The European Commission assesses the progress of the individual countries in fixing their public finances and sets the medium-term budgetary objectives (MTO) together with the member states. The Fiscal Pact, which entered into force on January 2013 and covered all the EU Member States, with the exception of the United Kingdom and the Czech Republic, was bound to provide an additional boost to fiscal discipline. It was supposed to enforce a faster restoration of fiscal balance and prompter debt reduction.

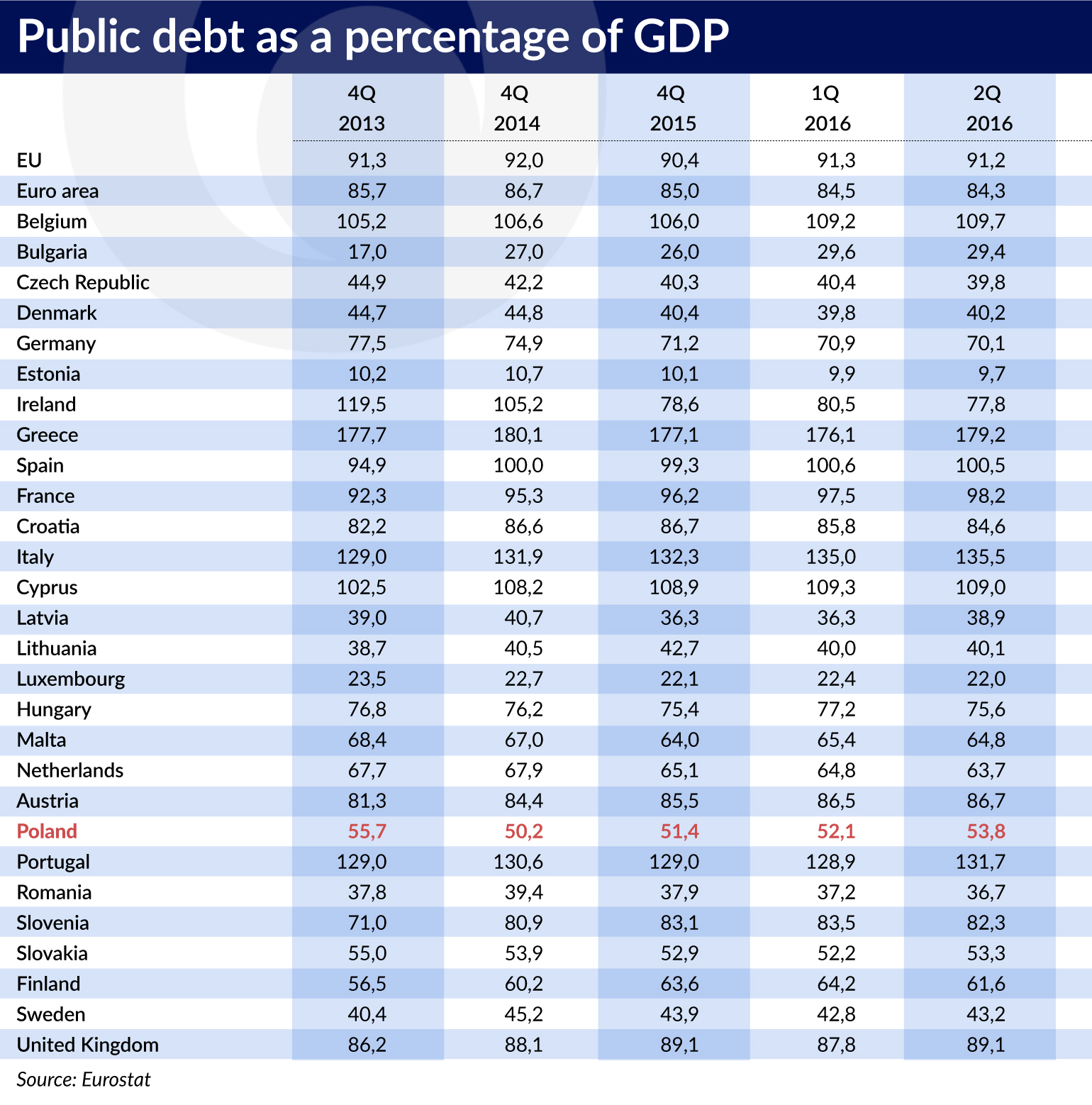

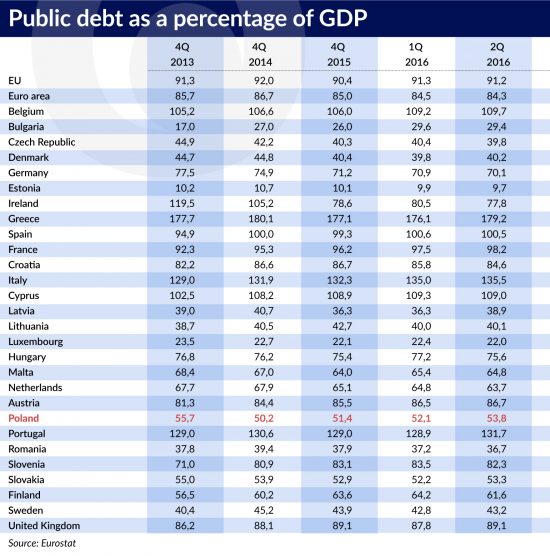

Deleveraging is taking place in the countries of Northern Europe. Impressive progress has been achieved in Ireland, and to a lesser extent in Germany, the Czech Republic, Denmark and the Netherlands. In other countries the public debt has either remained at the same level or increased over the past three years. This applies in particular to the most indebted countries: Belgium, Spain, France, Italy, Portugal and Slovenia. The level of government debt of the entire Eurozone Union has increased from 60.7 per cent in 2008 to 85 per cent in 2015. In this period the level of debt in the Eurozone has increased from 68.6 per cent to 90.4 per cent, in France from 68 per cent to 96.2 per cent, in Italy from 99.8 per cent to 131.9 per cent, in Spain from 39.4 per cent to 99.8 per cent, in Portugal from 69.2 per cent to 129.0 per cent, and in Slovenia from 21.8 to 81.1 per cent.

