an invention from only 100 years ago. Although experts trace back the history of passports to a document issued approx. 2,500 years ago by King Artaxerxes I of Persia, the document was not a permit for the king’s cupbearer Nahemiah to travel, but was rather an order for the viceroys of lands beyond the Euphrates to ensure his safety during his journey to Jerusalem to rebuild its walls.

Like in the ancient times, the most precious, but not always present, value in the modern Western world is freedom, including the freedom to move around the world and choose the place of residence. In the European Union, the right to travel and settle outside the country of birth has become a standard. For the Europeans experiencing the simplicity and convenience of the Schengen rules, their abolition would be unbearable.

Migrations, however, are not always so pleasant. Many peoples perished in massacres when more efficient and better equipped ones embarked on the conquest of new lands, whether locally or overseas. Had they survived and kept their tribal-national identity, the Yotvingians, Prussians, Guanches, Incas, Aztecs and Mayans would have had something to say about this…

Therefore, today’s anxieties and fears associated with migrations have their well-established historical background. It is easy to spread visions of dangers arising from the influx of “foreigners” against this background. In France, a new book by Michel Houellebecq has just been published. France in 2022 is an Islamised country, whose universities are required to teach the Koran and polygamy is allowed. The aversion to foreigners has been gradually growing in many countries of the Union, and the reason is not just terrorism on the part of a radicalised handful of indoctrinated Muslims, but primarily concerns related to the primitively understood economic interest of the so-called native citizens, among which, paradoxically, there are many descendants of immigrants.

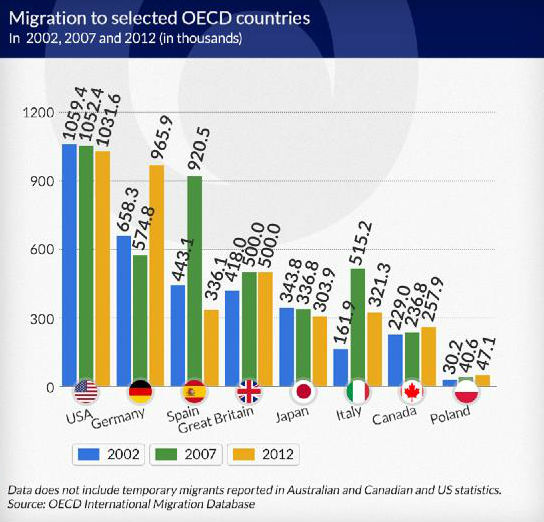

At the turn of the century there were approx. 75 million people born outside the country of their residence in the OECD countries. Until 2013, their number increased to approx. 115 million. In 2012 alone, the number of permanent immigrants to the OECD area was 4 million, half of whom settled in the European member states of the organisation.

A steady stream of foreigners coming to the OECD countries was observed about 50 years ago. The post-war relaxation of rigours between countries and the beginning of the economic boom in Western Europe and Japan were conducive to this process. The magnitude of immigration to the OECD underwent considerable fluctuations, but it is an upward trend. It lacks explosive energy and is a slow, yet steady, increase.

In 2010, immigration inflows to OECD countries were about one third larger than in 2000. Peak migration occurred in 2007, followed by a marked decrease in numbers in the two subsequent years. If we assign the value of 100 to the inflow of immigrants to the OECD in 2000, the ratio amounted to just over 150 in 2007, followed by a decrease to about 130-140 in the subsequent years.

The impact of the economic situation on the intensity of migration is very clear. There are examples to prove it. Before the crisis, Spain took full advantage of the careless generosity of the European Union. This has made it a land of milk and honey, except that it was attributed mainly to grants and borrowed money. Therefore, the prosperous Iberian hive attracted larger and larger waves of immigrants. In the period 2000-2007 their influx tripled. In the following years, the crisis caused the influx to amount to only one-third of the peak value.

At the other extreme is solid, hard-working and frugal Germany, which in 2012 became the second largest destination in the OECD for immigration after the United States. Germany attracts with its prosperity, diversified economy that offers a multitude of jobs in various professions and specialisations, and its unparalleled tolerance for “aliens”. Tolerance is meant here in relative terms, because even drastic examples of xenophobia in Germany are not rare.

There are people who, leaving economic interests out of the discussion, see the sources of Germany’s predominant hospitality in the mechanism of redemption for war crimes, but proving this thesis beyond doubt is rather impossible. In any case, the governments of the Federal Republic of Germany have consistently supported the principle of free movement of people, including the so-called workforce. The practical choice by future immigrants is mainly influenced by economic considerations based on social benefits, and the views and attitudes of Germans towards foreigners is a less important factor.

Contemporary migrations can be described with hundreds and thousands of figures and indicators, but the statistical overload blurs the image rather than making it clearer. Extensive data for those interested in the details are included primarily in the OECD report entitled “International Migration Outlook 2014”. The picture we present will be completed with information strengthening the thesis of income and economic factors as the main driving force behind migration.

Affluent people and people satisfied with their lives rarely decide to leave the country of their birth for good. It is one of the reasons for the lack of success of the plan to attract highly qualified specialists from outside the EU to Germany. During less than two years (January 2013 – September 2014) only approx. 20,000 foreigners benefited from the regulations governing the issue of the so-called blue card for people with degrees, of which more than half are people previously living in Germany.

Therefore, mostly people looking to change their current bad situation emigrate, and much less those who are already in a good or very good situation and want to improve it even further. In 2012, more than 10% of all emigration flows were attributed to still poor China, from which slightly more than half a million people emigrated. GDP per capita measured in comparable values (PPP) in China was USD 11,900 in 2013. Next was Romania (5.6%) and Poland (5.4%). GDP per capita in Romania in 2013 was USD 19,000, in Poland – USD 23600, while in Germany – USD 44,500 and in Great Britain – USD 38,500 (according to World Bank data).

