Tydzień w gospodarce

Category: Trendy gospodarcze

In almost all developed countries, statistical data confirm the existence of wage differences between men and women (read more) . In 2016, the wage gap, that is the percentage difference between the average remuneration of men and women, amounted to 7.2 per cent in Poland and was one of the lowest in the EU, where the average gap was 16.2 per cent. The biggest gap is in Estonia, Czech Republic, Germany and the United Kingdom.

We should keep in mind, however, that these figures show the percentage difference between the average wage of a working man and the average wage of a working woman, and do not take into account any labor market characteristics. The differences in wages are due to many reasons — some women may be less educated, may have shorter track record (seniority) in the labor market, or may work in occupations that require lower qualifications or involve less responsibility. In such cases the pay gap between men and women is justified and is not a manifestation of wage discrimination.

The situation is different when women and men receive different remuneration in spite of similar characteristics relevant from the point of view of the labor market, such as: education, seniority, age, profession or even the size of the company in which they work. A question then arises regarding the cause of this phenomenon. In economic theory, there are several possible answers to this question.

One of the reasons is the phenomenon of occupational segregation of women and men. The so-called horizontal segregation occurs when employees of one sex dominate in a certain group of professions. In the economy we can observe the division of certain professions into ones that are predominantly “masculine” and ones that are predominantly “feminine”. Women’s professional activity is concentrated in a smaller number of employment areas than the professional activity of men. This is caused, among other things, by the fact, that while men have access to practically all existing occupations, women face certain limitations. In Poland, they result primarily from the Regulation of the Council of Ministers (from 1996) on the list of jobs which are particularly arduous or harmful to women’s health.

This regulation covers jobs associated with increased physical effort, performed in conditions of increased noise and vibrations, as well as underground work and high-altitude work. Due to natural biological characteristics women also rarely choose professions involving a lot of physical effort. However, cultural determinants and stereotypes concerning femininity and masculinity also strongly influence the choice of professions (read more). Thus, when large percentages of women choose typically “female” professions, the greater competition between them for the given jobs may translate into relatively lower salaries than in less crowded “male” occupations.

Women’s lower average wages may also result from the so-called vertical segregation. It occurs when, despite a comparable level of education, the percentage of women holding managerial positions is significantly lower. A situation where women’s access to managerial positions is hindered by employers is referred to as the “glass ceiling”. However, a lower percentage of women in managerial positions may also be the result of their own decisions. Due to the desire to reconcile work and raising children, some women prefer to occupy lower positions, which carry less responsibility and are therefore paid less. For the same reason, women often choose positions in the public sector which pay less but provide more stable employment.

The fact that some women choose to work part-time usually results from the need to provide care for the children or family members requiring constant assistance. Although part-time employment is not very popular in Poland, women opt for this form of employment more frequently. In 2016, among all employed women, 10.4 per cent worked part-time. For men, this share reached only 4.4 per cent. Women more frequently look for part-time work or for employment in occupations that make it easier for them to reconcile family and professional responsibilities, which is often associated with the necessity of accepting lower wages. Moreover, women’s work associated with caring for a child or a dependent person is not valuated by the labor market and is treated as a break in employment. This hampers women’s access to certain occupations or positions and means that women may have less professional experience than men whose other characteristics (such as age or education) are comparable.

However, when people with the same abilities, education, professional experience and the same ability to work are treated differently in terms of wages despite equal commitment, we are dealing with wage discrimination. It occurs when people with the same characteristics, relevant from the point of view of the labor market, are treated differently in terms of wages. According to the definition of work put forth by Kenneth Arrow, discrimination is any behavior that leads to the valuation of employees based on characteristics that are unrelated to their productivity.

Economic theory lists various reasons for discrimination against women in the labor market. Among the most notable concepts we include Garry Becker’s theory of discrimination, which indicates the different levels of investment in the accumulation of human capital in men and women as the cause of discrimination. The theory of statistical discrimination formulated by Arrow also plays an important role in the study of inequality in the labor market. According to that theory, employees are assessed on the basis of the average features of the group to which they belong and not their actual competences.