The European Commission, which demanded that member states take vigorous corrective actions after the financial crisis, has softened its position. Both the Stability and Growth Pact and the Fiscal Pact provide for penalties for breaking the targets agreed upon with the Union. However, the EU authorities are not using these tools and the countries with budget problems (France, Portugal, Italy and Spain) have repeatedly obtained the European Commission’s consent to the prolongation of the corrective measures. This is due to concerns that stronger fiscal tightening could result in the growth of radical sentiments in countries whose economies have been on the brink of recession for many years.

Overly optimistic report

The change in the EU bodies’ attitude towards fiscal problems can be seen in the document entitled „Implementation of the Stability and Growth Pact” of November 2016, drawn up by the European Parliament on the basis of the decisions and recommendations of the European Commission. It contains no threats of disciplinary measures against countries that do not fulfil the targets, and even the countries with a rising level of debt received a positive evaluation.

According to the document five countries in the Eurozone have a fiscal situation in compliance with the Stability and Growth Pact: Germany, Estonia, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Slovakia. The situation of another five countries has been deemed as „broadly compliant with the Stability and Growth Pact”: France, Ireland, Latvia, Malta and Austria. The eight remaining countries are „at risk of non-compliance with the Stability and Growth Pact”. These include Belgium, Cyprus, Spain, Italy, Lithuania, Portugal, Slovenia and Finland.

In comparison with the previous year the situation has deteriorated in Belgium, Slovenia and Finland, and improved in Austria. The category of „broad compliance with the Stability and Growth Pact” is a semantic trick typical of the EU.

