Tydzień w gospodarce

Category: Trendy gospodarcze

(infographics Dariusz Gąszczyk)

According to OECD data, 12.5% of the Polish workforce is unionised. However, in May 2013 a survey by the CBOS polling company indicated that that only one in 20 Poles belong to a union, or one in 10 employed people.

According to Polish law, a union can be set up if at least 10 workers want to join. In 2012, the Supreme Court ruled that the employer is not allowed to demand a full list of trade union members, since it would violate the provisions on personal data protection. The number of trade union members may be verified by the State Labour Inspection, which, however, has no database on trade unions.

Not only a company’s employees may join trade unions, but also its pensioners and workers on temporary contracts. Moreover, employees can belong to more than one union. This is the case in some coal mines; as a result trade union membership can exceed 100%.

The majority of trade union organisations belong to three confederations: OPZZ (All-Poland Alliance of Trade Unions), NSZZ “S” (NSZZ “Solidarity” trade unions) and the Trade Union Forum (FZZ). However, there are also thousands of trade unions not associated in any confederation. According to union specialists , several hundred thousand employees may belong to such organisations.

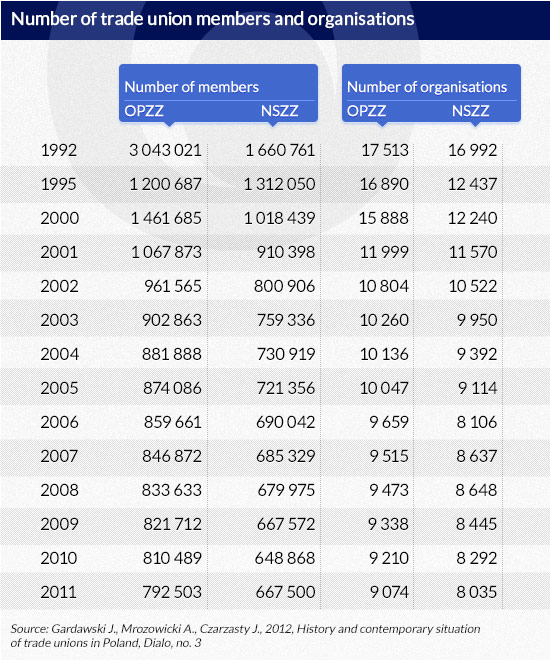

The number of trade union members is cited by the largest confederations. But it is impossible to establish how reliable these figures are. Despite their interest in inflating numbers, data from the confederations shows the number of union members is falling steadily.

According to CBOS, the average trade union member is 45 years old and works in a state-owned company or a public. The highest percentage of union members can be found in education, science, health care and administration as well as transport and communication, with a slightly lower percentage in industry. Trade unions rarely operate in private companies created from scratch. The strongest trade unions are found in state-owned companies or partially privatised companies. Sectors with the lowest trade union membership include trade and retail sales, financial services, hotels and construction as well as small manufacturing enterprises.

A CBOS survey conducted in 2014 shows 74% of respondents do not recognise any positive impact of unions on the situation of employees (38% of respondents asked about the effectiveness of trade unions responded, “They make an effort but they are not very successful”, and an additional 36 % said, “No effects of their activity are visible”).

It is worth remembering that small and medium-sized companies – where unions are almost non-existent – employ approximately 70% of the Polish workforce and generate 67% of the country’s GDP. The importance of this sector for the generation of national income is many times higher than that of mining, metallurgy or the fuel industry, where unions are stronger.

The number of trade unions is decreasing around the world – the result of broader trends. The power of trade unions grew alongside industrial development. In the United States industry overtook agriculture in terms of employment levels in 1915. The number of jobs in industry grew until the mid-1950s. Afterwards, the share of industry in the workforce started to decline. In Western Europe this process started a decade later. According to the Boston Consulting Group, the value of industrial output in the USA in the years 1973-2013 doubled in real terms, but employment in the manufacturing industry decreased by one-third, due to a leap in labour productivity. The same trend can be observed in other countries. Employees are moving mainly to the service sector, where the level of unionisation is lower than in large industrial plants. Flexible work patterns are more and more common, as well as work on-line. That makes it difficult to establish a union and difficult for an existing union to be very useful.

Various labour models exist worldwide. In the past, union membership was almost automatic in Scandinavian countries, but the number of union members is decreasing there too, although it still exceeds 50%. The percentage of unionised employees in France is surprisingly low. However, trade union membership does not reflect the intensity of employee conflicts and trade unions’ political influence. The power and political activity of French unions is greater than that of their Scandinavian counterparts, which have developed the model of dialogue with their employers. In Sweden, approximately 650 collective labour agreements apply to wages and working conditions.

In Sweden. about 90% of employment relationships are regulated under collective agreements, instead of the generally applicable labour law. Accordingly, the labour market is more flexible (it is easier to lay off and hire employees), consequently, unemployment is lower. Polish unions resemble the French ones. The level of membership is low, most issues related to employment relationships and the minimum wage are regulated at a statutory level, rather than under collective labour agreements, but unions are politically powerful. This is a result of both Poland’s historical legacy and from the concentration of trade unions in large companies, where a strike quickly become a national event.