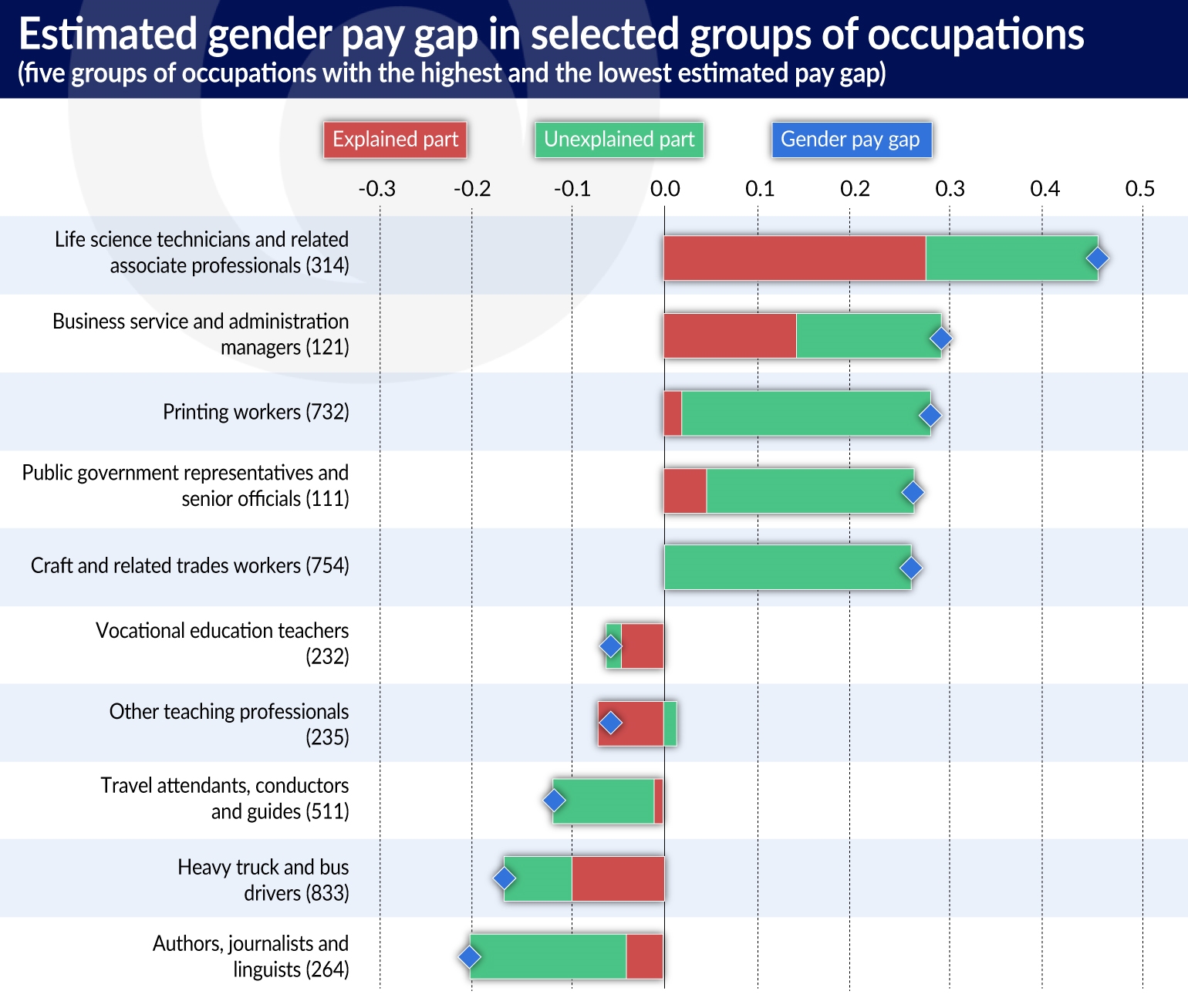

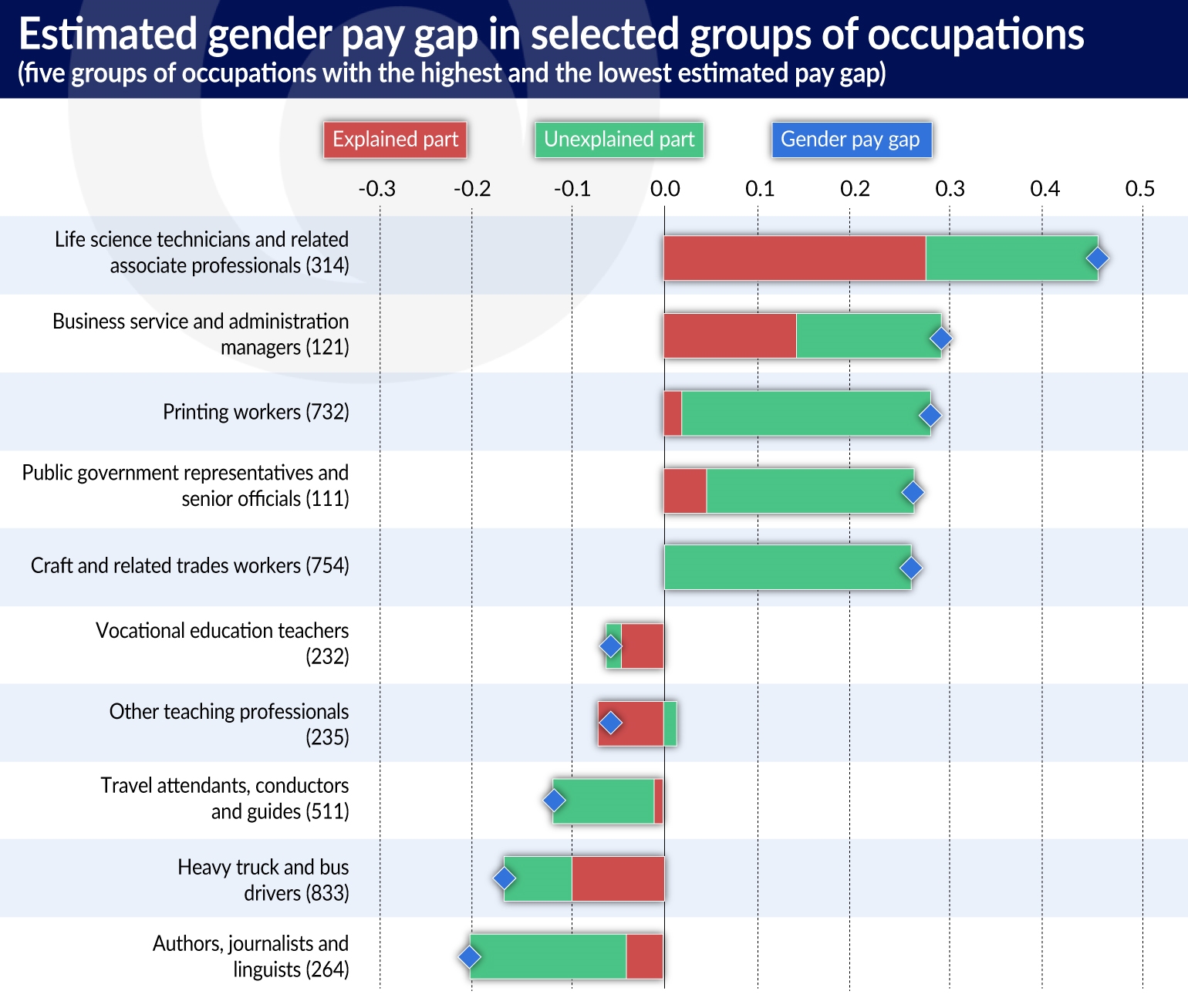

The assessment of the actual differences between the wages of women and men, that is the gender pay gap, is usually carried out with the use of the Oaxaki-Blinder decomposition, a standard econometric method designed for the purpose of studying wage discrimination. According to this method, the gender pay gap can be represented as the sum of two components. The first component shows the extent to which the differences in average wages of women and men are the result of their different characteristics: level of education, age, seniority etc. This is the so-called explained part of the pay gap. The remaining component is the unexplained part of the gender pay gap, often equated with wage discrimination in the literature. However, such an interpretation may lead to an overestimation of the phenomenon of discrimination, because at least some of the unexplained wage differences may simply be the result of factors that are not included in the model.