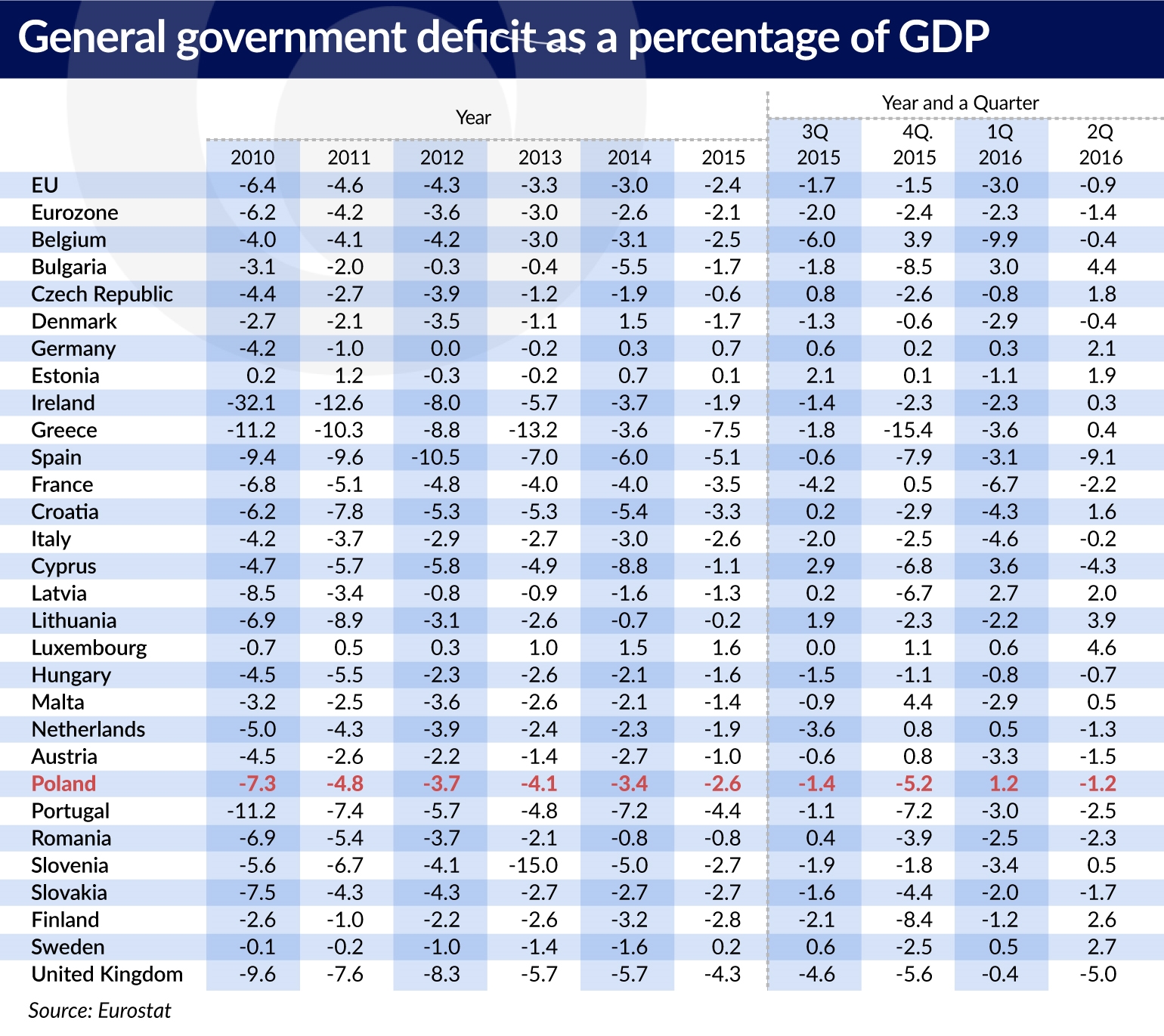

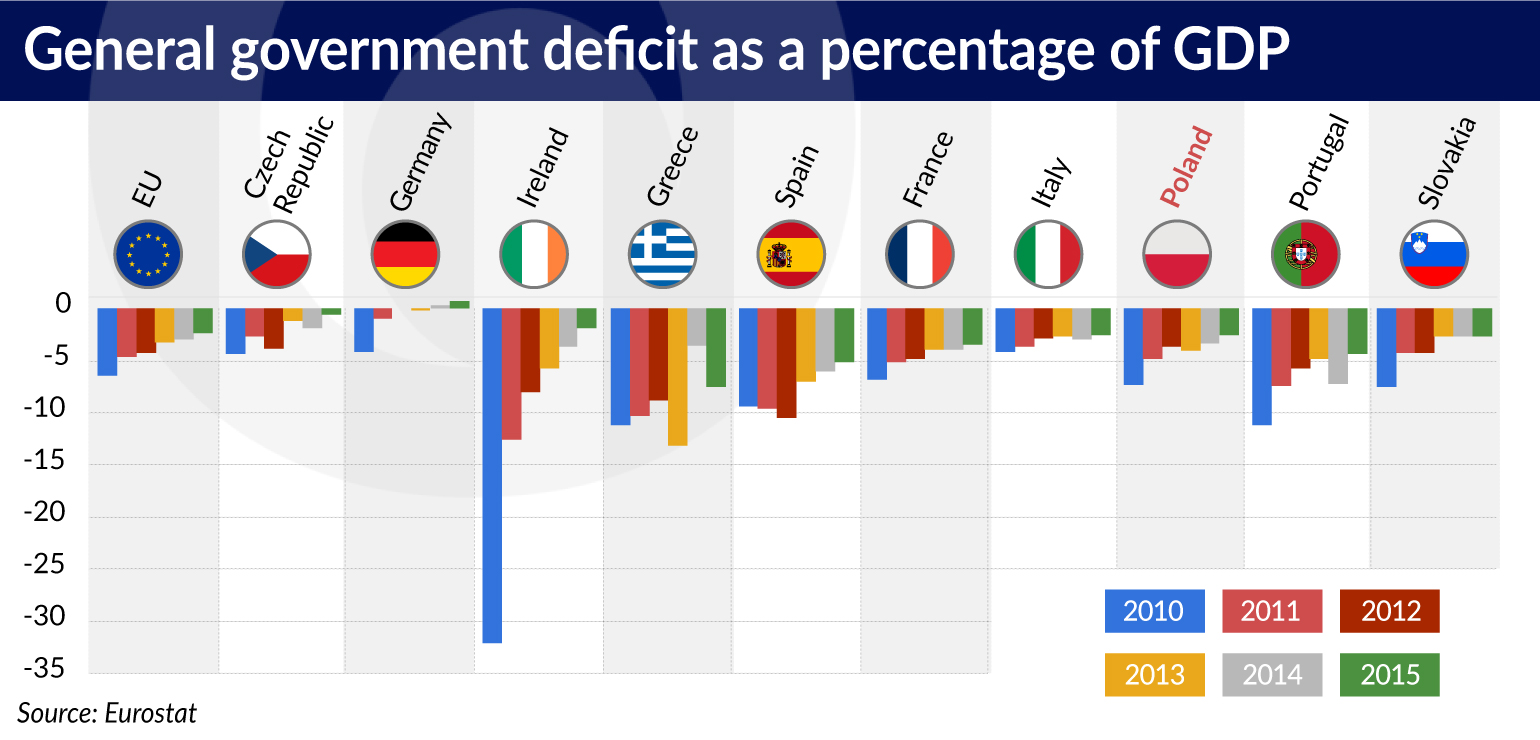

From 2010 to 2015, the European Union as a whole reduced the fiscal deficit by 4 percentage points, and the euro zone reduced the fiscal deficit by 4.1 percentage points. In most EU states the process of fiscal tightening is also taking place in the current year. Currently the following countries are in the Excessive Deficit Procedure: Greece, Spain, France, Portugal, the United Kingdom and Croatia.

The situation could become particularly difficult in three countries: France, Italy and Spain, which are, respectively, the third, fourth and fifth largest economies in the European Union.

What is worth mentioning is the improvement in the situation of the most indebted country of the European Union – Greece, which achieved a small budget surplus in the second quarter of 2016. According to the European Commission in 2017 Greece’s deficit could fall to -1 per cent and the country will record a primary surplus, which will allow it to gradually pay back its debt.

Poland in the middle range

Between 2010 and 2015 Poland has reduced the deficit of the general government sector by 4.7 percentage points. Eight countries boasted better results in this respect. But since 2012 Poland has made little progress in balancing the budget. The spring 2016 Convergence Program does not provide for the achievement of the Medium-Term Budgetary Objective – a structural deficit of 1 per cent – before 2019. According to the European Council Recommendations of 13 June 2016, there is a risk that Poland will not fulfil its obligations under the Stability and Growth Pact in the current year and in the next year. This does not necessarily mean that the current deficit level of 3 per cent GDP will be exceeded, which would result in the reintroduction of the Excessive Deficit Procedure, only just withdrawn on 19 June 2015.