Polish unionsare regulated by the Act on Trade Unions of 23 May 1991 (as amended). Besides its mandate to represent employee interests, the Act confers numerous privileges on unions.

U may conduct economic activity, taking advantage of tax exemptions applicable to associations. Trade unionists can also use the enterprise they are employed in for private business. In the former “Ursus” tractor factory, trade unionists established a company that used the equipment of the parent company to make spare parts for tractors. These were readily sold, while at the same time there were few buyers for finished tractors.

In the Jastrzębska Spółka Węglowa coal miner, wives of union activists ran shops on mine premises. In the Gdańsk Shipyard, the local Solidarity union held a fund-raiser by selling so-called ‘bricks’. Many union members act as insurance agents selling policies in their own plants. In companies in which the State Treasury has a stake, participation of trade union activists in supervisory boards is the rule.

Under Polish law, an employer cannot fire a member of the management board or the audit committee without union approval. As well, employers cannot amend the contract of such employees – a status that also applies to the founding committee of a new over a period of 6 months after its establishment. That means in big companies it is common practice to establish new unions when the company announces redundancies. That allows many workers to take shelter under the label “trade union activist”.

The provision exempting activists in larger trade unions from the obligation to work is particularly important for union members. When a union has fewer than members, one leder is partly exempted from woprk . If the union has from 150 to 500 members, the leader is fully released from work, while keeping existing wages, including bonuses and privileges. The number of union jobs rises along with growth in members – one additional full-time position is allocated for each thousand union members.

This regulation is the main reason for trade union proliferation. If 1500 members belong to a union , the union gets three full-time positions paid by the employer. However, if 10 trade unions are created, with 150 members each, they have 10 full-time positions and, additionally, many activists are protected against redundancy. Because workers can belong to more than one union, 1500 workers may create not just 10, but even more organisations, all with full-time positions paid by the employer.

When the Act on Trade Unions was being passed, the issue of limiting the number of activists’ terms of office of was raised. Union activists managed to block this provision and, consequently many have kept their posts since the early 1990s. “Trade union activists are true professionals,” says Maciej Grelowski, who has sat on the Tripartite Commission representing employers on behalf of the Business Centre Club. “They are always perfectly prepared for the negotiations. They know the statistics, the law, the tricks of negotiation. The representatives of the government are like blind kittens next to them.”

Union activists know their position depends on how much they achieve for their ‘clients’ – the employees. They demand high payment for their services.

Three years ago, the Treasury Ministry analysed the costs of trade union activity in enterprises at the request of the Polish Confederation of Private Employers – Lewiatan. The annual maintenance of trade unions in companies in which the State Treasury has a stake costs over 50m zlotys. In the Tauron group and KGHM it is over 10m zlotys, in the Energa group – over 5m zlotys

What is interesting is that trade union confederations do not have data concerning the number of professional activists.

“We are not entitled to collect such information.” says the press secretary of the All-Poland Alliance of Trade Unions. “Trade unions included in our confederation are independent and they do not submit financial statements to us.”

Individual unions also do not disclose their financial situation.

“The National Commission of NSZZ Solidarity employs approximately 100 people. I am unable to answer your question concerning the number of Solidarity activists in plants and their wages due to the lack of sufficient data or the confidential nature of such information,” responds the spokesperson of Piotr Duda, the head of Solidarity.

As a result, the Polish labour market is divided into two groups. The first comprises those who work in small- and medium-sized private companies or those who are self-employed, experiencing the advantages and disadvantages of the free market on a daily basis.

On the other side, there are employees of huge state-owned or partly privatised companies where the investor has concluded an agreement with trade unions and a social package was a part of the privatisation agreement. In such companies, trade unions play an important role in the decision-making process. Compliance with the Labour Code is the minimum expected by trade union activists. Employees often have privileges going far beyond the provisions of the Code. For example, in Jastrzębie Coal Mining Company, sickness benefits amount to 100% of their pay, and a recent attempt to curtail that privilege helped unleash a strike.

This division is obviously unfair. “Unprotected Poland” works harder, longer and usually has a lower income. One of the reasons for such a situation is that “protected Poland” gains a bigger slice of the national cake than it has generated.

This pathology is the result of the flawed Act on Trade Unions, which might have fit the situation in the first years of the transformation, but is currently jeopardising the restructuring of distressed large enterprises. It also offers unjustified privileges to a small group of activists.

The following changes are necessary:

1. Raising the minimum number of trade union members required to register a trade union organisation to 15; however, they should constitute at least 10%of employees.

2. Ban on multiple union membership.

3. Public disclosure of information concerning trade union finance and the obligation to have such information audited by independent auditing companies.

4. Limiting the number of unions in a single plant to the two with the highest number of members.

5. Ban on conducting economic activity by trade unions or running business by trade union activists on plant premises.

6. Self-financing of trade unions – of both full-time activists and the maintenance of office premises.

7. Financial sanctions to be imposed on the trade union and its activists for generating losses as a result of an illegal strike or other forms of protests.

8. Loss of immunity by trade union activists violating the provisions related to collective bargaining.

Many Polish union activists understand that excessive claims against an employer in difficulty could actually hurt workers. However, the current state of union law forces even moderate union leaders to strengthen their rhetoric. This was clearly visible in the case of the coal mines.