Noteworthy is the information that despite the effects of the crisis, which are still felt, most immigrants work. When it comes to people with poor education, the average percentage of employed persons is higher among immigrants (54.1%) than among people born in a given country (52.6%). Foreigners who came from poorer countries are simply more determined than the native beneficiaries of the welfare state. This conclusion is also confirmed by the fact that the employed immigrants are 50% more likely to be overqualified for their positions.

The determination of immigrants causes strong resistance of the „locals”, which translates into a politically motivated attempt to close the Western countries for foreigners, even if they are EU citizens. Examples that first come to mind are the actions of the British Prime Minister David Cameron, the anti-immigrant (and at the same racist) laws enacted in Arizona in 2010 and the recent emergence of the anti-Islamic Pegida movement in the territory of the former GDR.

The division into the rich North attracting immigrants from the rest of the EU and the poor South (in addition, exposed to waves of refugees from the other side of the Mediterranean), and even poorer East, which are sources of immigrants, clearly manifests itself in the European Union.

On a side note, as a warning, it is worth noting that nationalist sentiments and movements such as the latest emanation in the form of Pegida or the slightly older Hungarian Jobbik, spread more easily in ethnically and linguistically uniform countries or areas.

Hotheads seeking immediate solutions to social sentiment and political problems choose not to see that overall, countries gain more than lose from having foreigners come to them. Although in the long run, due to the progressing automation, robotisation and computerisation, the demand for labour expressed by the number of persons needed for work will inevitably decline, the extensive growth model in which GDP grows (or is expected to grow) together with greater employment still dominates today.

When considering migrations in this context, one must note that in the last decade, immigrants in the United States accounted for 47% of labour force growth, and in Europe they filled up to 70% of new or restored jobs. Immigrants fuel all sectors – the most modern and the declining ones. This is because today’s young immigrants (the same as young locals) are better educated than the retiring immigrants. Where the structure is dominated by young immigrants, in total immigrants bring more to the public pockets in taxes and social security contributions than they receive in the form of social benefits. Contrary to popular prejudice, young uneducated immigrants get less from the state than the native youth of the same educational status. Migration also allows to slow down the aging process of the total workforce which is troubling the majority of OECD countries, including Poland.

Since the days of the early American colonists, but also from the example of Australian criminal exiles, it is evident that migrations generally contribute not only to growth but also to economic development. The share of well and very well-educated immigrants in the number of foreigners settling in the OECD is clearly increasing. The number of immigrants to the OECD with higher education has increased during the first decade of this century by about 70%, reaching nearly 30 million people in 2010/2011. The stream of people with degrees is supplied primarily by Asians.

Writer and screenwriter Andrzej Mularczyk recalls his strolls through Warsaw just after the war, where among the rubble, in a pub at Marszałkowska 8 he saw something extraordinary – a black man playing a drum. A lot of that consternation remains in Poland today. The reason is of a historical nature – centuries of isolation from the centres of civilisation development. Under occupations, Poles lived in the peripheral and poorest (with the exception of the Kingdom of Poland) outskirts of their metropolises, where hardly any „alien” had any interest to come, and if any came – he was one of the occupants, and therefore an enemy. You can summarise the years of the Second Polish Republic and the Polish People’s Republic in a similar way. Soon it may and certainly will be different.

Due to immigration and the weak natural increase characteristic of nations with noticeable achievements , the number of Poles is and will be diminishing. There is no reason to despair, because this means more space and fresh air for those left. Moreover, it is time to stop cultivating the extensive growth model based on crowds ready to dig ditches and push millions of wheelbarrows.

Fundamental changes require time, so possible shortages of workers with specific skills during the transition period may be overcome by encouraging foreigners to settle in. Aid and humanitarian considerations constitute a vast, but quite a separate topic. An example of how to control the influx of foreigners purposefully and with self-interest may be taken from Canada.

For years Canada has been keeping the door open for immigrants, which makes the influx of foreigners per capita the highest in the world, but admission is regulated. Limits to immigration apply. Interestingly, the right-wing (!) government in Ottawa has recently raised the ceiling of 265,000 to 285,000 people per year. Since 1967, the prospective immigrant has had to face a scoring system there that rewards education, fluent knowledge of English or French, professional experience and youth (in the age category the twenty-year-olds are assigned maximum points).

The result is that despite the difficult times, the population is growing rapidly – according to the 2011 census, Canada had 33.5 million inhabitants, and between 1990 and 2008 its population increased by 5.6 million, i.e. by one-fifth. Regulating the inflow of foreigners and limiting access for people with minimum qualifications did not provide protection against such phenomena as employing newly-arrived doctors as taxi drivers or firing native Canadians and recruiting immigrants who accept lower wages. The unemployment rate among immigrants is almost 50% higher than among people born in Canada. Therefore, it must be remembered that there are no ideal systems and rules.

Since 1 January 2015, a new system called “Express Entry” has been in effect in Canada, which rewards immigrants with offers of a specific job. If the total number of points that may be awarded is 1200, then as many as 600 points are awarded for a document certifying the will to employ the potential newcomer. This creates instances of fraud and abuse, but it is unfortunately inevitable, because the thinking man never abandons attempts to improve his position and… cheat his fellow men.

In the foreseeable future, Poland will certainly not be a destination country of large immigration, but a large inflow of other people, not as homespun as we are, would be very good for Poland.

| If you are looking for more information about migration from and to CEE countries, we would like to call your attention to the latest English language issue of our Spot On Magazine, featuring some of central Europe’s best writers and economists.

Spot On Magazine is a monthly publication, released as an App. Links are below (free download): >> App Store >> Google Play |