Like in other European Union countries, the fiscal situation in Poland could deteriorate rapidly in the event of another wave of crisis, e.g. caused by the situation of the Italian banks.

The risk of stagnation and political upheaval

Six countries of the European Union have public debt exceeding 100 per cent of their GDP. This group should also include France, whose debt has exceeded 98 per cent of the GDP in mid-2016. Of course the debt-to-GDP ratio of 60 per cent, required in the Maastricht Treaty, and even the level of 100 per cent are arbitrarily established limits. If they are exceeded this does not necessarily mean that a given country has entered a debt spiral – that is a situation, when the debt servicing cost exceeds the capacity of the budget and the economy.

However, high debt is usually accompanied by economic stagnation, which makes debt reduction more difficult amid low inflation or deflation. A clear example of this is Greece, which decreased the fiscal deficit by 7.7 percentage points in the years 2009-2015, and whose fiscal tightening in the year 2016 will probably reach 5 percentage points, but whose debt reduction will likely only start from the year 2017. The main reason is the constant decline in GDP lasting from 2009 to 2016 (with a short break in 2014).

Greece is under special supervision of the European Union and the IMF. It can count on subsequent tranches of financing from the assistance fund, and perhaps also on partial debt forgiveness. Other countries with a high level of public debt cannot count on that.