The empirical analyses attempt to answer a question to what extent the observed differences in the wages of women and men are the result of their different characteristics (different education, seniority, age, different workplace, occupation, etc.), and to what extent they are the result of wage discrimination? The findings of research carried out by Paweł Strawiński, Aleksandra Majchrowska and Paulina Broniatowska indicate that the differences in the wages of women and men in Poland are highly varied across the individual professional groups. The authors conducted a study of the wage gap in Poland in a cross-section of professional groups at 3-digit level in 2012. The studies were conducted on individual data from the Structure of wages and salaries by occupations report published every two years by the Statistics Poland (GUS).

The results of the analyses showed that in most of the surveyed 98 occupational groups the average hourly gross pay rate for women was lower than for men, and that the observed differences in wages of women and men are statistically significant. In addition, in as many as 13 groups, these differences were greater than 20 percent. More than half of them are occupational groups associated with managerial positions or positions of highly trained professionals, as well as the positions of skilled workers.

In the first case, a part of the wage gap is explained by the different characteristics of women and men. Some of the unexplained differences may stem from the fact that women who want to reconcile work and family life are willing to spend fewer hours working and are also less likely to work overtime. If they have younger children, they also have less opportunity to participate in foreign training courses that enhance their career development opportunities. In the case of the second type of professional groups (positions of skilled workers), wage inequality is not explained by the model, but it may be the result of variables that have not been included in it, such as physical differences.

In ten occupational groups women’s average wages were significantly higher than men’s ones. The results of the analyses show that at least in some of these groups this is explained by the significantly different characteristics of women. The negative pay gap among truck and bus drivers is particularly interesting.

One of the hypotheses that may explain its occurrence is the higher earnings of drivers working in the public sector compared with the private sector. Although women rarely find employment as drivers, most of them choose to work in the public sector, which may be associated with the growing employment of women as public transport drivers.

The authors attempted to answer the question as to whether there is a relationship between the unexplained part of the gender pay gap and the degree of masculinization (or feminization) of the professional groups, i.e. the percentage of men (or women) working in them. The objective of the study was to check whether the unexplained differences in wages are higher in occupations in which mostly men (or mostly women) are employed. The study showed that the lowest values of the unexplained wage gap (or, if we assume that all the relevant factors were included in the model, the lowest levels of discrimination) are observed in highly feminized occupations (where the percentage of women among the employees is at least 90 per cent) and in so-called balanced occupations, i.e. ones with a similar share of men and women among the employees.

The largest unexplained differences in wages were recorded in the professional groups in which the majority of employees were men. These were mainly occupations from the seventh and eighth occupational groups (industrial workers and craftsmen, as well as operators and assemblers of machines and devices). However, taking into account the nature of the jobs in these groups (these are occupations requiring physical strength), at least some of these unexplained differences in wages are probably not due to discrimination but rather to other factors that were not included in the study, such as the differences in the psychological and physical characteristics of women and men, as well as cultural determinants, such as traditions or habits. We should keep them in mind while interpreting the so-called raw statistical data and we should not assume that any difference between the wages of a woman and a man results from discrimination.

Paulina Broniatowska is a doctoral student at the Warsaw School of Economics. Aleksandra Majchrowska, PhD, is an assistant professor at the Department of Macroeconomics, Faculty of Economics and Sociology, the University of Łódź. This article was written as a result of the research project no. 2015/19/B/HS4/03231 financed by the National Science Center.